This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis.

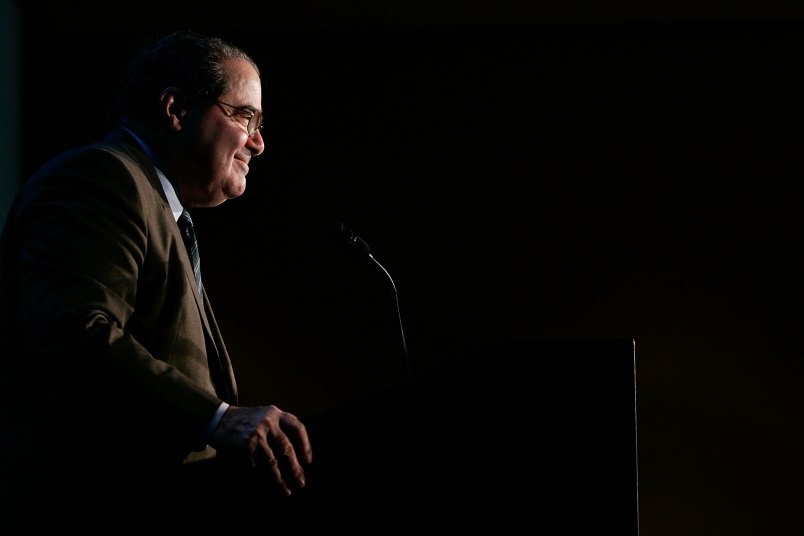

I wonder what Antonin Scalia would make of the Republican legislators in Maine who just voted to allow people to use religious exemptions to avoid vaccinations for their children. And how he would feel about Republican Senators who are now opposing a Trump judicial nominee because he advocated on behalf of a client against a farmer who didn’t want to host a same-sex wedding?

This position — in favor of strong religious exemptions to secular laws — is increasingly becoming the conservative party line. It’s a test of whether you support “religious freedom.”

Yet it was Scalia, the conservative hero, who, in 1990, ruled against Native Americans who used a religious freedom claim to justify using peyote, even though doing so violated anti-drug laws. Going down this path of allowing too many religious exemptions would, Scalia wrote, “lead towards anarchy.” We’d end up with “religious exemptions from civic obligations of almost every conceivable kind.”

Surprised that Scalia, the hero of conservatives, was railing against the overuse of religious exemptions? Back then, the judicial fault line tended to focus on whether you saw matters through the eyes of a religious minority or the majority. Conservatives bristled at the idea that claims of small groups of religious minorities should erode the rule of law or the majority culture.

What changed? Conservative Christians went from thinking of themselves as a Moral Majority to a Persecuted Minority. And with that, the politics of religious freedom got turned on its head.

Let’s review the history of what are now called “accommodation” cases — the instances when society decides to exempt a religious person from a secular law because it inadvertently infringes on their faith practice.

This concept — that religious freedom requires us to bend over backward to respect the sensitivities of the religious — is a relatively recent development in American history. At the founding of the country, Quakers and other pacifists were able to avoid military service and abjure swearing an oath, which also violated their religion. But, mostly, the courts took a consistent position: if the law is secular in its nature, and neutral in its intent, then religious people have to abide by it, even if their ability to practice is constrained. For instance, in 1878, Mormons argued that anti-polygamy laws infringed on their religious freedom because “plural marriage” was an article of faith. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled against them, saying that the Constitution provided freedom of belief, not freedom of actions.

Everything changed in 1943. The school board in Charleston, West Virginia was requiring kids to salute the American flag. It was not a law that picked on any particular religion. It was an entirely secular, neutral law. But ten-year-old Marie and eight-year-old Gathie Barnett refused to salute — because they were Jehovah’s Witnesses, and their religion taught that flag saluting was akin to idol worship. The Supreme Court agreed with the Witnesses. Justice Robert Jackson declared, “If there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.”

From then on, even if a law wasn’t intended to hurt a religion, it might still be viewed as unconstitutional if the harm it inflicted was significant or if the law’s secular purpose wasn’t important enough. In his dissent, Justice Felix Frankfurter prophesied that this new world would be fraught with constitutional danger. Religious minorities could end up with too many “new privileges.” The First Amendment, he wrote, “gave religious equality, not civil immunity.”

In 1963, the Court went even further. In Sherbert v Verner, it ruled that a South Carolina law that in effect pressured Seventh Day Adventists to work on Saturdays was unconstitutional. The Court said that a law can infringe upon someone’s religious practice only if there is a “compelling state interest” and no other regulation could be conjured to achieve that same goal. Otherwise, the state must accommodate the person’s religious practice.

Until this moment, religious freedom had been defined primarily as an absence of persecution and the separation of church and state. Now there was another element: the state had to bend over backward to avoid making a religious person choose between the law and his or her faith. The American model of religious freedom had become still more robust, still more sensitive to the needs of believers — and a lot more complex.

In 1990, in Employment Division v. Smith, the conservative majority of the Supreme Court decided to pull back on religious freedom rights. When a member of the Native American Church asked for exemption from an anti-drug law that banned the use of peyote even for a religious service, the Court said no. The lead voice in restricting religious freedom? Antonin Scalia. (Congress eventually overruled the court with the Religious Freedom Restoration Act — opening the doors for religious groups to make all of the religious freedom claims we see these days.)

Following along? So far, the liberals were trying to expand religious freedom protections and the conservatives wanted to restrain them. Scalia felt that religious minorities were getting too much clout relative to the Christian majority.

Recently, as Christians have increasingly seen themselves as a persecuted minority, they have been the ones requesting religious accommodations: The bakers who claimed that they should be exempted from anti-discrimination laws or the nuns who didn’t want their organization’s employees to be eligible for contraceptive coverage under the Affordable Care Act. In other words, the religious freedom arguments by conservatives that now cause liberals to roll their eyes were pioneered by progressives in earlier decades.

The conservative interest in deploying the formerly liberal religious freedom claims intensified after the Court declared same-sex marriage to be a Constitutional right. Religious conservatives are not crazy to think that, taken to its logical extreme, same-sex marriage rights could potentially undercut the religious freedom of traditional Christians. The U.S. government tried to take away the tax exempt status of Bob Jones University because it banned interracial dating. By that logic, couldn’t it decertify schools that opposed same-sex marriage?

But there are also signs that Scalia and Frankfurter’s worst nightmare could come true. We’re seeing religious exemption claims now applied in a wide range of situations. The Catholic Archdiocese of Milwaukee claimed that theReligious Freedom Restoration Act and the First Amendment protected it from liability claims by the victims of pedophile priests. The recent outbreaks of measles are at least partly attributable to too many parents claiming religious exemptions to avoid having their children vaccinated.

Timothy Anderson in 2015 claimed that his arrest for selling heroin violated his religious freedom because he had distributed the drug to “the sick, lost, blind, lame, deaf and dead members of God’s Kingdom.” The court rejected the claim on the grounds that the heroin recipients didn’t realize they were partaking because of their religion. In Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, a group of nuns sued a federal agency attempting to put a natural gas pipeline through their property, arguing that the move violated their religious freedom because “God calls humans to treasure land as a gift of beauty and sustenance.”

Perhaps the most dramatic case comes from Brooklyn, where some ultra-Orthodox Jews practice a ritual called metzitzah b’peh — in which, after an infant is circumcised, the religious leader who performs the procedure uses his mouth to suck blood from the baby’s penis. City officials believed that this was unhealthy, citing evidence that it spread herpes, even causing brain damage in a few cases. They required families to sign a consent form. The rabbis sued, saying the rule violated their religious freedom. “You may ask, ‘what’s the big deal?’” Rabbi Gedaliah Weinberger declared. “‘All they are asking for is a consent form.’ The problem is that it not only intrudes on our religious practice, but it intrudes on our religious decision making.”

Where is the right place to draw the line? I’m inclined to think we need to reserve religious exemptions for rare cases.

But these are hard dilemmas — which is the bigger point. We have come to think of these accommodation cases as the equivalent of earlier attacks on religious freedom — like the hanging of Quakers or the imprisonment of Baptists for practicing their faith. Far from it. These cases arise because society has decided to bend over backwards to be extra sensitive to the religious.

It’s a worthy effort — if we keep this in perspective. If the government sometimes decides not to provide special exemptions from religious law, that’s not an egregious attack on religious freedom. If we start thinking of religious freedom as a superpower that enables anyone to avoid a law they don’t like, then religious freedom itself will become a farce.

Steven Waldman is author of SACRED LIBERTY: America’s long, bloody and ongoing fight for religious freedom and co-founder of Report for America.

Correction: This article originally stated that Trump judicial nominee drew Republican opposition because he ruled against a farmer who wouldn’t host a same-sex wedding. In fact, Trump nominee Michael Bogren did not rule but signed a brief while defending the City of East Lansing, a client.