Update: Hours after TPM published the story below, the 11th Circuit issued a ruling in this case.

For seven years, one case has languished before the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Not letters from outside advocates, not status requests from attorneys, not a motion for a ruling from one party in the case has gotten the court to budge.

But 11 years since the case was filed in the Middle District of Alabama, seven years since it was appealed to the 11th Circuit, and six and a half years since a three-judge panel heard oral arguments in the case, the court has failed to rule.

Multiple appellate lawyers and former clerks at circuit courts told TPM that they could not recall hearing of a case going so long without a ruling.

Arthur Hellman, an expert on federal judicial ethics and professor emeritus at University of Pittsburgh Law School, called it “extraordinary” in a phone interview with TPM.

“If you look at the ethics rules for federal judges — and you don’t need a rule to say this — disposing of cases promptly is one of the primary obligations of every judge,” Hellman said.

The case that has languished before the 11th Circuit pits a homeless Black man against an Alabama sex offender registry law.

Michael McGuire of Montgomery sued the state of Alabama in 2011, alleging that the law violated his constitutional rights. A district court judge ruled in his favor in February 2015, finding that two provisions of the law — the Alabama Sex Offender Registration and Community Notification Act — were unconstitutional.

Alabama’s then-Attorney General Luther Strange appealed the ruling to the 11th Circuit in March 2015.

The case was heard in February 2016 by a three-judge panel.

Since then, the court asked for a supplemental briefing in 2017 for the parties to address amendments that Alabama’s state legislature made to the underlying law.

“If you look at the ethics rules for federal judges — and you don’t need a rule to say this — disposing of cases promptly is one of the primary obligations of every judge.”

Attorneys in the case have made two attempts to push the court to act. In April 2019, more than three years after oral arguments, attorneys for McGuire asked the court for a “status update or, in the alternative, an order and mandate.” The court replied one week later, noting that “the appeal remains pending before the court.”

More than two years later, in June 2021, Alabama’s attorney general filed a motion to the same end.

“This appeal has been pending without a decision for more than five years after oral argument,” the state observed, before citing its opponent’s request for a status update from two years earlier.

The court “granted” the motion, but still didn’t rule.

It’s a stunningly aberrant delay, reflected in part by the fact that the attorney general felt the need to file the motion.

“That’s dicey, because you can imagine that if you’re appealing before a panel of judges, you run the risk that you’re going to piss them off,” Jonathan Nash, a professor at Emory University Law School who studies the federal judiciary, told TPM. “Now, you’re filing a motion trying to get them to rule, and demanding an answer.”

David Pozen, a law professor at Columbia who clerked on the D.C. Circuit, told TPM that the “federal judiciary has a strong norm of resolving cases reasonably expeditiously.”

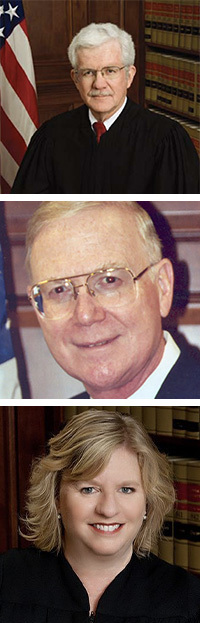

The 11th Circuit panel was comprised of Jill Pryor, an Obama appointee; Kenneth Ripple, a Reagan appointee visiting from the 7th Circuit; and Ed Carnes, who was chief judge of the 11th Circuit at the time that arguments were heard. Carnes took senior status in June 2020, and departed his position as chief judge of the circuit.

There’s some irony in Carnes being involved in such a delayed case. Chief judges typically work as the enforcers on the circuit courts. If judges are late in filing their opinions, it falls to the chief judge to ensure that cases are moving ahead on time.

“The chief judge would bring pressure on any panel that was slow or who was slowing things down,” Pozen said, recalling his experience on the D.C. Circuit. “I’ve never heard of a delay like six-plus years.”

“In any organization, you need to have somebody at whose desk the buck stops, and in the federal courts of appeals, that’s the chief judge of the circuit,” Hellman, the judicial ethics scholar, told TPM. “That includes many formal steps and formal actions, but it also includes the informal, pick up the phone and call the colleague.”

Since Carnes stepped down, Judge William Pryor has taken over as chief judge of the 11th Circuit.

For the plaintiff, Michael McGuire, the case is straightforward.

McGuire was convicted in 1986 of first-degree sexual assault, second-degree assault, and menacing in Colorado state court. The crime involved the use of a kitchen knife and wine bottle as weapons. He served three years in prison and one year on probation.

After prison, McGuire moved to Washington, D.C., where he became a jazz musician and hairdresser and got married, according to a 2015 ruling from an Alabama federal judge in the case. In 2010, McGuire moved with his wife to Montgomery, Alabama, where his brother is an attorney.

Alabama passed its sex offender registry law in 2011. Among other things, the law mandates that anyone convicted of a list of crimes that qualify as “sex offenses” under Alabama’s criminal code — which range from public indecency to sexual torture — anywhere in the United States at any time must comply with a list of requirements that the district court judge in the case described as “the most comprehensive, debilitating sex-offender scheme in the land.”

Offenders must request a travel permit — by providing among other things the dates of travel and places of stay — from local law enforcement before leaving their county, and are restricted in where they can live.

Those affected by the law must register at least four times per year; homeless residents must register once a week with both county and municipal law enforcement.

All this, a federal judge found, left McGuire homeless and living under a bridge.

“Mr. McGuire has shown that he would live with his wife and not under a bridge absent ASORCNA’s residency restrictions,” the judge wrote, ruling that the dual registration and travel requirements were unconstitutional.

Hellman, the judicial ethics scholar, suggested that the delay amounted to dereliction of duty.

“It’s always possible to take a little more time and improve the opinion marginally, but that’s not what appellate judges are supposed to do,” he said. “They’re supposed to resolve disputes.”

Nash, the Emory University legal scholar, said that he was “at a loss to explain it.”

The reason for the 11th Circuit’s failure to rule on McGuire’s appeal has not been explained.

“No matter how complex the issues in a case, the court is obliged to decide it. The court of appeals shouldn’t need seven years, or five years, or two years.”

The court did issue one brief explanation in 2021, responding to the Alabama attorney general’s motion for a ruling.

“This case involves considerable unsettled law and a number of complex issues,” the court wrote in a minute order issued two months after Alabama’s request. “Since it was submitted, the Alabama legislature amended the relevant statute. The judges on the panel have expended a great deal of effort and spent considerable time researching and analyzing all of the issues and writing about them.”

Both Alabama’s attorney general office and attorneys for McGuire declined to comment to TPM for this story. The 11th Circuit Court of Appeals did not return repeated requests for comment.

Hellman added that the Supreme Court and other courts around the country routinely resolve “the most complex and difficult” disputes in less than a year.

“No matter how complex the issues in a case, the court is obliged to decide it,” he said. “The court of appeals shouldn’t need seven years, or five years, or two years.”

The panel added in its August 2021 order that it “has worked diligently on the case and continues to do so, but more work remains to be done.”

“The motion for a ruling at the earliest practicable time is GRANTED,” it wrote, 13 months ago.