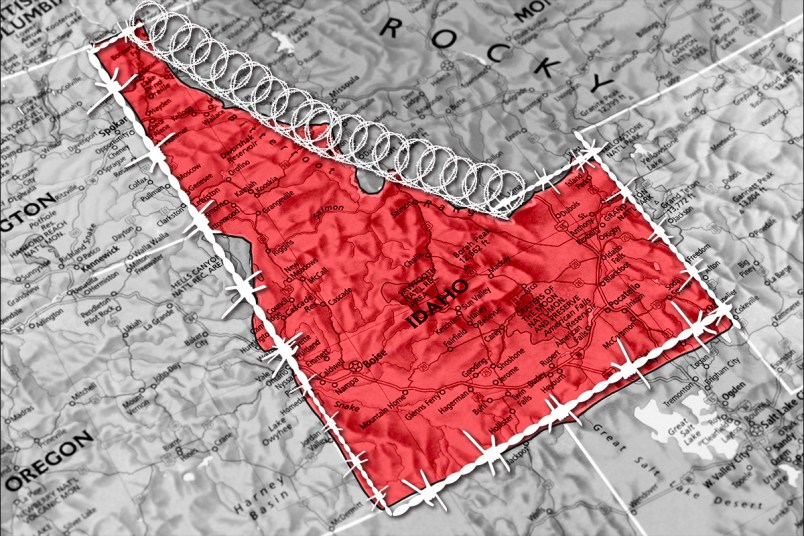

The Supreme Court has for decades avoided addressing partisan gerrymandering, concerned about about meddling too much in the inherently political process of drawing state legislative and congressional districts.

Their next chance to weigh in on the issue begins Tuesday, when oral arguments kick off in a pair of interrelated cases arguing that extreme partisan gerrymandering fatally undermines democracy.

In 2018, to the deep disappointment of voting rights activists, the court kicked cases from Wisconsin and Maryland back to the lower courts, citing standing and procedural concerns. Since then, the reform-curious Justice Anthony Kennedy has been replaced with staunchly conservative Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

But advocates for reform remain cautiously optimistic that this time, things might turn out differently.

Attorneys in two consolidated cases fighting Republican gerrymandering in North Carolina and a case challenging Democratic gerrymandering in Maryland say they will present a complementary, factually robust array of legal arguments for the court to evaluate.

The conduct on display could not be more stark. The defendants in the consolidated case Common Cause v. Rucho and in Benisek v. Lamone openly stated that they rigged maps to help their political party win, and that it worked.

Here’s why the plaintiffs think they’ll get a ruling from the court this time around—one way or the other.

The standing and procedural issues are taken care of

The court won’t be able to punt on the substantive issues presented by extreme partisan gerrymandering the way they did last year. In its June 2018 Gil v. Whitford ruling, the court ruled that the individual Wisconsin voters who brought the suit lacked standing to argue that the entire state’s legislative map was unfairly rigged to benefit the GOP. Instead, Chief Justice Roberts wrote, voters could only speak to the “district specific” harm in the way their particular district was drawn. The court kicked the case back down to a lower court to allow plaintiffs another opportunity “to prove concrete and particularized injuries” suffered as a result of the maps.

Those standing issues no longer apply.

Common Cause brought on the state Democratic Party as well as individual plaintiffs from every district in their North Carolina suit. (A three-judge panel consolidated a separate League of Women Voters’ gerrymandering lawsuit with the Common Cause suit back in 2017.)

The Maryland case is a continuation of one that the court sidestepped last year. Benisek v. Lamone ended up before the Supreme Court because of a procedural quirk, so the court sent the case back to the lower for a proper trial. The case is now back before the court after a panel of federal judges ruled that Democratic Maryland lawmakers unfairly drew a congressional district to boost their majority, and Maryland’s Democratic Attorney General filed an appeal.

The facts of the cases are crystal clear

The North Carolina case involves a congressional map drawn to ensure that Republicans could hold on to 10 of the state’s 13 seats in Congress. As State Rep. David Lewis (R), one of the chairs of the redistricting committee, infamously said during a 2016 legislative meeting: “I propose we draw a map to give a partisan advantage to 10 Republicans and three Democrats because I do not believe it’s possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and two Democrats.”

In Maryland, Democratic state lawmakers crafted a map in 2011 intended to oust a longtime GOP incumbent, giving their party seven of the state’s eight congressional seats. Former Gov. Martin O’Malley (D) acknowledged that the successful effort was intended to create “a district where the people would be more likely to elect a Democrat.”

As Michael Kimberly, the lead attorney in the Maryland case, has put it: “The facts are so stark.”

The defendants openly stated that they engaged in intentional partisan gerrymandering to give their party more control, making the constitutional issues at hand simpler to navigate.

The justices will be presented with a menu of legal arguments

The first hopeful sign for voting rights advocates was the court’s decision to schedule oral arguments in the Rucho and Benisek cases for the same day. This allows the justices to hear all the possible perspectives on what a judicially reasonable standard for determining a partisan gerrymandering might be. The justices will also see cases of both GOP and Democratic gerrymanders, driving home the point that this is something both parties engage in when given the chance.

In Maryland, the plaintiffs argue that the practice violated Republican voters’ First Amendment rights to free speech and association. Diluting Republicans’ power by intentionally changing the composition of their district prevented them, as a community of interest, from working together to secure the electoral outcome they wanted by recruiting candidates and raising funds.

The same is true in the Tar Heel State, where the congressional map splits the country’s largest historically black public college, North Carolina A&T, neatly in half, meaning students need to reregister if they’re moved from a dorm on one side of campus to the other.

The North Carolina plaintiffs are also making the case that excessive partisan gerrymandering violates the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law.

“There’s a menu of options, each of which we believe presents a reasonable and judicially manageable standard,” Allison Riggs, a North Carolina attorney working on the League of Women Voters case, said at a January conference on redistricting hosted by Common Cause. Riggs called the cases “complementary, not contradictory.”

“If any of us win, all of us win,” Riggs said.

Kavanaugh consolidated the court’s conservative majority

The attorneys in these cases are well aware that the replacement of the more moderate Kennedy with the stridently conservative Kavanaugh makes their fight harder. Kennedy was seen as the key swing vote on this issue. In 2004, he wrote that a legal standard could be developed to determine when partisan gerrymandering ran afoul of the Constitution.

As a circuit judge for the D.C. Court of Appeals, Kavanaugh never had to weigh in on any gerrymandering cases, but experts predict he will rule in line with his small government, noninterventionist worldview.

“It’s a different court,” Riggs said at the January conference “We’ll be realistic about that and how we frame our standard presented to the court.”

“We’ll be talking to [Chief Justice John] Roberts a lot as the new middle,” Riggs added.

The great fear among redistricting reform advocates is that Kavanaugh ends up as the deciding vote reversing lower court decisions that found the Maryland and North Carolina maps unconstitutional. If so, experts predict, legislatures will feel they have the green light to gerrymander maps with abandon going forward.

Court more likely to act ahead of decennial redistricting

Any sort of guidance—even a modest, narrow ruling instituting rules to stop the most extreme gerrymanders—would be a welcome win for advocates of reform. And they believe that the justices may want to take some action this time—if only to stop being asked to weigh in on the issue in case after case.

In Maryland, Attorney General Brian Frosh is urging the Supreme Court to provide clear guidance on the standards state lawmakers need to apply when they create their new maps. If the court agrees that the current maps are unconstitutional, the two states will likely have to redraw them before the 2020 election.

And the 2020 census is drawing near, followed by the next redistricting cycle that will dictate what the country’s state legislative and congressional maps will look like for the next decade. Advocates say the time for the Supreme Court to act is now.