This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It was originally published at The Conversation.

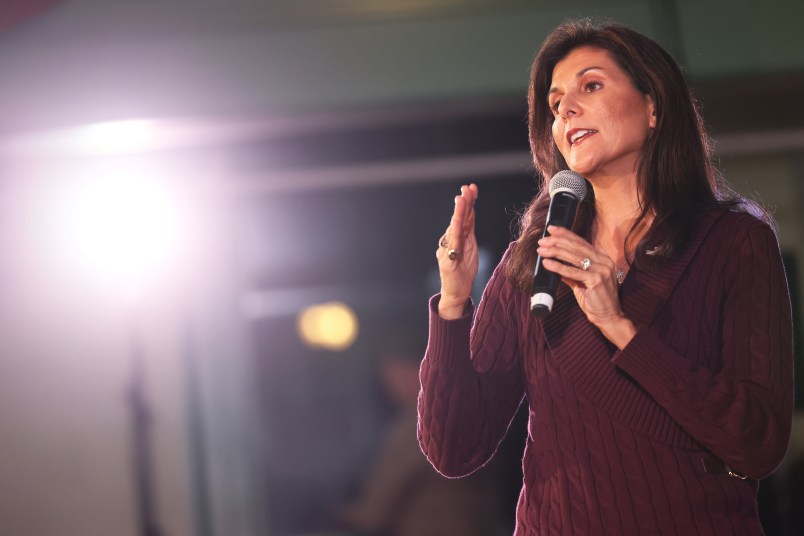

Former Republican South Carolina Governor and United Nations Ambassador Nikki Haley launched her bid for president recently in a video that began by describing the racial division that marked her small hometown of Bamberg, South Carolina.

Meanwhile, another presumptive GOP candidate, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, has continued his crusade against “woke ideology,” most recently on a tour of Pennsylvania, New York and Illinois, presenting himself as a defender of law and order.

Taken together, these events present a fundamental question about the future of the Republican Party.

Does it continue to move rightward, exciting its base by stoking white racial grievance?

Or does it pursue a multiracial strategy that can expand the party’s reach?

Recent trends in the GOP suggest that it wants to do both — and that indeed the two strategies are not so much at odds as it might appear.

Right-wing candidates of color on the rise

In a striking development, Michigan Republicans selected in February 2023 a Christian nationalist and election denier as chair of the state party.

This rightward shift of the party is not itself surprising.

What’s striking is that Kristina Karamo, a Black woman, was elected over a white male candidate who also had Trump’s endorsement.

The same voters who elevated Karamo also cheered Trump’s supercharged racist rhetoric against Black people, immigrants, Mexicans, Muslims and nonwhite countries more generally during his campaigns and presidency.

And yet Karamo is hardly an anomaly.

While the party has made no substantive changes or moderation to its politics or policies around long-standing racial justice issues, it is slowly but steadily growing more racially diverse in its grassroots base, elected officials and opinion leaders.

In the 2022 midterm elections, for instance, a new Republican majority in the House of Representatives was secured by a number of Black and Latino candidates who ran strong races while avoiding the extremist label.

Though the U.S. Senate race in Georgia saw Black GOP candidate Herschel Walker lose to Democratic incumbent Sen. Raphael Warnock, there were seven victorious Black or Latino Republican newcomers to the House, four of whom won seats previously held by Democrats.

Most notable among the growing number of Republican lawmakers of color is Byron Donalds, a two-term representative from Florida. He was nominated by a GOP colleague to serve as speaker of the House during the chaotic several days and 15 rounds of voting that preceded Kevin McCarthy’s election to that role.

Relatively young and new to national politics, these GOP politicians are largely aligned with Trump on substantive issues.

What’s more, none downplayed the issue of race, but rather are using their biographies and experiences of racial discrimination to legitimize their conservative bona fides.

The GOP race card

In Haley’s speech, she decried a national “self-loathing” that is “more dangerous than any pandemic” in regard to the country’s racial history.

“Every day we’re told America is flawed, rotten and full of hate,” Haley said. “Joe and Kamala even say America’s racist. Nothing could be further from the truth. Take it from me, the first female minority governor in history.”

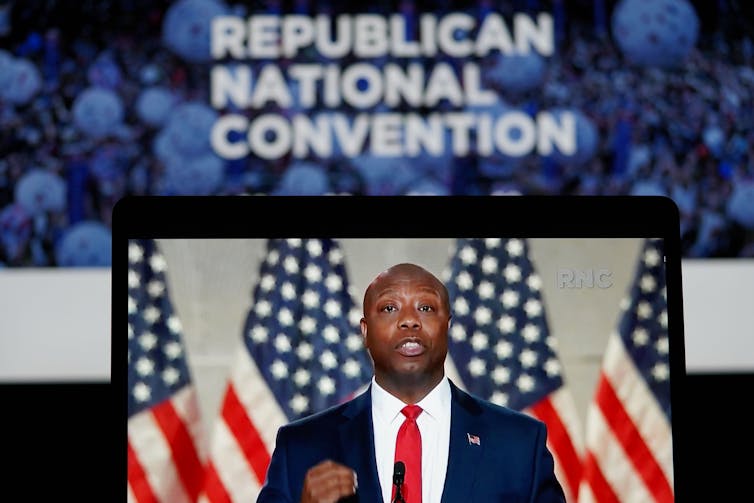

Meanwhile, African American Republican Sen. Tim Scott also appears close to entering the race for the GOP presidential nomination.

Like Haley, Scott uses his own biography to undercut Democratic claims to represent people of color.

“For those of you on the left,” Scott said in a February 2023 speech in Iowa, “You can call me a prop, you can call me a token, you can call me the n-word. You can question my blackness. You can even call me ‘Uncle Tim.’ Just understand, your words are no match for my evidence. … The truth of my life disproves your lies.”

Neither Haley nor Scott is running as the colorblind conservatives of years past.

Both embrace their racial identities and talk openly about racial issues and politics, with little damage to their electoral prospects. Both have won large pluralities of conservative white voters in their states.

But the path ahead is mired with challenges and vexing contradictions.

Will a national GOP electorate that has cheered on a host of demeaning attacks on minority groups from its leadership support the candidacies of figures like Haley and Scott?

Colorblind conservative voters?

Polls show that roughly 70% of Republicans believe the “great replacement theory,” a baseless belief that the Democratic Party is attempting to replace the white electorate in the United States with nonwhite immigrants.

Those same conservative voters are consistently motivated by white racial grievance in issues concerning public education, law enforcement, voting rights and affirmative action.

Yet studies also suggest that white conservatives will indeed support candidates of color, not out of a commitment to racial justice or even representation, but because they see it as a way to advance partisan and ideological interests.

A 2015 article in Public Opinion Quarterly presented data showing that these voters “are either more supportive of minority Republicans or just as likely to vote for a minority as they are a white Republican.”

Similarly, a 2021 study showed that under the right conditions, “racially resentful [white] voters prefer to vote for a Black candidate over a white competitor.”

These studies suggest that the Republican electorate is fertile ground for certain candidates of color who can effectively link their biographies to stock conservative accounts of individual uplift, opposition to social welfare — and the demonization of liberalism and liberals.

Voters of color matter

How about voters of color?

Will they continue to view the GOP as a racist party inhospitable to their interests?

Exit polls after the 2020 election showed that Trump increased his gains among all groups of minority voters in comparison to 2016, capturing 1 in 4 voters of color nationally.

He won the votes of nearly 1 in 5 Black men, and roughly one-third of the Asian American and Latino electorate.

While Republican strategists and candidates are attempting to creatively reframe the relationship of race to modern-day conservatism, none have articulated ideas or policies that directly confront the issues facing a majority of African Americans and other people of color.

Those issues include a predatory criminal justice system, the evisceration of funding for health care and education, the existential threats of climate change and attacks against multiracial democracy.

It’s unclear whether those issues will find a way into conservative talking points.

What is clear is that political identities determine political interests — not the other way around.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.