The world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator is no match for the moon.

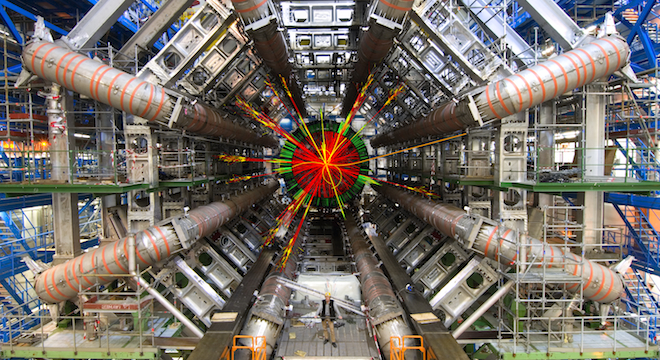

That’s the observation of one of the scientists working on it, Dr. Pauline Gagnon, a physics professor at the University of Indiana Bloomington, who recently posted a blog entry describing a spatial surprise she encountered last weekend while running one of the six major ongoing experiments at the Large Hadron Collider, a 17-mile-around underground accelerator located near Geneva, Switzerland, which has been nicknamed the “Big Bang machine,” because it is designed to simulate the conditions of the early universe.

As Gagnon recalled it, everything seemed to be going smoothly until the end of her shift, when another scientist called in to report unexpected fluctuations in the data coming from the planned collisions of two high-energy proton beams taking place in the accelerator. Take a look at the following graph to see the fluctuations, represented as dips.

Gagnon wrote in her post:

So I called the LHC control room to find out what was happening. “Oh, those dips?”, casually answered the operator on shift. “That’s because the moon is nearly full and I periodically have to adjust the proton beam orbits.”

Here’s what was going on: The moon’s own gravitational field was pulling more strongly one side of the Large Hadron Collider, every-so slightly deforming the tunnel through which the proton beams pass.

The deformation also changed as the Moon rose and fell in the night sky. In order to keep the proton beams on track, the operator at the LHC’s control center had to subtly alter the direction of the proton beams to accomodate the Moon’s pull, “every hour or two,” Gagnon explained in an email to TPM.

As Gagnon wrote in her blog post:

“Since the moon’s effect is very small, only large bodies like oceans feel its effect in the form of tides. But the LHC is such a sensitive apparatus, it can detect the minute deformations created by the small differences in the gravitational force across its diameter. The effect is of course largest when the moon is full.”

The reason for the full moon having the most pronounced effect on the LHC is due to the fact that at that point in the lunar cycle, both the gravity of the Moon and the Sun are pulling on Earth along the same axis, the same combined effect that causes dramatic sea tides.

Gagnon told TPM that the pull of the Moon could be enough to disrupt the LHC’s experiments, if it weren’t for the operators’ careful attention.

“I could be a concern if the operators did not know what to do,” Gagnon said. “But clearly, they do since they kept these beams for 23 hours.”

As Ganon further noted: “The effect was first observed 25 years ago,” in another, weaker particle accelerator, the LEP, which was decommissioned in 2000.

But, as Gagnon told TPM: “I do not recall seeing it so vividly on a graph before when I worked on LEP. Maybe I was never on shift when the moon was full! “