The Supreme Court on Tuesday opted to hear arguments in a case that could redefine “one person, one vote” — one of the bedrock principles of modern voting rights law. The case could change how electoral districts are drawn across the country, revamping who comprises electoral districts and reshaping the idea of who is ultimately “represented” by elected officials.

The case, Evenwel v. Abbott, originated in Texas and is being spearheaded by a conservative legal group. Legal experts tell TPM that the impact of the case could be far-reaching, especially for Latinos and residents of urban districts.

Here’s what you need to know:

The Supreme Court Could Fundamentally Change How Electoral Districts Are Drawn.

Currently, electoral districts at the federal, state, and local levels are typically drawn to divide the total population of the jurisdiction equally (or nearly equally) among comparable districts using census data. Dividing the population among equal districts using the total population figure is a cornerstone of the “one person, one vote” principle.

The challengers in the Texas case, represented by the conservative legal group Project on Fair Representation, argue that Texas’ use of total population alone is unconstitutional because it “distributes voters or potential voters in a grossly

uneven way.” Population figures include a significant number of people ineligible to vote, such as immigrants in the country illegally, felons, and young people below the minimum voting age, among others. The practice of using total population to create electoral districts means the portion of eligible voters is much higher in some districts than others, even though they have relatively similar population sizes.

The case now before the court arises from the redistricting of Texas’ state Senate districts. The challengers have not proposed an alternative method for redistricting, although, in making their argument, they did point to registered voters and citizens of voting age as points of comparison.

If the challengers to Texas’ traditionally-drawn Senate districts prevail, the case could have a much broader impact.

“It would change the way that redistricting is done virtually everywhere in the country,” said Michael Li, counsel for the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program, a non-partisan organization that defends voting rights.

Such a ruling “could be throwing states into an unmanageable situation where they don’t have the data they need to redistrict,” said Nina Perales, the vice president of litigation at the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, which had sought to intervene in the case when it was at the lower court.

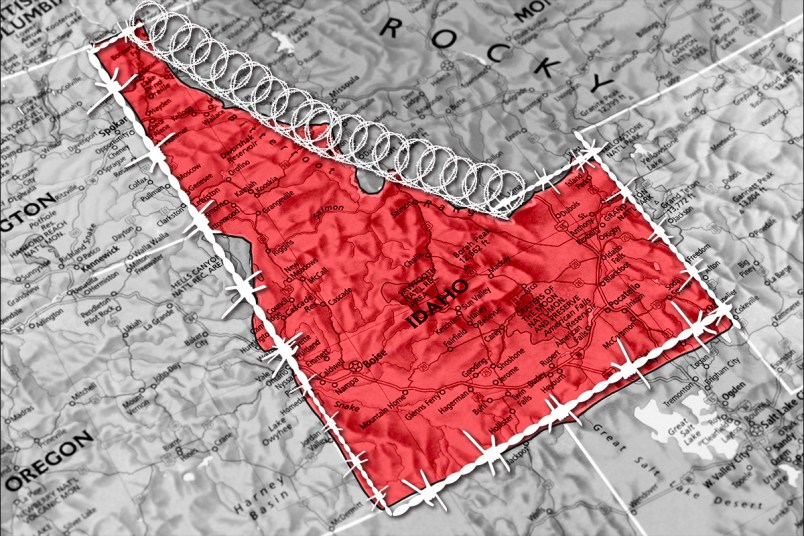

Latinos Could Be Most Affected By Redefining ‘One Person, One Vote.’

If the Supreme Court buys the challengers’ argument and decides states don’t have the discretion to use total population alone as a redistricting standard, states would also have to take into account other yet-to-be-determined metrics in drawing districts.

“What that would mean practically is that in parts of Texas where you have large numbers of noncitizens, let’s say Latino noncitizens, those districts would get diluted representation if we are looking at total population because we would be drawing districts based on numbers of voters,” said Richard Hasen, a professor at UC-Irvine School of Law who also runs the Election Law Blog. “So some districts may end up having many more people in them because the people would include the noncitizens.”

Critics say that the case is geared to weaken the electoral power of demographic blocks that tend to vote for Democrats and even the challengers highlight that urban districts tend to have a lower rate of eligible voters than rural ones.

“This is an attempt to cut back on growing Latino political strength in the state by packing Latinos into a smaller number of districts,” Perales said.

However, Latino noncitizens are not the only demographic group that could see their representation in districts shift depending on how the Supreme Court comes down. Districts that have a high population of children could also be diluted, as could those with a prison within their borders or a high volume of ex-convicted felons, who also cannot vote in some states. Depending on which metrics are used under any new legal scheme, districts where voter turnout is relatively high or low could also see their numbers affected.

‘One Person, One Vote’ Has Remained Largely Unquestioned For 50 Years — Until Now.

The decision of the court to examine the case is “kind of a surprise,” Hasen said. “It has been settled in earlier cases, we had thought, that states have discretion to decide how they put the one-person, one-vote principal into effect.”

In the 1960s, a number of federal courts addressed the issue of redistricting, as some states were not redistricting at all according to how their populations changed. In 1964, the Supreme Court established in Reynolds v. Sims that state legislative districts must have roughly similar populations, which states since have been using total population data to determine.

“This is a universal practice, there hasn’t been a lot of clamoring to change it,” Li said.

However, the Supreme Court did give Hawaii leeway to deviate from using direct population to determine districts, given the state’s unique characteristics. That case in 1966, Burns v. Richardson, plays a prominent role in the challengers’ brief, as does a partial dissent by Judge Alex Kozinski in a 1990 appeals court case, where he noted the one-person, one-vote question “deserves a more careful examination.”

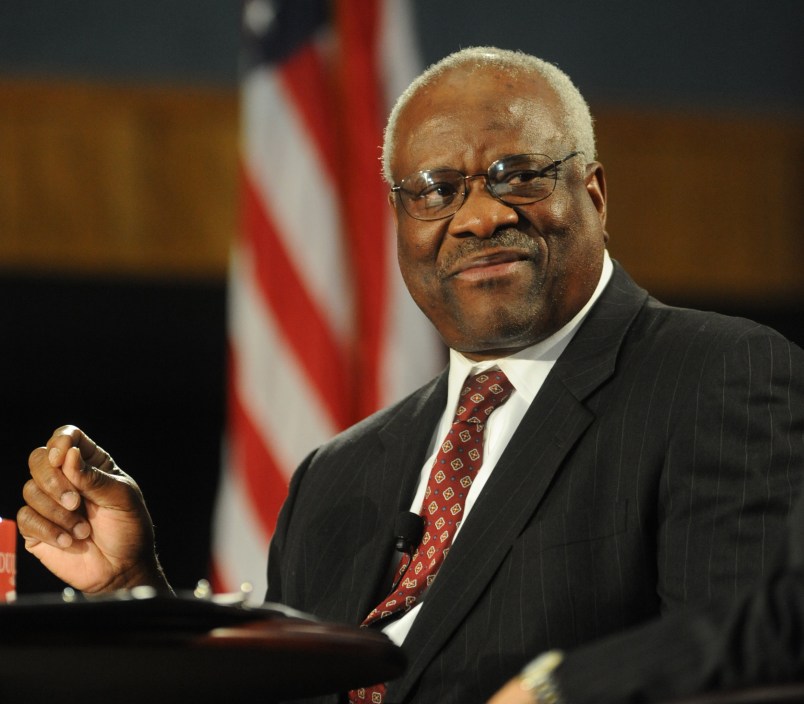

In 2001, Justice Clarence Thomas dissented from the Supreme Court’s decision not to take a case examining Houston’s districting plan, noting his own concerns about the lack of court guidance when it comes to using total population.

The Case Comes To The Supreme Court Outside The Typical Procedure.

Typically, a case is first heard at the district court level, and then in an appellate court, where it’s heard initially by a three-judge panel, then by a full panel of appeals court judges who can further weigh in on a decision that the three-judge panel makes — before it is appealed up to the Supreme Court. Evenwel v. Abbott came up to the Supreme Court through a different route, as a direct appeal of a district court decision to dismiss the challengers’ case.

At issue is whether the special district court panel that dismissed the challengers’ case was correct when it ruled that the Texas redistricting based on total population was a political question that the court did not have jurisdiction to decide.

The high court could request further briefing on the issues and is expected to hear oral arguments, but a decision on the case’s merits is not guaranteed. It could kick the case back down to the lower court for further proceedings.

“This Supreme Court may be signaling it is time to create a more national rule regarding ‘one person, one vote,’ but this is not necessarily a signal that the Supreme Court is going to overturn the current practice of using total population for ‘one person, one vote,’” Perales said.

The Conservative Group Behind The Lawsuit Has Brought A Number Of Other Voting Rights Cases.

Project on Fair Representation, the group bringing the suit, is led by Edward Blum, who has also been involved in Supreme Court cases that have attacked affirmative action policies and gutted a portion of the Voting Rights Act.

Other groups coming out in support of the challengers include the libertarian Cato Institute and Judicial Watch.

In general, Texas’ redistricting scheme has faced a number of challenges on this and other grounds, Hasen said.

“The mix of partisan politics, the rise of Latino voters in Texas and its sheer size and importance nationally, makes it a very inviting target for litigation,” Hasen said.