The July discovery of particle decay consistent with the Higgs boson — the long missing “God Particle” — was hailed as a landmark moment in the field of particle physics, with some calling it one of the greatest scientific advances of the century.

So it was something of a surprise that the Nobel Prize in Physics of 2012, announced Tuesday, went not to the scientific consortium that led the hunt for the Higgs — the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) — but rather two completely unrelated physicists, American David J. Wineland and Frenchman Serge Haroche, for their independent work in pioneering methods to observe quantum interactions without destroying them.

Still, if members of CERN were disappointed that they didn’t win the Nobel Prize this time around, they’re certainly not showing it.

“The announcement of the Nobel prize in physics is always a great day for physics, and our congratulations go to the winners,” said James Gillies, head of CERN’s communications group, in a statement emailed to TPM. “Each year, it puts a different area of physics in the spotlight, which is great for the field as a whole.”

Specifically, the Nobel Prize in Physics 2012 winners specialized in the field of “quantum optics,” which refers to the intersections and interactions of light, that is, photons, with quantum mechanics.

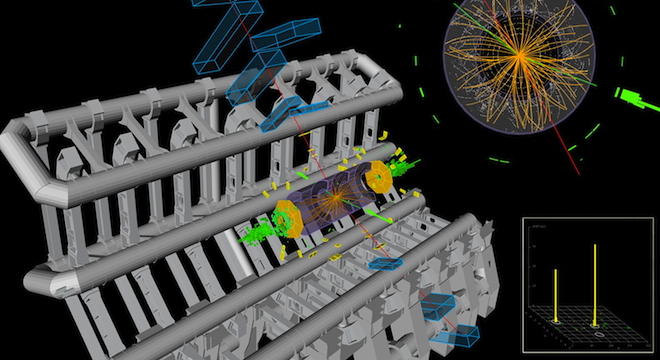

By contrast, CERN is using the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) — the world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator, nicknamed the “Big Bang Machine” — to perform experiments in the field of high-energy physics, the study of the fundamental building blocks of the physical universe.

“These are two very different things,” said Pauline Gagnon, a physicist working on the LHC’s ATLAS experiment, in an email to TPM.

Gagnon further said the methodologies that won the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physics “sounds like a very interesting achievement, which I knew very little about.”

Part of the reason that the Nobel committee likely didn’t award CERN the Nobel Prize in Physics this year is due to the freshness of the discovery of particle decay consistent with Higgs. CERN still needs to complete much more extensive analysis to say with absolute confidence that what resulted when it collided two high-energy beams of protons together at near light speed in the the Large Hadron Collider accelerator was, in fact, the missing Higgs particle (the Higgs was first theorized in the 1960s as the particle manifestation of a field that imparts all matter with mass under the widely-accepted Standard Model, which to date, contains no sufficient explanation of how mass is generated without Higgs).

“We have not yet confirmed beyond any doubt the new discovered boson is the Higgs boson,” Gagnon explained. “Can you imagine what the committee would look like a year from now if we were not to confirm that it is the Higgs boson and they were to award the prize for its discovery? It is simply premature. Next year, yes, I’ll bet on it but not until we have confirmed all its properties (which could easily take another 6 months).”

“We were not expecting the Nobel prize in physics to come to CERN this year, or even to the theorists who postulated what we now call the Higgs mechanism back in the 1960s,” Gillies further added to TPM. “The announcement from CERN concerned the discovery of a new boson consistent with the Higgs, we are still working to positively identify this particle, and would have been surprised if the Nobel committee had decided to award the prize to the theorists involved while this work is ongoing.”

Still, if and when CERN wins a Nobel Prize for its Higgs boson work, actually deciding who the award will go to remains a problem as well, considering the fact that the Large Hadron Collider experiments involve an international collaboration of around 10,000 scientists.

“As far as the experiments are concerned, the Nobel prize is shared by a maximum of three people, and it is difficult to see how three could be chosen from the thousands involved in the LHC project,” Gillies pointed out.

“The committee could choose the spokesperson of the experiments but even then, who should it be?” asked Gagnon, proceeding to propose a number of eligible names:

“For ATLAS, should it be Peter Jenni who was there during the designing and construction phase for 20 years or to Fabiola Gianotti who was in the lead for 4 years when we collected data? Same for the other collaboration, CMS. So it becomes impossible to give it to the right person. Then symbolically, it could be given to CERN Director General, Rolf Heuer, but even that would not be optimum. Lyn Evans, who oversaw the construction and implementation of the LHC, the 27-km long accelerator, was also another person whose name was circulating lately. In my opinion, the prize should go to the theorists, François Englert and Peter Higgs for their far-reaching foresight. We would not have looked for it if they had not predicted it.”

The Large Hadron Collider recently completed its first collisions involving lead ions and protons, and is due to undergo a long, nearly year-long shutdown beginning in February 2013 while its equipment is upgraded to run at even higher energies. During that time, analysis of the data gathered from the experiments that produced the results consistent with Higgs will proceed.