Heading into last week’s election, Democrats had poured considerable resources into avoiding the Republican sweep that happened a decade ago, in the 2010 midterms, and that allowed GOP lawmakers in several states to draw legislative maps with extreme tilts to their advantage.

But Tuesday was a rough night for down-ballot Democrats, even as it gave Joe Biden the presidency. And it blunted much of the momentum that they and nonpartisan redistricting reformers had achieved in the 2018 and 2019 elections that had undercut Republicans’ gerrymandering leverage.

Because of those earlier Democratic successes, Republicans do not have quite the the level of control when it comes to drawing state and U.S. congressional seat districts that they did in 2011. But they still stand to be pretty dominant. In 2011, Republicans were able to draw, without input from Democrats, 213 congressional seats so that they were within Republicans’ total control. Next year, that number will likely be in the neighborhood of 175–180.

“The landscape [for Democrats] in a lot of ways is better than it was in 2011,” said Michael Li, a senior counsel for the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program. “But there are key hotspots, mainly in the South.”

Republicans are in a good place to wipe out the current Democratic margin in the House.

Part of the reason House Democrats were upset that their majority shrunk this year is that things are going to get worse for them in 2022, even before you take into account any midterm anti-Joe Biden political headwinds. That is because, with the click of a mouse, Republican mapmakers will be able to undo some of the benefits that Democrats have reaped in recent years from a political realignment that has shifted suburban voters in their favor.

In about 20 states, Democrats will be playing no role in the redistricting process (a few of those states have at-large districts for Congress), meaning Republicans will have full control of redrawing districts that were getting more competitive.

“Democrats were looking at probably a six or seven seat advantage in the House. Republicans can wipe that off he board immediately,” said David Daley, a journalist and author of “Ratf**ked: Why Your Vote Doesn’t Count,” a book that examined the Republican redistricting gambits of 2011.

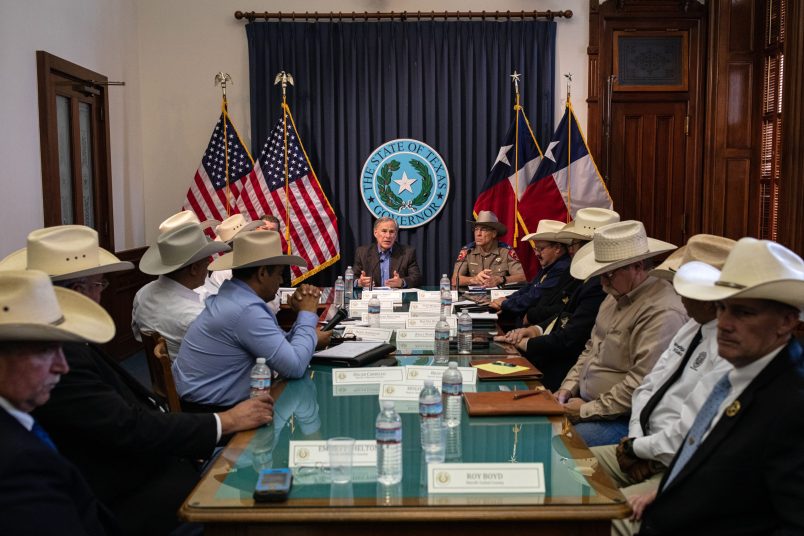

“If Republicans are able to redistrict three seats in Texas, they take back the two in North Carolina, take back one in Kansas, one in Kentucky right there, that could be the difference between control of the House in 2022, even before you get to any other states,” Daley said.

Not only did Democrats on Tuesday fall short in their efforts to flip legislative chambers from red to blue, Republicans flipped a chamber to get full GOP trifecta in New Hampshire, shutting Democrats out there. Republicans also held on to their super-majority in Kansas, which will allow them to cut Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly out of the redistricting process.

Democratic dreams in the South are likely dashed for another decade.

Where Democratic shortcomings in 2020 will be felt the most is in the South, where they have made few inroads in preventing the 2011’s redistricting fiasco from repeating itself. They failed in attempts to flip legislative chambers in North Carolina, Georgia and Texas, so they will have no seat at the table in those states when it comes to redistricting. (North Carolina has a Democratic governor, but he has no veto power over the maps.)

That means even as those states’ populations have grown in ways beneficial to Democrats — as evidenced by Biden’s showing in Georgia — Republicans will draw the maps in a way that circumvents those trends. For instance, Texas is expected to gain an additional 2–3 House seats.

“Activists and Democrats have imagined the day that Texas goes blue for a long time,” Daley said. “They thought they were close to the finish line. And by losing in 2020 it’s going to allow Republicans to stretch the finish line … perhaps for another decade.”

Furthermore, Texas, Georgia and North Carolina will not have to go through the Voting Rights Act’s process for getting federal approval of their maps, the way they did in 2011, before the Supreme Court gutted a relevant provision in the law.

But Dems aren’t nearly as screwed as they were in the 2010 cycle.

Largely because of wins Democrats put on the board in the 2018 and 2019, they’re still in a better position than they were in 2011.

In the upper Midwest in particular — which Biden’s win proved remains competitive for Democrats — they have gotten themselves a seat at the redistricting table, or at least found ways to impose some guardrails on the process.

Democrats’ 2018 win of the Wisconsin governorship — coupled with Republicans falling narrowly short on Tuesday of securing legislative supermajorities — will give Gov. Tony Evers the power to veto overly Republican maps (though there are ongoing concerns about Republican lawmakers’ attempts to short-circuit his authority). Likewise, Democrats put Tom Wolf in the Pennsylvania governor’s mansion, giving him a role to play in redistricting there.

And while Democrats will not play any direct role in Ohio’s map drawing, they’re hopeful that some modest redistricting reforms that voters approved in 2018 will withstand GOP legal affronts now that Republicans’ majority on the state Supreme Court has been shrunk from 5-2 to 4-3.

Democrats now have in place a redistricting commissions in Michigan, where the election of a Democratic judge on Tuesday flipped the state Supreme Court’s majority and put the commission on better ground for surviving attacks in court.

“We’ve broken up [GOP] control in a bunch of states that actually matter and where Democrats compete,” Patrick Rodenbush, a spokesperson for the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, told TPM.

A key question is the role other kinds of entities will be allowed to play in breaking up gerrymanders.

But the safeguards Democrats can point to even as they won’t be drawing the maps themselves have their own vulnerabilities. A case before the U.S. Supreme Court concerning Pennsylvania’s mail ballot deadline could be a signal of whether the Trump-stacked court will be inclined to overturn the precedent from a 2015 case that upheld the constitutionality of Arizona’s redistricting commission.

The dispute, driven by a controversial legal theory, is over whether the Pennsylvania state Supreme Court violated the U.S. Constitution’s Elections Clause by tweaking the state’s mail voting rules. Though the case now looks unlikely to affect the result of the presidential election, if the U.S. Supreme Court still decides to take it up, it could issue a ruling that would curb state courts’ ability to rein in partisan gerrymandering.

In addition to the gains they made on the Michigan and Ohio high courts, Democrats are hopeful that they can eke out wins in tight elections that will cement their majority on the North Carolina Supreme Court. The court’s Dem majority previously threw out an extreme GOP partisan gerrymander and could do so again.

But that tool for curbing gerrymanders — as well as the use of independent commissions to draw maps — could be at risk if the U.S. Supreme Court okays the maximalist version of the arguments that the Pennsylvania Republicans are putting forward. Even if they decline to get involved in the Pennsylvania dispute, those questions could be teed up in another case down the road.

“In the ordinary world, I would be very skeptical,” Li said, noting the Arizona precedent as well as how the Supreme Court pointed to ballot initiative redistricting reforms in a more recent ruling ending the federal judiciary’s role in policing gerrymanders.

“On the other hand, you have some justices at least seeming like you’re willing to take a really outlier interpretation of the Elections Clause,” Li said.

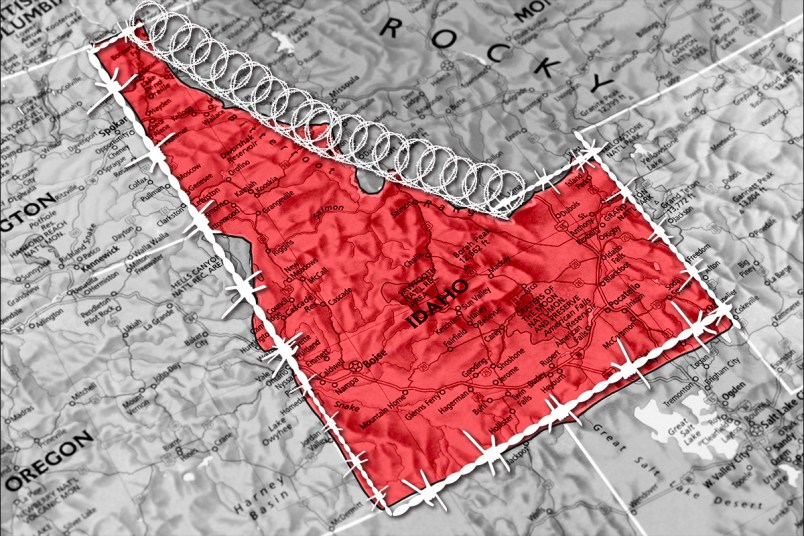

On the horizon is an even more extreme approach to gerrymandering.

Another important test on the horizon: whether states will try to draw maps based on the number of voting age citizens (known as CVAP or citizen voting age population), instead of based on total population. That change in the metric would be a fundamental shift in the philosophical underpinnings of who deserves representation. It would also favor Republicans, which is why the Trump administration has worked very hard to facilitate this overhaul by directing the Census Bureau to produce CVAP data usable for redistricting.

The incoming Biden administration could halt the release of that data, which won’t be produced until March at the earliest. But a Republican ballot initiative that narrowly passed in Missouri provides a model for how Republicans across the country can prepare for such a shift, once a granular level of citizenship data is made available (by a census conducted by a Republican administration or otherwise) for the states to implement it.

The Missouri initiative, put on the ballot by GOP legislators two years after voters approved a redistricting reform measure, also shows how such reforms can be quickly undone. It watered down the 2018 measure in technical ways that could still have big impacts.

“The fights in the next decade might be more subtle and more technical, but they’re likely to be every bit as devastating,” Daley said.