Unlike any other nation’s, ours is a history uniquely and inextricably intertwined with guns. Pick any era from our past and you’re likely to find a firearm that speaks to the state of our Republic at the time. But the bargain that America has made with guns has always been a Faustian one. For every gauzy tale of Minutemen bravely firing the first shots of Revolutionary freedom with their Brown Bess muskets at the Battles of Concord and Lexington, there is the less well-told story of slave traders and plantation owners relying on those same weapons to enforce a vast infrastructure of human subjugation. The Winchester repeating rifle, “the gun that won the West,” did so in large part by inflicting massive casualties on Native Americans and helping to forcibly inter them into desolate reservations. The Thompson submachine gun that American G.I.s bravely stormed the beaches of Normandy with to defeat Hitler already had a sordid legacy as the preferred weapon of Prohibition-era gangland violence.

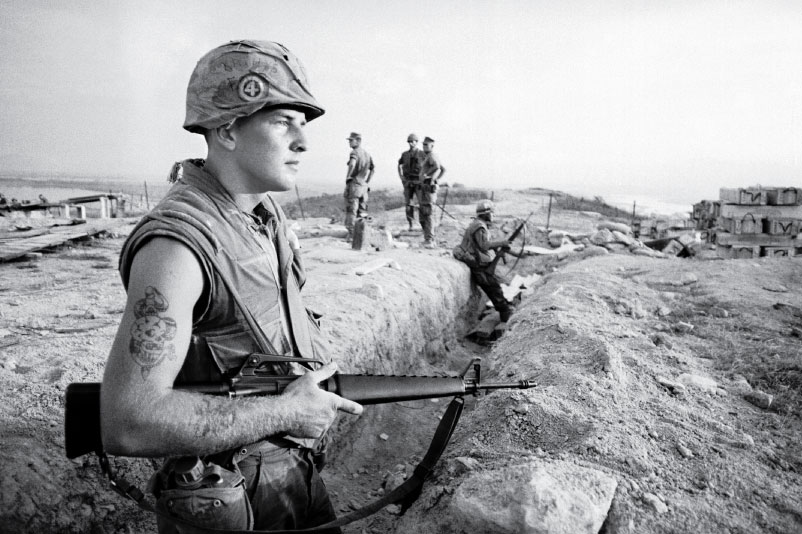

This historical through-line of arms continues to this day. And for the past 50 years, no other single firearm has assumed the mantle of iconic American gun — with all the dire consequences that entails — quite like the AR-15. In its military incarnation — as the M-16 and M-4 automatic rifles — its distinctive silhouette has become an internationally recognized emblem for American power and influence. Here at home, civilian sales of the semi-automatic Colt AR-15 and its many competing knockoffs have skyrocketed in recent years and now total in the millions.

The AR-15’s reach into our nation’s culture is no less remarkable. It’s appeared in hundreds of movies, and even co-starred with Hollywood’s archetype of the American gunfighter, film legend John Wayne. You’ll find its image on T-shirts, flags, and body parts. It’s spawned countless Internet memes. It’s been sold, in toy form, to untold numbers of children. You can buy a working version of the weapon with a pink, Hello Kitty design or in star-spangled, red, white, and blue livery. There are a near infinite number of ways to accessorize and customize it. A Congressman once offered one up as a campaign fundraising prize. (It’s also been banned by Congress—but not really.) It’s increasingly carried as a symbolic totem at protests and counter-protests and its presence among dozens of members of the crowd at last week’s Dallas shooting added to the chaos. And, as perhaps the ultimate signifier of modern-day American status, it now has its own TV show.

The story of the AR-15 is a quintessentially American one. Which is to say it combines the classic elements of war, cheap salesmanship, second chances, bureaucratic incompetence, and a time-honored tradition of trying to squeeze every last dollar out of a deal. From such compromised origins grows a long, checkered history, one where this weapon has often exacted a lethal toll far beyond its makers’ expectations. It’s a deadly dichotomy that began in the jungles of Vietnam and continues to plague Americans here at home to this day.

Born of War, Flawed from the Start

The truth is, no one really liked or wanted the AR-15. Manufactured by ArmaLite, a small, private arms company from California — hence the “AR” designation, for ArmaLite Rifle — the sleek, all-black, .223-caliber automatic rifle’s initial military tests were met with skepticism in the late 1950s. Though the small, light AR-15 had little to no recoil, which made it more accurate when fired on automatic (multiple shots per trigger pull), the weapon had malfunctioned during tests. In the end, the Army preferred the larger 7.62 mm (.30 caliber) rounds of its incumbent infantry weapon, the longer and heavier M-14, which had just been approved in 1957.

But by the early 1960s, fate had shifted in the AR-15’s favor. First, the civil war in Vietnam had intensified, and the South Vietnamese — and the U.S. Special Forces troops (“advisors”) fighting alongside them — were reporting back to battlefield commanders that they were outgunned by the enemy’s fast-firing, Chinese-made AK-47s, which also fired 7.62mm rounds. “Just when the American armed services grasped that they needed a smaller automatic rifle, there was nothing suitable in the government design pipeline,” explains C.J. Chivers in The Gun, his excellent history of the AK-47. “Instead,” Chivers notes, “the Pentagon reached into private industry for the AR-15.” And while numerous mid-level military officials helped grease the wheels of the civilian AR-15’s rapid transition into the military arm dubbed the M-16, two men at the very top of Pentagon, whose legacies were forever be tainted by their leading roles in the Vietnam War, were instrumental in the process.

The first of these was the Kennedy administration’s Defense Secretary, Robert McNamara. Thanks to his technocratic, “Whiz Kid” view of warfighting, he was predisposed to hate the stodgy M-14 and desperately wanted a replacement. Also helping the cause was notorious Air Force General Curtis LeMay, who was on the receiving end of a very savvy, personalized sales pitch by a Colt salesman. Colt had bought the right to manufacture the AR-15 from ArmaLite after the Army’s initial rejection left that company struggling. But lacking a civilian customer base, Colt too was at risk of losing its investment if it couldn’t get the military to purchase it.

As Chivers recounted in his book, then Air Force Vice Chief of Staff LeMay attended the birthday party of a defense contractor in 1960. During the festivities, an AR-15 was conveniently produced, and LeMay was offered the chance to squeeze off a few rounds at some target watermelons with the new rifle. Naturally, they disintegrated when hit. The experience apparently left a lasting impression. By 1962, LeMay had ordered 8,500 of the weapons for the Air Force. This followed an earlier, smaller order of AR-15s by McNamara in late 1961 to outfit U.S. Special Forces and South Vietnamese Army regulars as part of a battlefield test.

The results of that confidential test, published by the Defense Department in August 1962, portray a weapon of uncanny effectiveness, accuracy, and lethality. Still, owing to previous reports of mechanical problems during initial testing, the DoD authors took care to note the “controversy surrounding the weapon,” and thus the “particular care” that was taken to ensure the tests had been “objective.” This sober, pseudo-scientific tone was little more than a put on, however. The gathering momentum in the Pentagon for the AR-15 had ensured the report would be little more than a self-fulfilling prophecy. Nevertheless, the tactical anecdotes of the AR-15’s firepower are still gruesome. One report, of a South Vietnamese Ranger platoon’s ambush of Viet Cong guerillas on June 9, 1962, stands out. It documents in grisly detail the carnage of the (all fatal) wounds inflicted, including an abdominal cavity exploding and a leg splitting apart along its entire length.

Though both Colt and the military colluded to hype the M-16’s every feature, there’s no denying that the combination of the weapon’s ultra-high muzzle velocity (speed of the round as it leaves the barrel of the gun), and blazing fast cyclic rate made it a splendid killing machine. What’s more, its simple design and low recoil made it fairly simple to learn and operate — traits that would fuel its civilian counterpart’s popularity decades later. And even when fired on semi-automatic (one shot for every trigger pull), the gun was still extremely lethal. In fact, it was over-engineered to a ridiculous degree — one military specification required that rounds fired from the gun had to penetrate a steel helmet at a distance of 500 yards. Much of the fighting in Vietnam took place at distances that were a fraction of that.

“Chivers tells of one marine gunnery sergeant that started carrying an AK-47. When confronted by a lieutenant colonel about why he was carrying the weapon of the enemy, the marine replied: ‘Because it works.’”

Still, even the most powerful rifle is no good if it won’t or can’t fire. And from the beginning, performance and reliability issues plagued the Army’s new wonder rifle. Routine jamming was well-documented from the very first tests of the AR-15. But military officials, in concert with Colt, effectively covered it up. Once the weapon was fielded en masse in the extreme conditions of Vietnam, however, the problems multiplied. Rapid inner barrel decomposition, cartridge brass getting stuck in the chamber or even being sheared off (a function of the weapon firing too fast), upper and lower receivers rusting through: all of these became so common that some U.S. soldiers and marines sought out old M-14s on the black market out of desperation. In a surreal scene straight out of a movie, Chivers tells of one marine gunnery sergeant that started carrying an AK-47. When confronted by a lieutenant colonel about why he was carrying the weapon of the enemy, the marine replied: “Because it works.”

The M-16’s reputation finally reached its nadir in May 1967 at the battle of Hills 861 and 881 just north of Khe Sanh, South Vietnam, where widespread breakdowns contributed to the most casualties in a single battle to date. The M-16’s failure rate leaked back to the U.S. via letters home to parents and local newspapers. One Hill Fight survivor’s account made the front page of the Asbury Park Evening Press. In it, he bluntly stated: “Believe it or not, you know what killed most of us? Our own rifle. …Practically everyone of our dead was found with his rifle tore down next to him where he had been trying to fix it.” Finally, the M-16’s deadly impact — upon those who carried it — drew the scrutiny of Congress.

The Ichord report, so called for Democratic Congressman Richard Ichord who chaired the special subcommittee investigating the M-16’s failures, was released in the fall of 1967. Throughout the investigation, the military had stonewalled Congress and, in a particularly callous move, tried to shift the blame onto the soldiers and marines who carried the weapon (and suffered the most from its failures). But while the report concluded that inadequate cleaning and maintenance by individual servicemen did contribute somewhat to the “serious and excessive” malfunctions, it put most of the blame on a lack of quality control and numerous cost-cutting measures by Colt and the “biases and prejudices” of senior military officials involved in the acquisition process, who had allowed Colt to enjoy “an excessive profit on M-16 production contracts to date.”

Despite the public outcry and the report’s shocking findings, Colt’s contract to produce the M-16 was never in jeopardy — Colt still produces the weapon for the U.S. military to this day — and no senior military official was ever held publicly accountable for misconduct. In fact, by the time the Ichord report came out, Colt had quietly already agreed to most of the fixes specified, which made sweeping the whole sorry spectacle under the rug that much easier. Yet while the new, improved design significantly decreased the M-16’s jamming and corrosion problems in Vietnam, Colt never eliminated them before the war’s end.

Crossing Over—Marketing and Mass Shootings

The gun industry and its compliant press had a hand in hiding the M-16’s performance issues. An early civilian test of the weapon by the Shooting Times in October 1966 had uncovered many of the same jamming issues experienced by soldiers and marines in Vietnam, but mostly ignored them. In the test, the rifle malfunctioned 11 times in the first 450 rounds, yet the writer dismissed the problems as random rather than systemic, even though Colt had handpicked the test weapon. American Rifleman, the NRA’s house organ, likewise ran a rah-rah review of the M-16 in May 1967, at precisely the same time the M-16 was betraying U.S. marines so catastrophically. In an unintentionally frank way, the magazine said the gun was “proving itself in Vietnam.”

In his book Making a Killing, gun researcher Tom Diaz has noted that the gun press has typically behaved differently from other enthusiast media. Instead of playing a watchdog role for consumers, over time it has allowed itself to be subsumed into playing the role of industry cheerleader and defender. He notes that gun enthusiast publications routinely participate in gun marketing strategy and planning events, and gun press executives often sit on the boards of gun trade organizations.

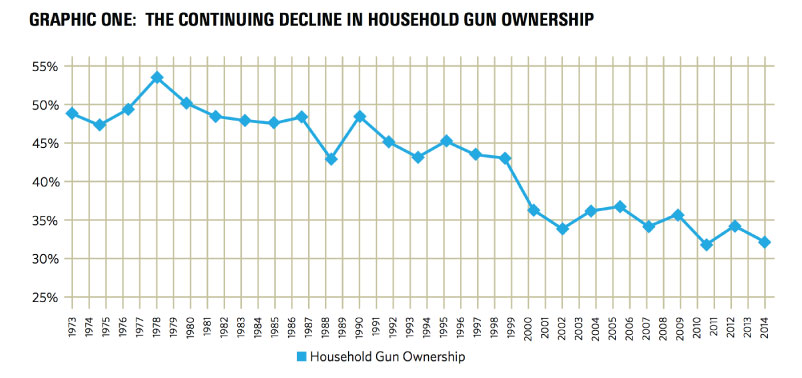

This boosterism became especially critical to the fate of the AR-15 in the post-Vietnam era. The boom in the sale of handguns during the 1960s and 1970s, which generated big profits, had led to a glut. As Bill Ruger, founder of the eponymous gun company, candidly put it to Diaz in 1980: “You have to have new stuff.”

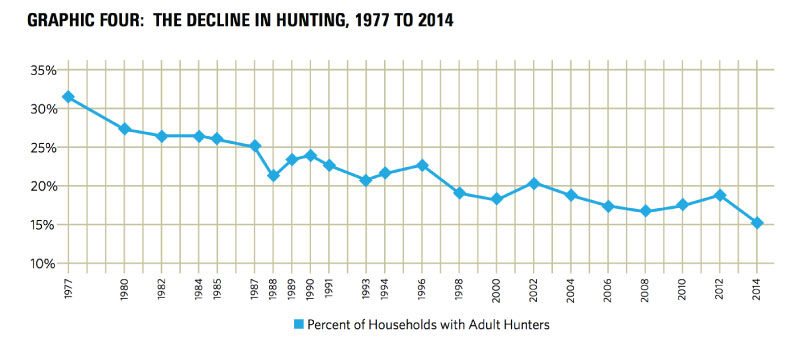

That “new stuff” to market to gun enthusiasts would eventually become assault weapons like the M-16, aka AR-15, which were easily converted to legal, civilian use simply by removing their automatic firing capability. (Since 1986, the sale of new machine guns—that can fire on automatic—has been illegal.) Even so, the initial response to this new weapon among actual gun enthusiasts was cool. This was partly because the AR-15’s small caliber round, though adept at wounding and killing enemy fighters on the battlefield at long ranges, lacked the necessary energy to consistently bring down traditional big game like deer beyond distances of 150 yards. (Several states ban AR-15s and all other .223-caliber rifles from deer hunting for this reason.)

This limits the AR-15’s real ‘sporting’ uses to target shooting and varmint hunting, but many owners talk of being attracted to the gun simply due to the adrenaline rush of firing it. A recent National Shooting Sports Federation (NSSF) survey of more than 7,000 assault weapons owners found that recreational target shooting was the number one reason (8.9/10) given for owning an assault weapon, while small-game hunting ranked fourth (6.2/10). Collecting (6.3/10) was third most popular, while big game hunting ranked next to last (4.4/10). Number two on the list, though, was home defense (7.7/10). This “defend the castle” notion has been a key component in the AR-15’s ascent, says Diaz. In particular, he points to the rise of the right-wing survivalist movement in the 1980s as helping to lay the first foundation for the demand for assault weapons. In Richard G. Mitchell Jr.’s 2002 book on the survivalist movement, Dancing at Armageddon, he noted that by far, the most popular step in crisis preparation was to acquire firearms.

It wasn’t until 1989 that these trends reached a tipping point, however. The trigger for the assault weapon boom — in what has become a macabre, but now all too familiar phenomenon — was a mass shooting using an assault weapon. The Cleveland Elementary shooting in Stockton, California was that era’s Newtown massacre. A lone gunman carrying a 9mm pistol and an AK-47 killed five children and wounded 30 others before committing suicide. Even though assault rifles and assault pistols were involved in a tiny fraction of total gun crimes at the time — some studies put the figure as low as 2% — public outcry for a ban grew quickly in the aftermath of Stockton. And so too did demand for the AR-15, as a ‘beat the ban’ buying frenzy took hold. By 1991, Colt and Bushmaster, one of the first companies to begin producing a knock-off of the original Colt AR-15, had tripled their production of ARs from just five years earlier. Those numbers would double again by the passage of the 1994 Crime Bill, which banned new sales of certain semi-automatic, military-style rifles and pistols capable of accepting large-capacity magazines.

The Ban that Backfired

Polls from the 1990s showed strong majorities of the public in favor of the assault weapons ban, with anywhere from two-thirds to four out of five Americans backing the law. Even the NRA had given its grudging support to the ban — an almost unthinkable occurrence now.

Despite all this good will, a 2004 Justice Department study found the ban, which was riddled with easily flouted loopholes, to be a failure on almost all fronts. Gun manufacturers soon adapted to the new regulations and exploited the ban’s clumsy definitions. For example, simply removing a flash suppressor or a lug for affixing a bayonet from some banned AR-15s was sufficient to make them legal again. After a brief lull, partly due to oversaturating the market in the years leading up to the ban, AR-15 sales surged again to record highs in the late 1990s. And some manufacturers, like Bushmaster, all but taunted Congress by advertising new, “Beat the Ban” versions of the AR-15 that featured minor, cosmetic changes to the original.

“The ban really was a lost opportunity,” says Diaz, who served as a lead staffer on the House Crime subcommittee that helped write the bill. “It squandered a lot of momentum for curbing these types of guns and, after it passed, it served as a turning point, where any space that had existed between the NRA and the gun industry disappeared.” The industry had prospered while openly undermining the ban, while the NRA had ostensibly supported it; it was a public disconnect that the lobby wouldn’t let happen again.

Moreover, the episode served as a powerful lesson about the marketplace. If a few gun manufacturers could rack up big sales of AR-15s while the rifle was ostensibly prohibited, imagine the profits to be had without a ban. The industry didn’t have to imagine for long. In 2004, with a pro-gun president in the White House and Republicans in control of both houses of Congress, the ban’s built-in 10-year sunset provision kicked in with no real effort to extend it. Less than a year later, the gun industry achieved another one of its most sought after goals when the GOP-controlled Congress passed a bill that shielded gun manufacturers and dealers from liability lawsuits.

Let a Thousand AR-15s Bloom

With the ban expired and gun liability lawsuits neutralized, lethal weapons like the AR-15 became even less of a business risk and more of a sure thing. As a result, any qualms about hopping aboard the assault weapons bandwagon soon disappeared in the gun industry. Smith & Wesson, which had focused almost exclusively on producing pistols and revolvers since its founding in 1852, unveiled in 2006 its own M&P 15, which was the same model used in the 2012 movie theater mass shooting in Aurora, Colorado.

Assault weapons sales rose during the Bush years, but they soared during Barack Obama’s candidacy and presidency when the gun industry warned repeatedly that Obama wanted to do away with the Second Amendment. The NRA and other gun organizations seized on Obama’s April 2008 comments about disaffected white working class voters “cling[ing] to guns and religion” as a rallying cry. After he was elected in November, guns sales rose past one million for the month, and even though he all but ignored gun policy during his first term, the numbers continued to be high. And this trend included assault weapons. A 2010 NSSF survey found that four out of five owners of AR and AK-type assault rifles had bought or received their guns in the previous three years.

“Assault weapons sales rose during the Bush years, but they soared during Barack Obama’s candidacy and presidency when the gun industry warned repeatedly that Obama wanted to do away with the Second Amendment.”

Fueled by this “Obama effect” — his reelection in 2012 coincided with the best month for gun sales in decades — every mainline gun manufacturer now sells an AR-15 model. Even Bill Ruger’s company ultimately gave in. In a 1994 interview with the New York Times, Ruger had made a point of differentiating his sector of the gun industry from the one generating all the bad front-page news: “Most of us don’t even make the guns that are glorified the most—the assault-type weapons and the like.” By 2014, though, his company was rolling out its own AR-15.

Gun industry experts report the AR-15 business continues to be brisk; it spiked yet again after the San Bernardino terrorist attack last December. But because the ATF doesn’t track sales down to the specific model level, it’s difficult to get an exact figure of how many AR-15 variants are selling each year and how many in total there are in the country. After the 2012 Newtown massacre, Slate combined a number of different data points and sales numbers to come up with a very rough guess of 3.75 million AR-15-type rifles.

Though assault weapons still remain a tiny fraction of the total U.S. gun population, they’re notably over-represented in mass shootings. In Gary Kleck’s book Targeting Guns, he found that assault weapons or other semiautomatic weapons with large-capacity magazines were used in 6 out of 15 mass shootings between 1984 and 1993. The Mother Jones database finds some kind of assault rifle has been used in nearly a quarter of mass shootings since 1982. In several of the most deadly, high-profile examples — Aurora, Newtown, Roseburg, and San Bernardino — the shooters used legally obtained, post-ban AR-15s to do their killing. (The shooter in last month’s Pulse Orlando massacre also used an assault rifle, but it was a Sig Sauer MCX, not an AR-15, despite initial reports to the contrary.)

“The gun industry is promoting the AR-15 as this new American icon, ‘America’s Rifle,’ and the military aspects of these guns play an increasingly important role in that effort,” explains Josh Sugarmann, executive director of the Violence Policy Center, a non-profit gun control research and advocacy group in Washington, D.C. The civilian gun market has now become larger and more lucrative than the military/law enforcement markets. This is due, in part, to the vast number of AR-15 add-ons for sale — from laser sights to night vision scopes to flash suppressors — which have become a major profit center for gun companies. While the average AR-15 costs roughly $1,000, add-ons can each cost up to hundreds of dollars more and a large majority of assault weapons owners have at least one accessory on their weapon. The myriad after-market gadgets available for the AR-15 has prompted some to call it “Legos for grownups” and Wired dubbed the rifle the world’s first “maker” gun. But the high-tech nature of these gadgets further blurs the line between military and civilian capabilities, as many of the same sights, scopes, and other accessories that Special Operations units now outfit their automatic M-4 rifles with are also commercially available to the public.

This strategic devotion to guns like the AR-15 within the gun industry as a whole played out at one of the industry’s biggest trade shows three years ago. Shortly after the Newtown massacre, the Eastern Sports and Outdoors Show announced that it would temporarily ban AR-15s from its 2013 exhibition as a gesture of respect and solidarity with the victims. The angry boycott from gun distributors and manufacturers that followed quickly scuttled the event. A year later, the NRA had taken over the show, renamed it, and made its priorities clear: “This year’s show will expand the presence of firearms, including modern sporting rifles.” What is a “modern sporting rifle,” otherwise known as an “MSR?” An assault weapon like the AR-15.

Have the Guns the Bad Guys Have

The new “MSR” tagline is all about re-branding guns like the AR-15 with a much cooler (less killer) 21st century vibe. To push this message, magazines like the NRA’s American Rifleman now invariably attach scare quotes around phrases like assault weapon or assault rifle to delegitimize them as left-wing political propaganda terms. Never mind that, for decades, these same gun enthusiast magazines and organizations had used these very same phrases.

Hand in hand with this language policing is a disingenuous effort to define down the lethal capabilities of guns like the AR-15. Because a legally sold AR-15 can only fire on semi automatic, gun rights advocates now routinely claim that it can’t be considered a true assault weapon like the military’s M-16 or M-4, which can fire on automatic. This is a classic distinction without a difference. Even on semi-automatic, an AR-15 can empty a 30-round magazine in a matter of seconds. And one study, cited in Diaz’s book Making a Killing, found that shooters who fired the same weapon on semi automatic were more accurate than when they fired on automatic. Also, U.S. Army and Marine Corps training doctrine strongly emphasizes semi-automatic mode for better fire control discipline during combat. In other words, even a civilian, semi-automatic-only AR-15 would be well suited for a military assault.

“A 2013 FBI study of “active shooter” massacres found that out of 160 incidents, only five ended due to armed civilians intervening, while unarmed civilians stopped 21 attacks.”

Chris W. Cox, executive director of the N.R.A.’s Institute for Legislative Action, played down the capability of assault weapons in a 2009 article in American Rifleman. “As you should know, but your non-gun-owning friends probably don’t,” he wrote, “the guns our opponents call ‘assault weapons’ are not ‘high-powered’ when compared to other firearms.” Yes — true enough compared to a .50-caliber sniper rifle or a shoulder-fired missile, but no other civilian weapon platform combines the rapid volume of fire, ease of handling, and high terminal velocity at the target like a military-based semi-automatic rifle mated with a large-capacity magazine. “They really act like bullet hoses because they were, from the beginning, designed to kill,” Diaz says.

Dr. David Newman, the director of clinical research for emergency medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital, in New York City, has seen their effects first-hand. In an interview with The Trace that evoked the early AR-15 field test reports from Vietnam, Dr. Newman talked about the unique and vicious damage these weapons do to the human body:

“The worst is a wound from an AR-15 or AK-47 — high-muzzle velocity weapons, which impart a tremendous amount of kinetic energy into the body. Those are much more destructive. You’re looking at a wound that, externally, is two, three, four times bigger than any handgun wound. …

“And that is reflective of the damage that happens on the inside. When a bullet from a high-muzzle velocity weapon hits the intestines, it’s like an explosion, whereas a low-muzzle velocity can be very similar to a knife going through the intestines; there’s bleeding, but it doesn’t destroy the whole area. A high-muzzle bullet, however, destroys whole areas of body.”

In a 2013 NSSF survey of assault rifle owners, Jim Curcuruto, NSSF’s director of industry research and analysis, stressed the MSR’s expanding base of customers. Still, the survey’s numbers showed that owners of so-called modern sporting rifles fit a fairly narrow profile. They were overwhelmingly male (99%) and married (73%), and nearly six in 10 were 45 years old or older. And though the NSSF survey didn’t report any results on ethnicity, in the past, gun industry experts have bluntly acknowledged the predominately white makeup of its consumers. A 1997 article in Shooting Sports Retailer about marketing to Hispanics was not so subtly entitled: “Gun Industry Must Become Less Racist to Survive in the 21st Century.”

That the AR-15 would become a highly charged symbol of our nation’s polarized political culture was perhaps inevitable. And the intertwining of the weapon into our broader political debate shows no sign of slowing down. Just last month, the NRA’s YouTube channel featured a video of a former Navy SEAL denouncing Hillary Clinton for her “utter contempt for ordinary Americans trying to survive in an age of terrorism” and touting the AR-15 as a “common sense choice” for home defense. In a neat bit of circular, self-reinforcing logic, the choice is justified by saying Americans need to “have the gun the bad guys have.” But the “good guy with a gun” trope being pushed here, an increasingly popular remedy prescribed by gun rights supporters, has been mostly proven to be fantasy. A 2013 FBI study of “active shooter” massacres found that out of 160 incidents, only five ended due to armed civilians intervening, while unarmed civilians stopped 21 attacks. And of course, it is thanks in large part to the efforts of the NRA and the gun industry as a whole that the “bad guys” can easily obtain high-powered, devastatingly lethal assault weapons like the AR-15.

This idea about “good guys” and “bad guys” plays an important role in understanding where the AR-15 fits into our broader culture at this moment. For most adult Americans, the “good guys” and “bad guys” in both real life and the movies used to be easy to identify. As Chivers put it in his book: “The Kalashnikov marks the guerilla, the terrorist, the child soldier, the dictator, and the thug.” The good guys carried an AR. The bad guys an AK. But this is no longer true. Even Navy SEALs promoted by the NRA acknowledge that the guns people carry tell us little about their motives or values. Guns are deadly tools, no more about freedom and liberty than about repression and tyranny. As our own history has shown us time and again, the most popular guns embody both the former and the latter. So too has the AR-15 become the symbolic weapon of choice for both right and wrong, good and bad in our country. In this, it joins a storied tradition, making it fit and proper to call it “America’s Rifle.”