The CBO score released Monday on the Senate health care bill rained down what must have been the worst nightmare—or close to it—for the GOP senators squeamish about the bill: blockbuster coverage losses just about as bad as the House version’s, Medicaid provisions that kick off even more people from the program than the House bill and average premium reductions that come at the cost of making insurance inaccessible for many low income people.

Already, it appears Senate Republicans don’t have enough votes to advance the legislation, and it will be a scramble to get that number up to 50 for Senate Republicans to pass the bill, the Better Care Reconciliation Act, this week, as planned.

Lawmakers will only have a day, maybe two, to analyze the report before GOP leaders are expected to move forward with a procedural vote to advance the legislation Tuesday or Wednesday, with the goal of a final vote by the end of the week. Before the score was released, a handful of conservatives and two moderate Republicans had signaled opposition to the draft legislation, though the conservatives said they were mostly open to negotiations. About a half dozen more moderate Republicans, and particularly those from Medicaid expansion states, are in the hot seat to make up their mind about supporting the bill, and the CBO score only turns up the temperature.

Here are 5 points on how Monday’s score affects GOP leaders’ ability to find 50 votes in favor of the legislation:

The new score offers Senate GOPers nowhere to hide.

The hope that the Senate would be able to fix the House Obamacare repeal bill and make it less “mean” — to borrow the label employed by President Trump—has officially been dispelled. Twenty-two million fewer people with insurance is hardly a better headline than 23 million fewer with insurance, the score of the House’s American Health Care Act. It certainly doesn’t make the Senate bill “far superior,” as Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME), a key vote for leadership, promised before the legislation was unveiled.

Soon after the CBO released the score, Collins announced she would not support the current version of the legislation.

The Medicaid numbers look bad for moderates.

Senate moderates had hoped to cushion some the House bill’s drastic cuts to the program. The CBO said that overall the bill would result in a reduction of $772 billion in federal funding for the program over the next decade and 15 million fewer people enrolled by 2026.

Republicans from expansion states sought a slower “glide path” in phasing out in the expansion. In return, conservatives got stiffer cuts down the road for the overall program. The CBO didn’t break down how many of the Medicaid losses were due to expansion or the more general cuts, but either way, the Senate moderates appear to be the losers in the changes they made to the House’s plan. The Medicaid enrollment losses in the Senate bill, according to the CBO, are even greater than they were projected to be in the House version of the plan, where 14 million fewer people were enrolled by 2026 compared to current law.

Even the premium decreases aren’t an entirely happy story.

The No. 1 goal of conservatives in the negotiations was to lower premiums, and the topline 30 percent reduction in premiums in 2020 compared to current law that the CBO found come with a major caveat. Those reductions could come primarily in loosening ACA regulations and driving consumers to skimpier plans, the CBO found. So the lower premiums are largely just a result of shifting towards plans with higher out-of-pocket costs for consumers. For those at the lower end of the income scale, the deductibles will make insurance worthless, especially coupled a tax credit scheme in the Senate bill that is less generous than the ACA’s.

“As a result, despite being eligible for premium tax credits, few low-income people would purchase any plan, CBO and JCT estimate,” the CBO reported.

For instance, a person at 75 percent of the poverty line (making $11,400 in 2026) would pay only $300 in annual premiums but face a deductible more than half their annual income, the CBO predicted.

Rural areas are still a challenge under the Senate bill.

The Senate Republican bill doesn’t escape a problem GOP lawmakers have used to rip Obamacare, and the Senate legislation may in fact make it worse. The CBO found that a “small fraction of the population” will live in areas where no insurers would participate in the marketplace, or the participating insurers would offer “only very high premiums.”

“Some sparsely populated areas might have no nongroup insurance offered because the reductions in subsidies would lead fewer people to decide to purchase insurance—and markets with few purchasers are less profitable for insurers. Insurance covering certain services would become more expensive—in some cases, extremely expensive—in some areas because the scope of the EHBs would be narrowed through waivers affecting close to half the population, CBO and JCT expect.”

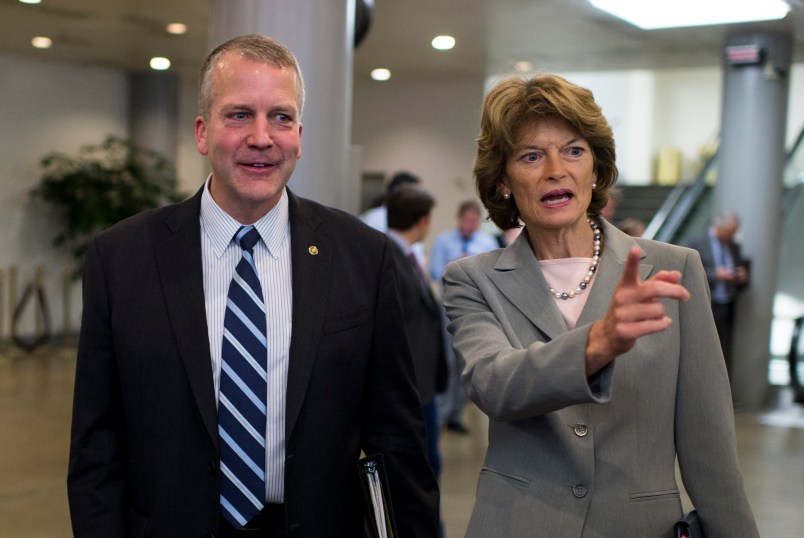

The Senate bill doesn’t grapple with the underlying issues that make rural regions low-competitive areas for insurers, and the less generous tax credits stand to only exacerbate the problem. This section should catch the attention of Sens. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) and Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV)— both expansion state Republicans who raised concerns about the Senate bill’s direction and who represent largely rural states.

GOP leaders have $200 billion to play with in their final round of deal-cutting.

There was one piece of good news in the CBO report for GOP Senate leaders seeking to pass the bill. The $321 billion in net government savings the CBO found the legislation would result in means that Republican leaders have $200 billion or so to play with and still hit the $119 billion savings target of the House bill that makes their legislation eligible for reconciliation.

That may provide the opportunity for leadership to figuratively buy off the votes from skeptical moderates, by funneling the extra savings into substance abuse programs or other requests moderates have made to blunt the effects of the Medicaid cuts.