The U.S. Federal Trade Commission is facing the fact that facial recognition technology is becoming more commonplace in commercial settings and on Monday released new guidelines (PDF) for companies that use the technology, what it calls “best practices.”

The FTC notes that the new guidelines “are not intended to serve as a template for law enforcement actions or regulations under laws currently enforced by the FTC,” but adds that “[i]f a company uses facial recognition technologies in a manner that is unfair under this definition [section 15 of the U.S. Code, subsection 45 a], or that constitutes a deceptive act or practice, the Commission can bring an enforcement action.” In other words, it may fine a company or impose other terms in a settlement, such as when the FTC fined Google in August for violating consumer privacy and settled with Facebook in November 2011 over other consumer privacy violations.

Some of the guidelines the FTC offers seem like no-brainers: Don’t put facial recognition technology “in sensitive areas, such as bathrooms, locker rooms, health care facilities, or places where children congregate,” for example.

But beyond that, the FTC wants companies using facial recognition to build their apps and services with “privacy by design,” securing any biometric information captured of customers/users from unauthorized “scraping” by third parties.

The FTC also advises companies to delete any photos or other information captured of consumers using facial recognition once a consumer deletes his or her account on a website, such as those that allow users to virtually “try on” eyeglasses.

Interactive signs and ads that use facial recognition technology should have clear, large-enough warnings to alert consumers before they approach the area where the technology is in use.

There are two cases where the FTC believes that companies need to get a consumer’s “affirmative express consent,” that is, an “opt-in,” before using information captured via facial recognition: When identifying anonymous individuals to third parties that wouldn’t otherwise know who they were, and when using any data or imagery captured via facial recognition for purposes outside of what was initially stated by the company.

In case companies weren’t already aware, the FTC also points out that what’s okay under U.S. law concerning facial recognition technologies might be illegal in other countries.

As the FTC’s report states: “…In other countries and jurisdictions, such as the European Union, in certain circumstances, consumers may need to be notified and give their consent before a company can legally use facial recognition technologies”

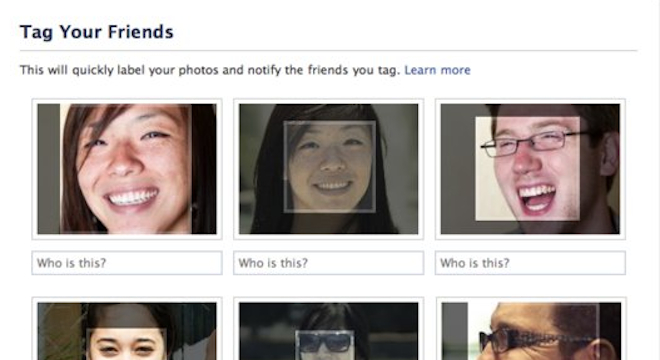

That’s the entire basis of the German data protection authority’s decision to reopen its own investigation of Facebook in August over Facebook’s use of facial recognition technology in Facebook’s automatic photo-tagging suggestions feature.

The FTC begins its report by referring to the seminal Philip K. Dick story turned Hollywood movie “Minority Report.”

In the 2002 film Minority Report, Steven Spielberg imagined a world in which companies use biometric technology to identify us and serve us targeted ads. Ten years later, that vision is coming closer to reality. Having overcome the high costs and poor accuracy that once stunted its growth, one form of biometric technology – facial recognition – is quickly moving out of the realm of science fiction and into the commercial marketplace.

The FTC goes on to state that facial recognition software’s accuracy has improved drastically in the past 20 years, with the “false reject rate,” when a computer erroneously detects a match between two different peoples’ faces, halving every two years between 1993 and 2010 at which point the error rate was below 1 percent.

As far as how facial recognition is currently being implemented, the FTC cites the company SceneTap as an example, pointing to SceneTap’s ability to survey the faces of crowd members at night clubs to “determine the demographics of the clientele,” including age and gender.

Interestingly, not all of the FTC commissioners were in favor of releasing the new facial recognition guideliens for U.S. companies: Commissioner J. Thomas Rosch, who has a history of issuing dissenting opinions to the rest of the 5-member commission (he penned what the New York Times called a “blistering” dissent to the Facebook settlement, saying that allowing the company to walk away without admitting fault undermined the FTC’s authority, yet also came out against the “Do Not Track” browser standard that would allow consumers to preemptively block targeted online ads) had his dissent attached to the FTC’s facial recognition report.

Rosch’s objections stemmed from three different points: 1.) That the FTC was incorrect to bring up consumer “unfairness” standards as a reason that companies should follow the guidelines (Rosch thinks that the “deception” standards are alone reasons enough) 2.) Facial recognition hasn’t been misused yet so the FTC shouldn’t be telling companies what to do or what not to do.

As Rosch puts it:

“There is nothing to establish that this misconduct has occurred or even that it is likely to occur in the near future. It is at least premature for anyone, much less the Commission, to suggest to businesses that they should adopt as ‘best practices’ safeguards that may be costly and inefficient against misconduct that may never occur.”

3.) Rosch thinks that the Commission shouldn’t be asking companies to provide consumers with options for how facial recognition technology is used, stating that “it is difficult, if not impossible, to reliably determine ‘consumers’ expectations’ in any particular circumstance.”

Still, it appears that overall, the Commission believes that facial recognition technology is on the verge of becoming pervasive, and companies better be aware how they use it lest they want the agency on their tails.