Sorry, “Star Wars” fans: Luke Skywalker’s twin star homeworld of Tatooine has got nothing on a newly discovered planet that exists in a quadruple star system, found in part by the crowdsourced science website Planet Hunters, an effort that enlists “citizen scientists” to help sift through astronomical data.

The planet, which has been designated “PH1” in honor of it being the first such extrasolar planet spotted through the Planet Hunters website, is a burning hot gas giant slightly larger than Neptune, about six times the radius of Earth and located some 3,200 light years from our home planet.

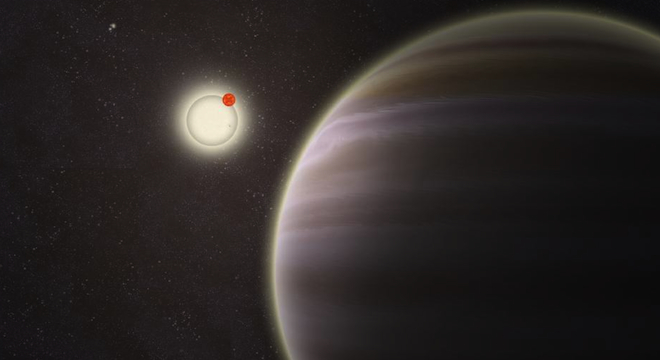

Most remarkably, PH1 not only orbits two stars in what’s known as a circumbinary system, but those two stars are themselves orbited by two other stars located far away, some 900 times the distance from the Earth to the Sun, according to NASA.

Although PH1 is not located in its the habitable zone — a distance relative to its stars where liquid water could form on the planet — the view from the planet would include a fascinating four-star sky.

“All four would be visible,” wrote Chris Lintott, an astrophysicist at Oxford University and an author on a scientific paper describing the find, in an email to TPM. “The two more distant ones might each be as bright as the Moon was on Earth.”

PH1 was spotted first by two users of the Planet Hunters website combing through the mounds of data captured by NASA’s Kepler spacecraft, a photometer, or light meter telescope, launched into orbit above Earth in March 2009, specifically designed to hunt for Earthlike, habitable planets around other stars based on “light curves,” brightness measurements from those stars that may dip if a foreign object, such as a planet, crosses in front of them.

However, the Kepler mission produces an enormous volume of data, capturing brightness of 150,000 new stars every 30 minutes, on Kepler’s quest to survey the region of the Milky Way Galaxy around Earth.

Planet Hunters, an offshoot of the citizen science website Zooniverse, believes that human volunteers may be better equipped to sort through the numerous “light curves” than computer algorithms, “because of the outstanding pattern recognition of the human brain.”

Two citizen scientist members of Planet Hunters, Robert Gagliano and Kian Jek, first caught dips in the brightness around the star system that they thought could be evidence of a planet, and they brought their findings to the attention of Megan Schwamb, an astronomer at Yale who also works on Planet Hunters.

Schwamb then assembled a team of 10 experts to go over the observations and verify they were evidence of a planet, and rule out false positives.

“With the mass limit and the radius we estimate for the planet, we can confirm that the orbiting body must be a planet and not a star,” Schwamb wrote to TPM in email.

The Kepler mission has already confirmed 77 extrasolar planets, including one in the habitable zone and other circumbinary (Tatooine-like) planets in distant star systems.

PH1 is the first planet to be found in a system with four stars, a gravitational environment that until now was thought to be far too intense for planet formation to occur.

“We think that planets form from a disk of leftover material around young stars, but we would have expected that disk to be disrupted by the presence of the other stars,” Lintott told TPM. “We will need to go back to the models and see if we can explain what’s happened, because right now it doesn’t make a huge amount of sense.”

As other scientists involved in the discovery point out, the planet’s existence likely means that the further out of the two stars didn’t impact how it formed.

“The presence of the planet suggests that the pairs of stars never came very close together because a close encounter would have likely destroyed the disk of material that forming planets would have come from,” added Schwamb, in an email to TPM.

That said, the planet likely does endure weird conditions as a result of its placement — suspended between four stars.

Light and heat, for instance “will change as the planet and stars swing around their orbits,” Lintott wrote to TPM. “It must have some pretty strange seasons!”

Other than its radius and mass, and the fact that it is a gas giant in a four-star system, scientists don’t know much else about it, though they are eagerly reviewing Kepler’s data for any more information they can glean.

“More spectral observations of the host stars PH1 will help us constrain the age of of the planetary system which we estimate as approximately two billion years,” Schwamb wrote. “Additionally we might be able to get spectroscopy of the two companion stars in the future and better know what their temperatures and composition are.”

The researchers have submitted their paper for review to The Astrophysical Journal, but a pre-review copy is available for free online here.

Aside from challenging our conception of the universe and prior astronomical frameworks, the find also marks an important indication of crowdsourcing’s potential in contributing to research.

“At the start of 1995, no one had found a planet around a normal star, and now this is something anyone can do with a bit of luck and a web browser,” Lintott said. “It’s also important that Kian and Robert organised themselves to look at such interesting systems, showing that citizen scientists, as we call them, can do really quite advanced tasks and still produce useful results. “