An object, cloaked in an aura of glamor and cool, is, or at least feels, ubiquitous in American society. The object is a clear threat to public health — though that fact often gets eclipsed by arguments emphasizing the rights of those who like to use the object. Powerful, monied and well-connected special interest groups stand behind the object, and work fervently to thwart regulation and restrictions on it.

Today, that object is a gun. In our recent past, it was a cigarette.

Cigarette smoke clouding public spaces — airplanes, restaurants, offices — was the norm for decades. For a long time, there was no organized resistance to its pervasiveness.

The federal government was completely unmoved by the pleas of anti-tobacco activists — most of whom, especially in the movement’s nascent years, were women — and took decades to get meaningfully involved. The Food and Drug Administration didn’t even get the authority to regulate tobacco until 2009.

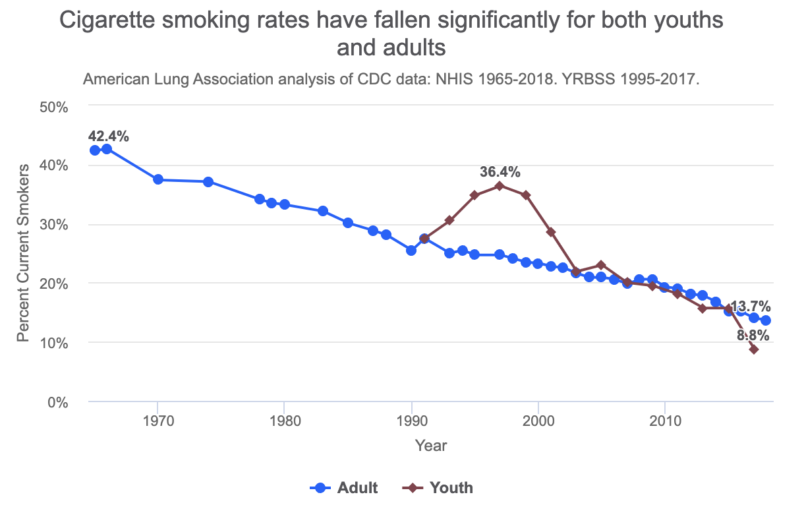

Despite the government’s inertia, the anti-cigarette movement was incredibly successful. In 2020, the most recent year for which the Centers for Disease Control has public data, 12.5 percent of Americans over the age of 18 smoked. That’s a dramatic plunge from the 42.4 percent of adults who smoked in 1965, with the trendline largely sloping down since then.

While cigarettes still kill more than 480,000 Americans a year according to CDC estimates, they have been all but banished from the public square. Grassroots activists, mostly operating at local levels of government, thwarted the tobacco industry despite its deep pockets, congressional lackeys, extensive advertising campaigns, Hollywood buy-in, disinformation infrastructure and white-shoe law firms.

Can their playbook be replicated in the fight against guns?

The People vs. Joe Camel

Smokers, like gun owners, have always been a minority — but a societally powerful one.

“In the 20th century, the smokingest segments of Americans were white men; now, the most gun owningest segments of Americans are white men,” Sarah Milov, associate history professor at the University of Virginia and author of “The Cigarette: A Political History,” told TPM. “The consequence of that for non-gun owning Americans is that they live in a world where public space is governed by the political demands and practices of what is truly a minority.”

The gun and cigarette lobbies spent millions obscuring that fact, presenting guns and cigarettes as foundational and ubiquitous parts of American life. Resistance to them, then, is futile — even unpatriotic.

As early as the 1950s, studies were linking cigarette smoking and lung cancer. In 1964, the surgeon general published a major report underscoring that cigarette smoking causes premature death from lung cancer, bronchitis, heart disease and emphysema.

The report led to a tobacco-friendly Congress passing the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act, which put the surgeon general’s warning on cigarette packs — a regulation the tobacco industry okayed, since it framed smoking as an informed choice by the smoker and not corporate manipulation — and a few years later, to ban broadcast advertising for cigarettes. Tobacco companies largely shifted that money to other forms of advertising, like billboards.

“Congress was where strong tobacco control went to die,” Milov said.

So activists had to find another way. With the doors of the Capitol shut to them, they took up the great American pastime of being a pain in the ass at local government meetings.

“We couldn’t win at the federal or even state level because it was too out of sight and the lobbyists and money and backroom deals were just too strong,” Stanton Glantz, a retired professor of medicine at University of California San Francisco and tobacco control author and activist, told TPM. “So we started doing local activism and passing local ordinances — we didn’t win every campaign, but we won more than we lost.”

“Congress was where strong tobacco control went to die.”

Activists started racking up wins by changing the perception of smoking in public places.

The tobacco industry had had great success in focusing on the rights and autonomy of the smoker. The anti-smoking movement successfully shifted the conversation to the rights of those around them, and the rights of everyone to not be manipulated by the tobacco industry. That argument was bolstered by the growing scientific consensus in the ‘80s that second-hand smoke too was dangerous and damaging to people’s health.

Building into the ‘90s, activists had great success in focusing on workplace smoking bans.

“We were getting defeated because tobacco companies came in and said it was about choice: If a customer doesn’t like smoke in a restaurant, they can go somewhere smoke-free, and we couldn’t really counter that,” Mike Siegel, currently a visiting professor at the Tufts University School of Medicine whose research has centered on alcohol, tobacco and firearms, told TPM. “So we said, let’s make this about the workers and not customers, who don’t have a choice but have to make a living and support their families. That was the beginning of the end.”

They also appealed to companies’ bottom lines: smokers take a lot of breaks, damage equipment and often get seriously sick.

By the mid-’90s, states were filing Medicaid lawsuits against the tobacco companies to recover billions of dollars lost in health care costs of treating smoking-related illnesses. In 1998, 52 state and territory attorneys signed a Master Settlement Agreement with the country’s four biggest tobacco companies. It forced the companies to, among other things, pay the states involved billions annually and greatly restricted what kind of advertising they can do.

By the late ‘90s and early 2000s, many states passed comprehensive bans, and smoking in public was becoming increasingly uncommon.

Over 30 years had elapsed since the surgeon general’s blockbuster 1964 report.

Taking The Cigarette Fight To Guns

David toppled Goliath. It took decades, but grassroots activists succeeded in changing the culture enough that cigarettes were exiled from public spaces and have become a habit for fewer and fewer Americans.

Experts think there are lessons to outsource to the fight for gun regulation: the anti-tobacco movement was coalitional, with outposts in every state; activists quickly realized the power of changing the narrative and stigma around public smoking, and of centering the rights of nonsmokers being harmed by cigarette smoke; instead of despairing at Congress’ coziness with big tobacco, they took the fight to local government.

But the gun industry has also learned from tobacco’s mistakes.

The tobacco companies were caught flat-footed in the face of local activism, busy securing their Washington alliances. The gun lobby is loath to make the same mistake.

Gun companies and their conservative helpmates have successfully gotten preemption statutes passed in the vast majority of states, which prevent or limit local governments from regulating firearms and ammunition. Local governments, then, are subject to state regimes, which, under Republican leadership, are often quite lenient with access to guns.

Some states have taken their preemption statutes to the extreme, actually including fines and liability for local officials who violate them. Arizona allows courts to remove from office and fine local officials who violate the statute; Kentucky makes them criminally liable.

“ALEC was really active in the 1990s in encouraging states to pass tobacco preemption laws because the non-smokers’ rights activists succeeded in enacting tobacco controls at the city level,” Milov said. “The gun industry learned from the tobacco playbook.”

ALEC, the American Legislative Exchange Council, is a coalition of conservative state lawmakers and private sector representatives who draft and distribute legislation for states to copy.

By choking off the power of local governments, the gun industry narrowed the pool of legislators it has to politically pressure. The preemption laws also block the momentum that anti-tobacco activists enjoyed: consistent wins on the local level, where officials are more attentive to their constituents, are much more heartening to a movement than trying and failing to convince Republican state legislators in heavily gerrymandered districts to sever their NRA ties.

The gun industry also benefits from a seriously devoted fan base. Many — though far from all — gun owners see their firearms as more than a recreational tool or even a means of self defense. The cult of the gun has grown so powerful that some owners consider it a part of their identity: shorthand for individualism and freedom, for triggering the libs and intimidating a federal government that supposedly wants to change their way of life.

Even the tobacco industry’s biggest customers largely lacked that fervor.

“Even when the United States and much of the western world was at its smokiest in the ‘50s and ‘60s, the vast, vast, vast majority of smokers had begun smoking as youths and by the time they got older, did not want to be smokers anymore,” Milov said. “It wasn’t a point of pride.”

The gun companies, of course, also benefit greatly from the Second Amendment, which a conservative Supreme Court interpreted as applicable to individual gun ownership and an even more conservative iteration is now poised to expand.

“There is a public perception that these are powerful Goliaths that cannot be beaten, and there is pessimism about ever getting anything done.”

The gun industry, then, which already has a more favorable hand than its cigarette counterpart, has further stacked the deck to dampen activist enthusiasm.

But still, there’s another intangible at play. The damage cigarettes cause to smokers and those around them is gruesome: blackened lungs, hacking coughs, and, often, premature death. But those bodily tolls still take years — the CDC estimates that smoking shaves about 10 years off a smoker’s lifespan.

The damage that guns do to their owners and bystanders, which we see play out on a near daily basis, is even more extreme, though the annual death toll is still much lower than that of cigarette-related deaths. Children, teachers, grocery shoppers, music lovers, moviegoers, completely random passersby are murdered in the span of seconds. Many more, who often don’t rate any coverage at all, sustain permanent and life-altering injuries. Suicides make up the majority of gun deaths in America, and there is a strong link between states with pervasive gun ownership and higher suicide rates.

For a long time, the gun conversation in the United States has centered on gun owners’ rights. Now, as part of a movement growing out of high profile gun massacres, people are increasingly talking about their right not to be shot. You can hear the anti-tobacco activists’ echo.

“There is a public perception that these are powerful Goliaths that cannot be beaten, and there is pessimism about ever getting anything done,” Siegel said. “Today, people are so frustrated that Congress is never gonna do anything — 20 years ago, they were saying the same thing about tobacco.”