This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis.

The world watched in July 2021 as extreme rainfall became floods that washed away centuries-old homes in Europe, triggered landslides in Asia and inundated subways in China. More than 900 people died in the destruction. In North America, the West was battling fires amid an intense drought that is affecting water and power supplies.

Water-related hazards can be exceptionally destructive, and the impact of climate change on extreme water-related events like these is increasingly evident.

In a new international climate assessment published Aug. 9, 2021, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warns that the water cycle has been intensifying and will continue to intensify as the planet warms.

The report, which I worked on as a lead author, documents an increase in both wet extremes, including more intense rainfall over most regions, and dry extremes, including drying in the Mediterranean, southwestern Australia, southwestern South America, South Africa and western North America. It also shows that both wet and dry extremes will continue to increase with future warming.

Why is the water cycle intensifying?

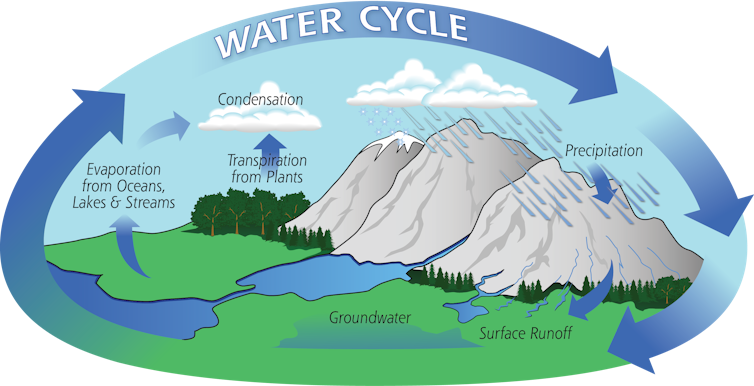

Water cycles through the environment, moving between the atmosphere, ocean, land and reservoirs of frozen water. It might fall as rain or snow, seep into the ground, run into a waterway, join the ocean, freeze or evaporate back into the atmosphere. Plants also take up water from the ground and release it through transpiration from their leaves. In recent decades, there has been an overall increase in the rates of precipitation and evaporation.

NASA

A number of factors are intensifying the water cycle, but one of the most important is that warming temperatures raise the upper limit on the amount of moisture in the air. That increases the potential for more rain.

This aspect of climate change is confirmed across all of our lines of evidence: It is expected from basic physics, projected by computer models, and it already shows up in the observational data as a general increase of rainfall intensity with warming temperatures.

Understanding this and other changes in the water cycle is important for more than preparing for disasters. Water is an essential resource for all ecosystems and human societies, and particularly agriculture.

What does this mean for the future?

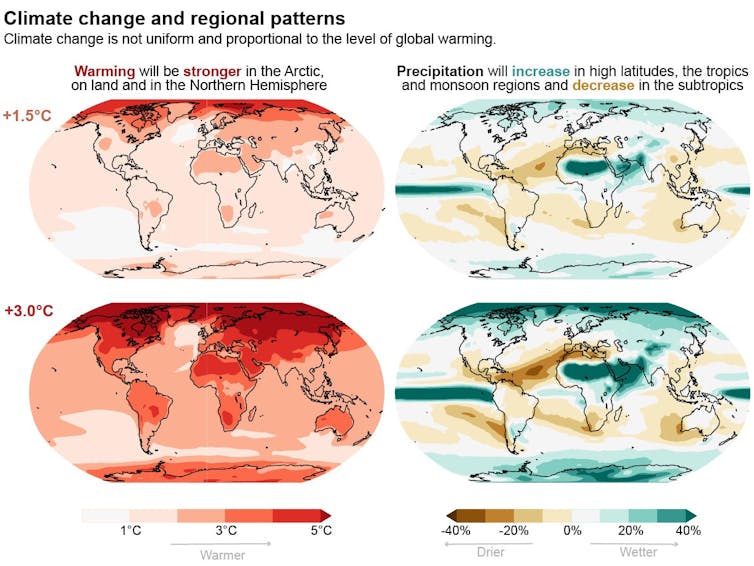

An intensifying water cycle means that both wet and dry extremes and the general variability of the water cycle will increase, although not uniformly around the globe.

Rainfall intensity is expected to increase for most land areas, but the largest increases in dryness are expected in the Mediterranean, southwestern South America and western North America.

IPCC Sixth Assessment Report

Globally, daily extreme precipitation events will likely intensify by about 7% for every 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) that global temperatures rise.

Many other important aspects of the water cycle will also change in addition to extremes as global temperatures increase, the report shows, including reductions in mountain glaciers, decreasing duration of seasonal snow cover, earlier snowmelt and contrasting changes in monsoon rains across different regions, which will impact the water resources of billions of people.

What can be done?

One common theme across these aspects of the water cycle is that higher greenhouse gas emissions lead to bigger impacts.

The IPCC does not make policy recommendations. Instead, it provides the scientific information needed to carefully evaluate policy choices. The results show what the implications of different choices are likely to be.

One thing the scientific evidence in the report clearly tells world leaders is that limiting global warming to the Paris Agreement target of 1.5 C (2.7 F) will require immediate, rapid and large-scale reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

Regardless of any specific target, it is clear that the severity of climate change impacts are closely linked to greenhouse gas emissions: Reducing emissions will reduce impacts. Every fraction of a degree matters.

[Understand new developments in science, health and technology, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s science newsletter.]![]()

Mathew Barlow is a professor of Climate Science at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.