NASA’s unmanned Voyager 1 spacecraft is due to make history soon, when it becomes the first spacecraft to leave our Solar System and enter interstellar space, ahead of its sibling Voyager 2, which is still about two billion miles behind.

Scientists aren’t sure when that day will come, but it should be soon — within months or possibly a few years, a relatively short time given the spacecraft’s 35-year life so far.

Voyager 1 survived massive doses of radiation near Jupiter in 1979 and last fall encountered strange, unexpected phenomena at the Solar System’s outer reaches, an area known as the heliosheath, where the particles from the Sun begin to drop-off and particles from the galaxy begin to filter in. The entire Solar System is, in fact, encased in a massive bubble of solar particles known as the heliosphere.

Voyager 1 is about to break free of that bubble and fly straight into the cold, dark, unexplored regions separating our own Solar System from the rest of the star systems and other planets in the Milky Way Galaxy, humanity’s first ambassador to the stars, a gold-plated record of Earth sounds and images in tow.

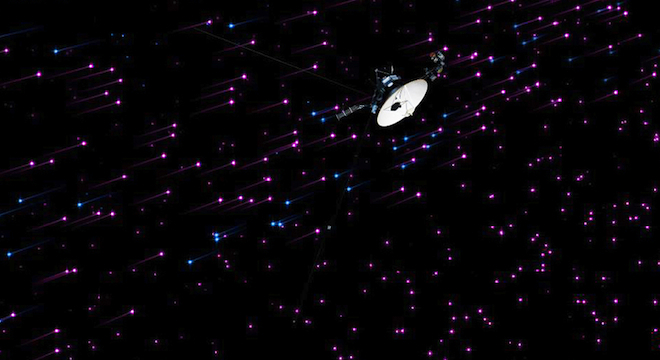

Here’s a NASA video animation showing the new region that Voyager 1 has entered, where low-energy particles from the Sun (purple) begin to escape out into space and galactic cosmic ray particles (blue) begin to stream in:

Whenever the day comes, Voyager’s entry into interstellar space will be bittersweet, as it will also mark the beginning of the end of the spacecraft’s nuclear-powered life. The plutonium-238 battery that powers Voyager 1 is running out, and starting in 2020, NASA will have to begin shutting off its five remaining functional instruments one-by-one in order to conserve enough power to keep the other instruments going and Voyager beaming back data to Earth till 2025, when power will be out for good. That’s no small order, given that at 11 billion miles out from the Sun, it takes Voyager’s radio signal 17 hours to return to Earth.

But NASA isn’t sure yet exactly in what order it will shut off Voyager 1’s five still-functioning instruments, according to Voyager project scientist Edward Stone, in a phone interview with TPM.

“We don’t have a plan,” Stone told TPM. “What we decide will depend on the state of the instruments when we begin to shut them off, what we’ve learned from them and what we think we can continue to learn.”

Stone is a renowned, 76-year-old physicist at Caltech who designed the spacecraft and has been in charge of it and its sibling Voyager 2 since before their launches in 1977.

Here’s a NASA video illustration of the two spacecraft’s journeys throughout the Solar System:

The five remaining instruments NASA has to choose from to deactivate include: The Magnometer, a magnetic field measuring instrument; the Low-Energy Charged Particle instrument (LCEP), for measuring levels of low-energy particles; the Cosmic Ray Sub-system (CRS) for measuring levels of cosmic rays, including high and low-energy electrons; the Plasma Wave Subsystem (PWS) for measuring plasma waves and low-frequency terahertz radiation waves; and a UV spectrometer for measuring ultraviolet radiation and the “backscattering of Sunlight” as Stone explained to TPM.

Stone said that the UV spectrometer, which failed on Voyager 2, would likely be the next instrument turned off on its further-ahead sibling.

As for what Stone expects to learn from the remaining instruments once the Voyager 1 spacecraft leaves the Solar System, the scientist told TPM he and his colleagues will be looking for several key indicators of what the interstellar environment is like, but are open to surprises.

“We make models but we don’t know the conditions well enough to be able to accurately predict what were going to be able see,” Stone said.

The models project an “interstellar wind” outside the heliosphere, but Voyager 1 is expected to provide the first measurements of the speed of the neutral atoms that make up some of this wind, as the neutral atoms cannot enter the Solar System.

Stone added that Voyager should be able to give scientists the first detections of how many slower cosmic rays exist outside the Solar System. Slower also being relative in this case — about 40 percent the speed-of-light, according to Stone.

“We know that the heliosphere forms a barrier to prevent the entry of somewhat slower cosmic rays from outside,” Stone explained. “But how many are out there? Is it a large number? Is it a small number? We just don’t know.”

Here’s a NASA illustration of the heliosphere:

Another measurements Voyager 1 can provide is on the interactions of “blast waves,” the mass of charged particles that are released during coronal mass ejections from the sun (often associated with solar flares), and the cosmic rays at the edge of the solar system.

As for what any hypothetical human astronauts traveling to these outer regions of the Solar System might expect to encounter, Stone said it was a good thing that Voyager 1 was unmanned.

“One of limitations of being in deep space is that further out you go the higher the radiation level is,” Stone said. “Cosmic rays in particular, they have particles like X-rays, that can create problems for living organisms.”

Given the unusual and unforeseen conditions Voyager 1 has encountered so far at the edge of the solar system — including a “magnetic highway” where the Sun’s magnetic lines are somehow connecting to those in interstellar space, despite running perpendicularly to each other — Stone is preparing for more of the unseen.

“I’m sure well get some surprises,” Stone said.

Here’s a NASA video of Stone explaining the “magnetic highway” phenomena, published December 3:

Correction: This article originally incorrectly identified the Voyager record as “gold-played,” a misspelling of “gold-plated.” We apologize for the error and have since corrected it in copy.