Slim Chance

As a young chemist, Tony Wood faced a tough dilemma after completing his post-doctoral research. Should he pursue a career in academia or pharmaceutical research?

While academia had many attractions, the dream of one day producing a medicine that would improve patients’ lives was so inspiring that he decided to join Pfizer in Sandwich, England. There he was soon to lead the Antiviral Chemistry Group, with the goal of creating innovative, life-saving drugs. Wood met with his retiring predecessor and realized achieving his goal wasn’t going to be easy. For scientists, the odds of making a medicine that can ultimately be prescribed are less than one in a thousand.

“I remember sitting in his office feeling like my career was already finished as he told me virals is a tough area and that I’d never discover a medicine,” Wood says. “I remember thinking at the time, ‘This is not going to be the case; I’m determined to find a medicine here.’”

Epidemic Proportions

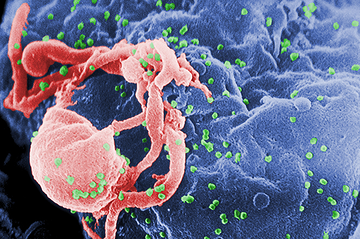

This was at a time when HIV related deaths were at an all-time high. In 1995, AIDS was the leading cause of death among Americans aged 25 to 44. Though there were some treatment options available, many patients were developing resistance to them, or struggling with horrible side effects. The need for additional treatment options could not be more urgent or immense. It was the epidemic of the 90’s.

New Discoveries

At the time, it was known that HIV infection happens when the virus enters a T cell through a molecule, or “receptor,” called CD4. But researchers in New York City, Boston, and Bethesda discovered that the virus must also bind to one of two other co-receptors, named CCR5 and CXCR4, in order to enter the cell. For 80% of newly infected patients – half a million at that time in the US – it’s through the CCR5 co-receptor. Scientists also discovered that some Caucasians inherit genetically defective CCR5 genes from their parents, which make their cells highly resistant to HIV infection.

A Small Start

Wood and his small team in Sandwich, England experimented with the revolutionary idea to target the co-receptor, as opposed to the virus. In their lab, they started investing energy and resources, but for months their research was fruitless. The team kept finding compounds that bound to the co-receptor, but they didn’t seem to stop the virus from entering the cell. Was their research strategy flawed?

Roadblocks

After a year of research, they invented a compound that had an anti-viral effect and they were feeling positive. But it wasn’t long until they learned that the compound had the potential to cause deadly cardiac toxicity. They were back to the drawing board. Wood describes this period as: “We’d solve a problem, identify a new one, solve a problem, and identify a new one.” In the area of drug discovery, determination and stamina are essential qualities.

The Right Compound

After months of hard work, the team finally found a game-changing compound that blocked the virus from entering the cell and did not have the potential for cardiac toxicity at projected antiviral doses. With this discovery, the drug was ready to enter pre-clinical trials. They all knew there was a very long journey ahead. Success would mean years of clinical trials and tens of millions of R&D investment dollars. However, they also knew the probability of the compound meeting all the safety and efficacy requirements for a medicine meant the chance of success was limited.

A Major Breakthrough

The compound entered small clinical trials in 2001 ramping up to more than 130 clinical trials over the next six years. Wood was keeping a close watch on his discovery: “The drug was almost like our child for us,” he said.

By 2004, 40% of treated AIDS patients had moderate to severe resistance to available AIDS treatments. At Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, all 18 patients on the study responded well, and the virus was diminishing in their body in as little as two weeks. Doctors reported being able to tell that patients were improving just by looking at them.

“There were anecdotes about patients who were preparing to die, but they were put on SELZENTRY and it transformed them and they were returning to their lives,” Wood said.

Approval

More than 10 years after he and his team first started working on SELZENTRY, the medicine was granted FDA approval in 2007. It was the first oral HIV medication in a new drug class on the market in over a decade, and data showed incredible results. After taking the drug for 48 weeks, nearly three times as many patients receiving SELZENTRY achieved undetectable levels of the HIV virus compared with those who didn’t take it.

Worthy Recognition

Wood and his team started receiving accolades for their work. SELZENTRY won the Scripp Award for Best New Drug and the Prix Galien “best pharmaceutical agent” award. Pfizer was even awarded for how they lowered the environmental impact of SELZENTRY during manufacturing.

Between 2006 and 2009, overall HIV incidence in the United States became relatively stable at 50,000 annual infections. While SELZENTRY was initially approved for long-term patients, in 2009 it was made available for the newly diagnosed. More important was the fundamental breakthrough that HIV/AIDS had been wrestled down into a manageable disease – a notion thought impossible just a few years earlier.

In 2010, SELZENTRY won the Discoverer’s Award, PhRMA’s highest honor, recognizing discoveries of special benefit to mankind.

Where Are We Now?

Researchers are currently working to determine if SELZENTRY is effective and safe for the one quarter of HIV positive patients in the US who are also infected with hepatitis C. The combination of these two diseases is the leading cause of chronic liver disease. Scientists are also evaluating if the drug is safe for more than 10,000 HIV positive children under the age of 13.

**

SELZENTRY is just one of many lifesaving drugs that has gone through the long and often unpredictable pharmaceutical research, development and approval process before making it to patients. Follow the graphic below to learn more about the effort that goes into making prescribable treatments and cures.