People are voting early in this pandemic election at volumes they have never voted early before. Late last week, with 11 days still to go before Nov. 3, the number of early votes cast surpassed the total early vote in 2016.

It’s too soon to tell how much the of the early vote surge — which includes skyrocketing use of vote-by-mail, as well as a sizable increase in in-person early voting — is due to an increase in overall turnout, and how much of it is a product of the ways in which COVID-19 has affected Americans’ plans for casting ballots.

And without knowing what total turnout will be — or even the party breakdown of early voters in some states — there’s only so much speculation that can be done about the final result.

But already, looking at the data that is available, election experts are seeing some fascinating trends in who is using early voting and how they’re using it. Here are five points on the dynamics so far:

The Data Contains Both Good And Bad News For Efforts To Make Voting Safer During The Pandemic.

As the pandemic was setting in in March and April, there was major concern — validated by chaotic spring primaries — about whether voters and election officials would be able to adapt to changes necessary to make voting safer in time for the general election.

The early vote numbers suggest that voters are taking seriously the “Make A Plan” refrain that encouraged voters to consider all their various ballot-casting options, and to not wait until the last minute to decide which option they will use.

Usually, this current week is when most early voting would happen in the states that traditionally offer it, according to David Becker, the executive director of the Center for Election Innovation. But in states across the country, the number of early votes cast before this week even began has exceeded the total number of early votes cast in 2016, and in some places early voting is now even beginning to taper off.

The public messaging push to “flatten the ballot curve” appears to have been effective as well in encouraging voters to send in their mail ballots as early as they felt comfortable doing so, so to prevent election officials from being overwhelmed by a glut of ballots coming in right before the deadline.

Remarkably, even in places like Arizona and Washington — where vote-by-mail was widely used before the pandemic — voters have shifted their habits to get their ballots in sooner than usual.

But the uptick of in-person early voting has not come without problems, according to MIT political science professor Charles Stewart, who is co-directing the Stanford and MIT Healthy Elections Project. As has been captured by anecdotal news reports, those early voters are often stuck in long lines and at crowded polling places — the same thing that election experts were hoping to avoid by encouraging a shift away from in-person Election Day voting.

“It’s a known fact that people wait in lines longer during early voting than on Election Day,” Stewart said.

In some states, like Florida and Georgia, where early in-person voting was common before the pandemic, its use has trended down as more people turn to mail-in voting. But elsewhere, in places where use of in-person early voting has increased, “it actually could be more dangerous for public health,” Stewart said.

How People Are Voting Early Is Scrambling The Usual Partisan Breakdowns.

The volume of early ballots being cast is larger than ever. But consistent with previous elections is that Democrats are doing the bulk of early voting and we should expect Republicans to catch up quite a bit once Election Day arrives.

Nevertheless, there’s been a shift in the partisan preferences for the methods of early voting. In years past, the Democratic lean of early voting has been driven by in-person voting. When it came to vote-by-mail, Republicans used the option just as much — or in some places, to a greater extent — as Democratic early voters.

The pandemic — and most likely Trump’s rhetoric bashing vote-by-mail — has flipped that trend on its head. Democrats are using vote-by-mail to a much greater degree than Republicans, while Republicans are increasing their use of early in-person voting and, in some places, using it more than Democrats.

That doesn’t change the key question for Nov. 3 that’s been front-and-center on previous Election Days: Will Republicans be able to overcome the advantages banked by Democrats in the early vote?

“There’s more people voting by mail than in-person, where the Republicans may have a lead. But the lead is just not as large, and there’s just not as many people voting in person,” said Michael McDonald, a University of Florida political science professor who is organizing a website keeping track of the early vote numbers.

The Likelihood Of A Dragged-Out Count Is Decreasing.

Another refrain voters have heard during the pandemic is that the process of tabulating the election results will take longer than what the public is used to, due to the surge in vote-by-mail. That’s still true in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Michigan, because of those states’ rules limiting the absentee ballot processing work that can be done before Election Day. But in several other states, election experts are feeling more optimistic that results can be reported just a few hours after polls closed.

“In many of these states — Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Texas, Arizona, Ohio —we’re going to have a pretty good indication of what the results are sometime in the middle of night or very early morning,” Becker said.

That prediction comes with the caveat that if the margin is super close in any of those states — within a few thousand votes — such an indication will have to wait for the counting of overseas ballots, provisional ballots and whatever remains of mail-in ballots. And if who wins the White House again comes down to the upper Midwest trio that tipped the 2016 election towards Trump, the onslaught of early votes we’re seeing now won’t make those results come much sooner.

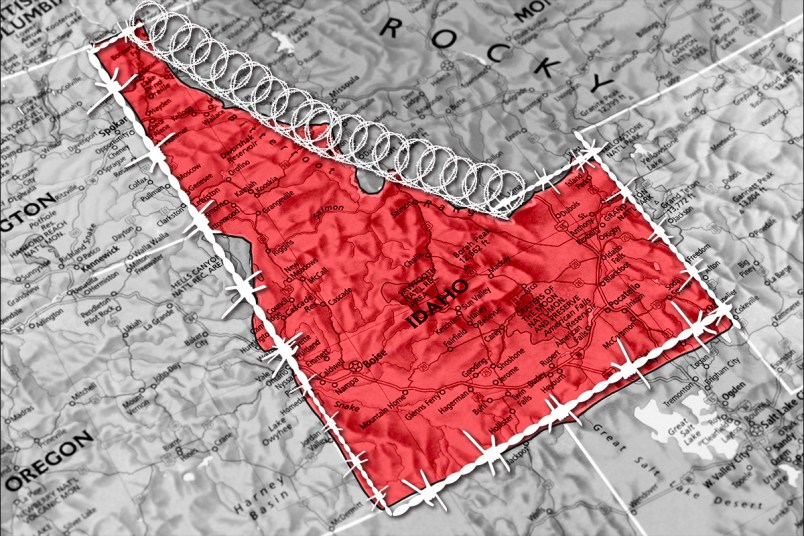

The Lone Star State Is Leading The Early Vote Surge.

Everything is bigger in Texas, including the way its voters are outperforming 2016’s early vote patterns. It ranks number 1 in the country in terms of percentage of total 2016 votes cast that’s already been matched by early voting. The 8.1 million Texans who, as of Wednesday morning, have voted early amounts to nearly 91 percent of the total ballots cast in the state’s 2016’s general election.

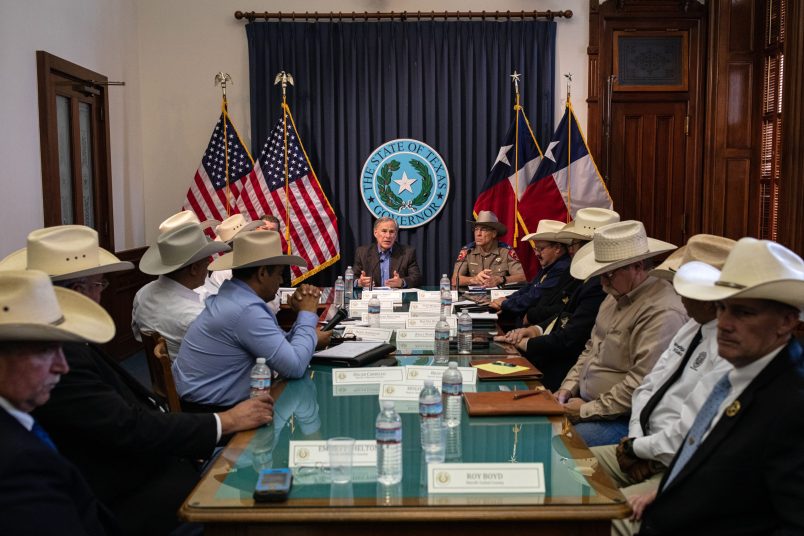

What makes this pattern all the more incredible is that Texas is an outlier in how little it has done to make voting easier in the pandemic. State officials refused to let COVID-19 count as an excuse for absentee voting. While Gov. Greg Abbott (R-TX) did tack on an extra week of in-person early voting because of COVID-19, he limited the options for people who wanted to turn in their absentee ballots in-person.

Some experts credited the steps county officials have taken to make in-person early voting accessible, while others noted that even with the tight absentee rules, way more Texans are using vote-by-mail than usual.

Because Texas’ early data isn’t broken down by party, McDonald said it was helpful to compare it to Louisiana. Louisiana, like Texas, kept absentee voting limited in the pandemic, but has party registration numbers that help track of which party is driving the overall surge.

“Those early-in person voters are unlike in-person voters elsewhere in that they’re probably much more Democratic,” McDonald said.

These Numbers Will Shape How Election Officials Prepare for Election Day Itself.

As mail ballots and in-person early votes are cast before next Tuesday, the universe of possible Nov. 3 voters narrows — making it easier for election officials to plan for an Election Day that was always going to be difficult, given the challenges that the pandemic poses.

In Florida for instance – where mail-voting looks like it will make up an even larger share than what’s usual in the state, which typically sees about a third of its ballots cast by mail — there’s talk of Election Day being “crickets,” Stewart said.

“We have jurisdictions around the country that are saying they have 50, 60 percent of their registered voters having already returned their ballots … and they still have their busiest days ahead,” Tammy Patrick, a vote-by-mail expert at the Democracy Fund, told TPM on Monday. “That has me believing that we will be in a pretty good place at the end of the day on [Nov. 3], but it all remains to be seen.”

The flip side for election officials who are now going to be banking on 20 or 30 percent of their voters showing up on Election Day, instead of 80 to 90 percent, is that if they’ve underestimated the overall projected turnout, there could still be some chaos at the polls.

“Let’s say I’m off by a million in my turnout estimate. Four years ago, if only 10 percent are voting early, well then if I’m off by a million on my Election Day, it’s not a big variance,” Stewart said.

But, he explained, when election officials are expecting a much smaller number of Election Day voters due to increased reliance on vote-by-mail and early voting, being off in their turnout estimates by 1 million is a comparatively large miscalculation. Stewart outlined a hypothetical in which Georgia is expecting roughly 2 million voters on Election Day. Underestimating total turnout by 1 million could mean that there will actually be 3 million Election Day voters, causing chaos at the polls. Overestimating turnout by 1 million will mean only 1 million Election Day voters, and polling places will be extremely quiet.

“It could be the range I have to plan for is a multiple of three,” Stewart said.