This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It was originally published at The Conversation.

Promotions for “The End of Men,” Fox News host Tucker Carlson’s forthcoming documentary, lament “The total collapse of testosterone levels in American men.”

Carlson’s central premise is that modern society has devitalized American men. Strength, drive and aggression are no longer in vogue, and Americans, as a result, are become weaker. This, the film implies, has ramifications for the country itself.

The purported remedies – which include tanning one’s testicles – have been easy fodder for critics. But as a historian of physical culture, I see Carlson’s claims as part of a rich heritage of skeptics shouting from the rooftops that American men are becoming devitalized, lazy and effeminate.

Over the past century, these hustlers and politicians have claimed that society is making men weaker. They’ve explained that physical weakness is indicative of moral rot and weakness of character. They have cited recent social problems as evidence. And their rallying cries often have stoked anxieties about some stronger, foreign enemy.

Building ‘he-men’ after the Great Depression

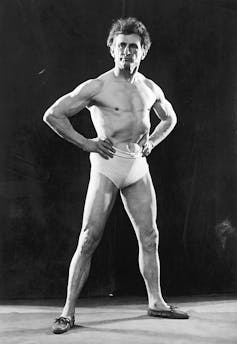

In the 1930s, fitness guru Charles Atlas – whose real name was Angelo Siciliano – embarked on one of the most successful fitness campaigns of all time.

He released a cartoon advertisement titled “The Insult that Made a Man Out of Mac” that told the story of a “97-pound weakling” who is embarrassed at the beach by muscular bullies. Shamed, the boy goes home, builds muscle using Atlas’ workout course, and returns to defeat the bully.

The text accompanying these ads was equally inspirational. Atlas promised to build “he-men,” to make “weaklings into men” and to turn Americans from “Chump to Champ.” The ads appeared in comic books, pop culture magazines and fitness journals. For millions of young Americans, “Mac” was a part of their comic book reading experience.

Older Americans were also susceptible to this messaging.

When interviewed by the New York Post in 1942, Atlas’ business partner, Charles Roman, noted that the Great Depression had been a boon for business, since working-age men tended to link unemployment to a lack of physical prowess.

In this regard, Atlas and Roman were not alone.

One of Atlas’ many fitness rivals during this time, a weightlifting coach and fitness writer named Mark Berry, professed that the Great Depression was spurred, in part, by the weakness of American men.

His solution? A diet and exercise regimen that centered on drinking at least a gallon of milk a day and squatting with a heavy weight draped across the back at least 20 times. Physical bulk and strength were, in Berry’s writings, among the primary ways men could protect their livelihoods and their country.

The rhetoric of Atlas, Roman and Berry, it should be noted, was relatively mild for this line of promotion.

During that same period, fitness writer Bernarr Macfadden had trained navy cadets in fascist leader Benito Mussolini’s Italy and orphans in Portugal, which was then ruled by dictator António de Oliveira Salazar. Upon returning to the U.S., Macfadden contrasted the strength he claimed to see in fascist countries with what he saw as an atrophying American society.

Americans’ unwholesome diets and sedentary behaviors in the 1930s had, in Macfadden’s view, produced a pathetically weak male populace. The solution was strong government intervention in fitness, vegetarian diets and a strict regime of physical fitness in schools.

Much like one of Carlson’s interview subjects who promotes testicle tanning, Macfadden, in his widely read Physical Culture magazine, also pitched a bevy of alternative approaches to revitalize American men, ranging from fasting to all-milk diets.

Fears of a stronger enemy

The notion that American men were weak would eventually migrate to American politics.

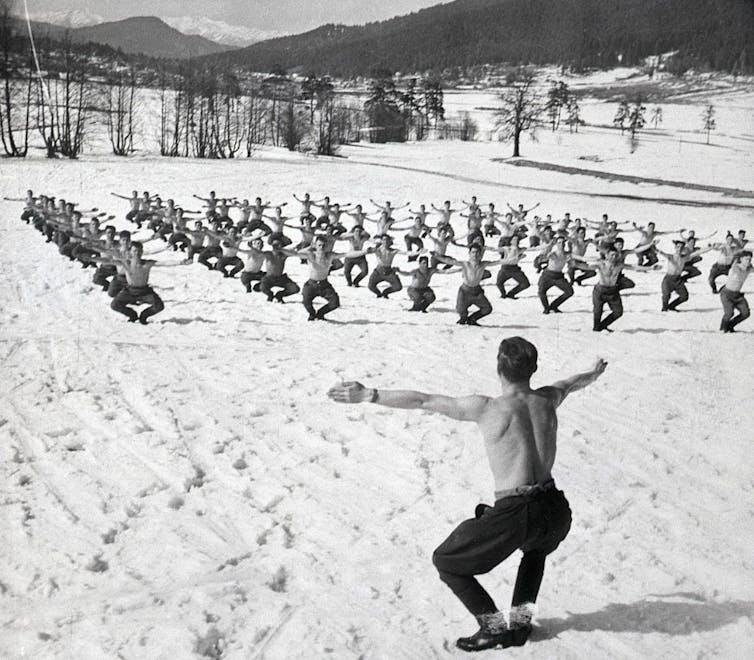

During the 1930s, Germany’s Nazi Party began to invest heavily in gymnastics and sports. Soon, images and videos of tanned athletic German citizens were broadcast around Europe and the United States.

Thus began a period of soul-searching in democratic countries. Was fascism producing physically stronger men and women? What would happen in the event of war?

In the U.K., politicians created state-run programs that mimicked the fascist zeal for fitness.

While calls for America to imitate the fitness regimen of the Nazis – and, to a lesser extent, the Italian fascists – existed, it wasn’t until the Cold War that politicians began to seriously implement policies aimed at truly addressing the nation’s fitness.

In 1956, President Dwight Eisenhower created the President’s Council on Youth Fitness. His reasons for doing so stemmed from medical reports that American children were physically weaker than their European counterparts and fears that the Soviet Union was physically fitter than America.

Eisenhower’s successor, President John F. Kennedy, intensified fears about the nation’s declining vigor. Writing for Sports Illustrated in December 1960, then-President-elect Kennedy published an article titled “The Soft American” to encourage American citizens – in particular, men – to take their fitness seriously.

Sociologist Jeffrey Montez De Oca coined the term “muscle gap” to describe this anxiety. Taking its name from the “missile gap” – the perceived superiority of the USSR’s quantity and quality of missiles over America’s – it refers to the perceived weakness, and softness, of American men’s bodies compared to those of their communist counterparts. A soft body was indicative of a soft mind – and, worse yet, could even make one vulnerable to communist ideology.

A different flavor of the same thing

The Cold War may have ended, but fears that American men’s weaknesses pose a threat to the country have never gone away.

In 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a notice claiming that obesity was threatening national security. In November 2021, Republican Sen. Josh Hawley delivered a speech in which he argued that changing gender norms were destabilizing men’s sense of purpose – and were part of a broader project by “the Left” to “deconstruct” men.

The social reasons cited in Carlson’s documentary for the decline of men – poor food choices, overweight bodies, a disconnect from nature – form the latest evolution of masculinity crises. If anything, the new version has simply added a sprinkle of vaccine skepticism, fears of declining birthrates and anti-intellectualism.

That the documentary includes footage of JFK voicing his concerns about American children in the 1960s is proof of a much longer lineage. I wonder: Why does this story remain so powerful in the American psyche? Why is a subset of Americans so eager to believe that they, or their counterparts, are weak?

Given what we know of this history, perhaps the most pertinent question to ask is what golden standard the men of today are being compared with.

Conor Heffernan is an assistant professor of Physical Culture and Sport Studies at University of Texas at Austin.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.