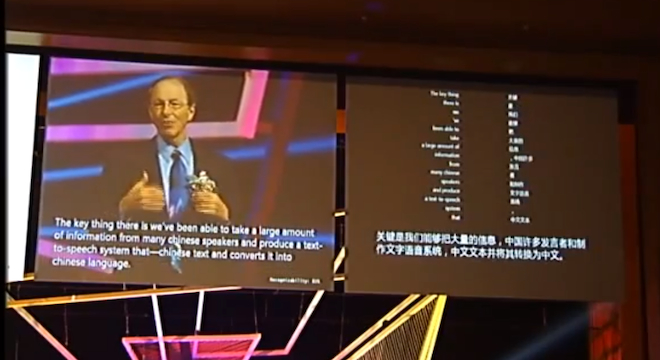

Microsoft has developed an automated speech translation system that is capable of converting an English speaker’s words to Mandarin Chinese audio in the speaker’s voice, in real time, as Microsoft’s chief research officer Rick Rashid demonstrated in a conference in Tianjin, China in late October, a video of which was posted on YouTube Thursday.

Microsoft’s simultaneous translation system, which is still just an unreleased experiment for now, is a combination of several disparate technologies built around the same type of basic speech-recognition computing principles that power all sorts of automated answering machines in use in customer service lines throughout the world today. Microsoft’s own Kinect for XBox 360 peripheral contains one of these speech recognition interfaces which allows users to issue commands and control their games by simply speaking to the device.

Microsoft’s new system, though, compiles data from many different Mandarin speakers to create a discrete Mandarin text-to-speech program. For Rashid’s demonstration, Microsoft then recorded “an hour or so,” of Rashid’s own voice and used it to customize the output voice for the speech program. Microsoft combined the audio sample with machine translation developed for Microsoft’s Bing Translator, which involves word-for-word translation and reordering of English words to make them read appropriately in Mandarin.

Check out the stunning results for yourself in the video posted by Microsoft Research (text-to-speech portion begins at 6:22):

As Rashid explained in his presentation, the system is built upon work from Microsoft researchers in collaboration with other researchers at the University of Toronto and Carnegie Mellon University.

Specifically, Microsoft and Toronto researchers decided to try and improve speech recognition rates by mimicking the human brain’s deep neural networks, improving the rate of recognition by 30 percent.

“That’s the difference between going to from 20 to 25 percent errors, or about one error every four or five words, to roughly 15 percent or slightly less errors — roughly one out of every seven words or perhaps one out of every eight,” said Rashid. “It’s still not perfect, there’s still a long way to go.”

Rashid elaborated on the development of the system in a post published on Microsoft’s Next blog on Thursday.

“In other words, we may not have to wait until the 22nd century for a usable equivalent of Star Trek’s universal translator, and we can also hope that as barriers to understanding language are removed, barriers to understanding each other might also be removed,” Rashid wrote. “The cheers from the crowd of 2000 mostly Chinese students, and the commentary that’s grown on China’s social media forums ever since, suggests a growing community of budding computer scientists who feel the same way.”

(H/T: The Next Web, Christopher Mims)

Correction: This article originally incorrectly spelled Mandarin as “Mandardin” and the city of Tianjin as “Tiajin” in one instance each. We have since corrected the two typographical errors in copy and regret making them.