Scientists have for the first time pinpointed what they believe to be starless galaxies, also known as dark galaxies — gas-filled clusters without much light that are theorized to have been important features of the early universe, leading to the development of the multitude of bright, star filled galaxies that now populate the Universe.

The discovery of 12 distinct dark galaxies located some 11 billion light years from Earth, announced Wednesday, was achieved using the Very Large Telescope (VLT), a series of visible-light and infrared telescope instruments located in the mountains of northern Chile which are managed by the European Southern Observatory.

A trio of scientists, one based out of Switzerland, another the UK and the third California, found the dark galaxies — which are extremely difficult to detect as a result of their low light emissions — by using one of the most brilliantly lit objects in the known Universe: a quasar, or a distant galaxy with a supermassive black hole at its center, which spits out energy and light as it sucks in the stars and matter around it.

“It was one of the most exciting moment of my research career so far,” wrote Sebastiano Cantalupo, a scientist at the University of California Santa Cruz and lead author of a paper on the findings, in an email to TPM.

Specifically, Cantalupo and his colleagues were able to use the VLT to detect the 12 dark galaxies because the hydrogen gas that comprises them emitted a tell-tale glow when bombarded with the ultraviolet light from the nearby quasar HE 0109-3518.

“This is one of the most luminous quasars in the Universe,” Cantalupo explained to TPM. “It is so powerful (more than one hundred trillion times the Sun) as to illuminate every dark galaxy over huge distances around it, more than 10 million light years. Such a large volume increased our chances to detect these elusive objects.”

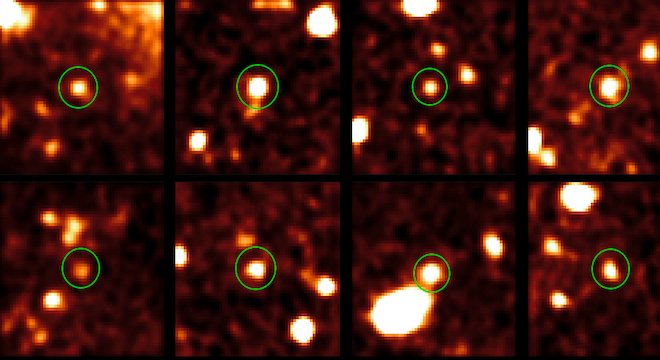

The 12 dark galaxies can be seen in the following ESO image as indicated by the artificially-added blue circle markings. The red circle in the middle indicates the quasar.

Locating these dark galaxies is a hugely important step toward understanding the formation of the present Universe, because they are thought to be the building blocks of more fully-fledged galaxies, like our own Milky Way.

“We can imagine the dark galaxies as ‘infant’ galaxies in a early stage of their evolution when the properties of the gas (like its composition, density or some still unknown parameter) are not ideal to form stars,” Cantalupo explained.

“We still do not have a definitive picture on the way in which stars form out of the primordial gas. It is possible that these galaxies remain dark until they become massive enough to ignite efficient star formation. Recent theoretical models have suggested that small galaxies in the Early Universe might remain ‘dark’ until they grow enough or when they collide with each other. In our current picture of galaxy formation, big galaxies might acquire a large fraction of their gas through ‘cannibalism’ of smaller systems.”

Cantalupo said that such collisions were likely how our own Milky Way formed. Rewinding and removing all the stars from the dense regions of our galaxy, would be able to see a dark galaxy.

Dark galaxies have long been theorized but not conclusively found until now, although a cloud of hydrogen spotted earlier in 2007 by the Hubble Space Telescope may be a potential candidate as well.

The method of using an external light source, like the quasar used in this case, has also been in discussion for some time, since 1996, but again, the actual practical implementation of such a method remained elusive.

Cantalupo himself acknowledged the “very long hunt,” for the dark galaxies.

“In our first attempt in 2007 we detected several candidates but given the very experimental nature of the method, the results were not completely satisfactory,” Cantalupo told TPM. “In 2010 we changed our strategy, building our own optical filter and learning from previous experience. A careful and detailed data analysis required 1 year and half before we were finally able to announce our exciting results.”