This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis.

With attention focused on the battle for control of Congress, some of the signs went under the radar. But last week’s results offered evidence for an encouraging takeaway: that voters understand the threat posed by our party-driven system of election management in today’s hyper-partisan era — and are eager for solutions.

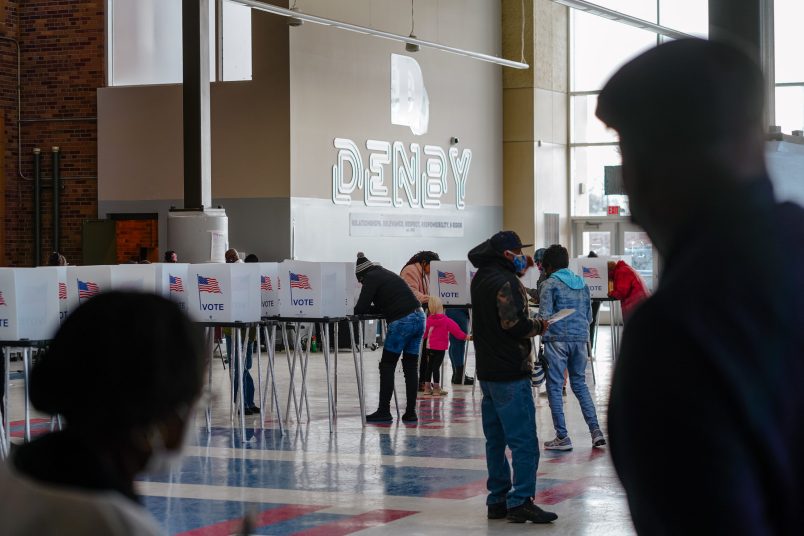

Most important, of course, we now know that all three of the swing-state candidates for secretary of state who have denied the results of the 2020 election were defeated. Over the weekend, the races involving Mark Finchem in Arizona and Jim Marchant in Nevada were called for their opponents, and Michigan’s Kristina Karamo lost by a wide margin on election night — outcomes underlining that, for those running for election official posts, denialism and extremism are electoral losers. Meanwhile, in Pennsylvania, where the secretary of state is appointed by the governor, election denier Doug Mastriano’s comfortable loss in the governor’s race also suggests that, at the very least, he wasn’t helped by his pledge to appoint a like-minded chief election official.

Still, as dangerous as it is, denialism is just a symptom of a larger, systemic issue. Especially given today’s lack of trust between the parties, using partisan politicians to run our elections damages voter confidence, even when election officials do the job impartially. Two less publicized results from Tuesday suggest voters agree.

In Washington, independent Julie Anderson lost her race for secretary of state to the incumbent, Democrat Steve Hobbs, by a relatively narrow margin — currently less than four points. Anderson came close to Hobbs even without the advantages conferred by the backing of a major party, and while being outspent by three to one in a solid blue state that comfortably re-elected its Democratic senator. That isn’t just a testament to her skills as a candidate, and the reputation for expertise and integrity that she earned as a longtime county election director. Central to Anderson’s campaign were her pledge not to accept help from a political party, and her support for making future elections for secretary of state nonpartisan. Her strong showing, then, appears to reflect a desire among voters for election officials who are beholden only to the public interest, and not to partisan interests.

Meanwhile, Michigan voters didn’t just reject an election denier candidate for secretary of state. They also overwhelmingly approved a ballot measure, known as Question 2, that among other reforms aimed to shore up the state’s elections against damaging partisan influence.

In 2020, Republican members of the canvassing board for both the state and the largest county refused to certify results, briefly throwing the contest into turmoil and damaging trust in the outcome. Since then, election deniers have gained spots on county canvassing boards, and efforts to turn certification into a partisan weapon have spread to other states. Question 2, in addition to making changes to some of the rules governing voting access, aims to prevent a repeat of Michigan’s 2020 experience: It confirms that state and county canvassing boards are legally required to certify results as provided by election officials. It also bars the state legislature from playing any role in certification — cutting off another potential route for manipulation that partisans explored last time.

The measure’s passage, then, makes clear that many voters understand how excessive partisan influence in certification was damaging the state’s elections, and were determined to fix the problem. It offers an encouraging sign that, despite the many serious challenges our politics face, voters can still come together on behalf of common-sense reforms.

Tuesday’s results aren’t the only recent evidence that voters grasp the threat and want reforms. A nationwide survey commissioned by our organization and released last month found that voters across the ideological spectrum strongly value impartial election administration. It also found high levels of support for stronger rules aimed at ensuring election officials remain free from close party ties.

There’s a range of steps we can take to reduce the role of partisanship in election administration, and to bolster trust in the process.

Model ethics legislation developed by our organization would bar chief election officials from taking explicit partisan steps that undermine voter trust — like endorsing or raising money for other candidates. The bill would make it illegal for election officials to use their “official authority to influence or interfere, or attempt to interfere, with the outcome of any election” — ensuring that election officials represent the interests of voters, not parties.

A separate model bill would set qualifications for candidates for chief election officer, including experience running elections — a requirement that would have stopped nearly all the election- denier secretary of state candidates this year from running. Both measures would shift the demographics of the candidate pool for these posts away from partisan politicians and toward election professionals. These bills are already gaining sponsors from both parties for introduction in state legislatures next year.

States should also change how they choose their chief election official. One option is nonpartisan elections, which can be combined with the kind of ethics requirements outlined above to ensure that candidates are truly nonpartisan in more than name. An even more effective solution is for states to select chief election officials using commissions of experts, along the lines of the merit selection panels that many states use to pick judges.

Make no mistake: Tuesday’s results also showed that America remains as bitterly divided as ever. And the manner in which the election has played out offers no reason to think that the intense partisan animosity that’s taken hold of our politics in recent years is loosening its grip. But that’s exactly why it’s more urgent than ever that we shore up our elections against attempted partisan manipulation in any form. Thankfully, voters appear to be recognizing the need for change.