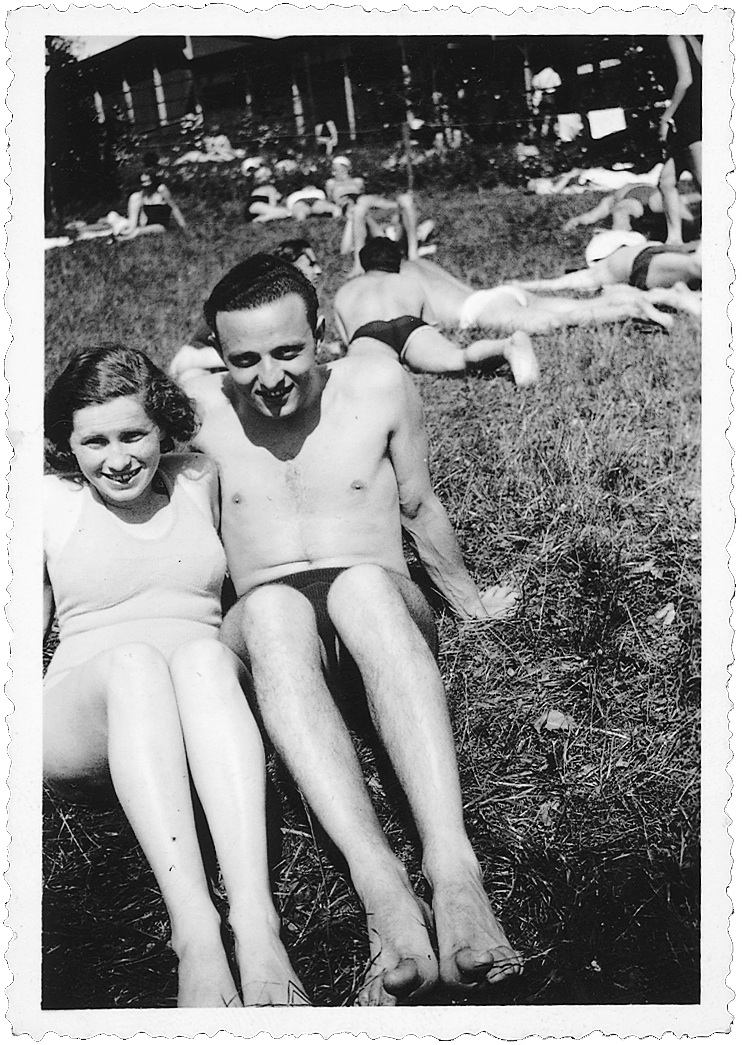

My grandfather Karl escaped from Nazi occupied Vienna in the fall of 1938. By 1940, everyone he had ever known in that city was either on the run from, or scrambling to leave, Europe. I found a collection of letters that documented that desperation. Among them, there were dozens of missives from his lover, Valerie – Valy – Scheftel. Of all his friends, no one was more intense in her efforts to escape. By 1940 she, too, was on the run – but she had run deeper into the Reich, rather than out. She moved to Berlin sometime in the winter of 1938/1939 and in this series of letters I found, excerpted here, I discovered that even those around her in the heart of Hitler’s Germany were lobbying my grandfather to help her. But as you will see from primary documents unearthed at the University of Minnesota’s Immigration Research Center archives, my grandfather was in no monetary position to help anyone.

Valy knew others were getting their loved ones out, and my grandfather knew, and that knowledge hangs heavy in letters. The anguish was already intolerable. What had they done that he hadn’t? What had they accomplished that he could not?

Valy knew others were getting their loved ones out, and my grandfather knew, and that knowledge hangs heavy in letters. The anguish was already intolerable. What had they done that he hadn’t? What had they accomplished that he could not?

In the meantime, bits and pieces of the degradation and humiliation now defining life in Germany were trickling out, exposing Karl to some of the horror. Even strangers implore him to help Valy.

February 24, 1940

Dear Dr. Wildman,

I do not know whether Dr. Valy Scheftel in her letters to you ever mentioned my name. Until March of 1939 I was a rabbi in Berlin, where the Gestapo had tasked me with the care of the Jews in the occupied Sudetenland. It was in this context that I met Dr. Scheftel in Troppau.

I am writing to you in order to inquire whether and to what extent you may be in a position to do anything for the emigration of Dr. Scheftel, and possibly also her mother. I do know that you sent affidavits about a year ago that were submitted to the consulate in Prague. In the best case scenario, the waiting period for Valy would be at least two years and even longer for her mother. Before my own emigration, I tried to do something for the two women, at least economically. As you surely know, V. has been working in a children’s home of the Reichsvertretung. It was my hope that this work would at least feed the two women until they can come here.

The events that unfolded during the past weeks, however, and especially the beginning deportation of the Jews . . . let me fear the worst. I would be only too happy to help them to immigrate to an interim country, where they could wait until their US number gets called up. Only a few weeks ago, my parents-in-law immigrated to Chile. At the moment I am working on the emigration of other relatives whom Valy often sees, from Berlin to Chile. (This is the only country for which it was possible to find visas for the past several weeks. Brazilian visas, for example, are no longer affordable, at least for my means.) Do you think that you or others might be able to do the same for Valy and her mother? A Chilean visa for one person cost me US $150.00, and a confidential source has written to me that additional visas would cost about the same amount. While the visas appear legitimate, they seem to have been issued illegally. In any event, they enable immigration to Chile, as the case of my in-laws, who arrived in Chile on January 3rd, proves. My confidante, a former physician from Breslau, who now is in Santiago, is absolutely trustworthy.

I beg you not to misunderstand me. I only write to you because of my concern as a friend for Dr. Scheftel, who again wrote to me a few days ago. I would be most grateful if you could write to me soon what your position on this issue is, and, above all—something I am unable to decide on my own—whether you consider this solution, interim country with further immigration to the USA, as feasible, as far as Valy is concerned. As far as I know her and her mother, I believe that they would be capable of feeding themselves in Chile until they can come here. And, although it may be difficult in Chile, a hard life in physical safety is preferable to an easier life in constant danger.

With kind regards,

Sincerely,

Alfred Jospe

(translated by Ulrike Wiesner from the German)

“The events that unfolded during the past weeks, however, and especially the beginning deportation of the Jews . . . let me fear the worst.” Jospe is referring to the deportation of the Jews of Stettin, which took place earlier that month. Stettin — now known as Szczecin — is a Baltic seaport; in early 1940, the Germans violent expulsed Stettin’s Jews. They were rounded up, brutally, aggressively, robbed of their possessions, and then sent on to Lublin, Poland, to “clean” the area, to make room for the Volksdeutschen — the ethnic Germans — who wanted their homes. The entire community, from children as young as two to octogenarians, were roused from their homes, some forced into a former mortuary under conditions so crowded many died there, on the spot, foreshadowing what would come for the rest of Europe’s Jews.

But unlike what happened later, this deportation was handled so baldly that Jews across the Reich learned of it and panicked. Even the foreign press got wind of it. On February 19, 1940, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency reported from Paris that fifteen hundred “men, women, children and even the inmates of the local Jewish home for the aged were piled on a cattle train to be shipped to an unknown destination. . . . Those too old or sick to walk had to be carried to the train by others. . . . Nazi storm troopers visited Jewish homes on two successive nights, told the occupants to prepare to leave, forced them to file inventories of their possessions and then confiscated all valuables after requiring them to sign statements renouncing this property. The expulsion took place at three o’clock on a bitterly cold morning. Two storm troopers called at every Jewish house to see that the deportees took no silverware or other valuables. They were permitted to take only a small valise each containing necessary articles. Bank accounts were confiscated.” A month later, more news trickled out: the Jews of Stettin were dying, in droves.

Foreign diplomats clamored to know what was happening. Germans grumbled to each other in official documents that the United States would get involved if they weren’t more careful. They were anxious to keep neutral America — and Roosevelt — disinterested.

So Jospe knows this — and he assumes my grandfather does as well. But — how awful — the hundred fifty dollars he proposes for a visa was an inconceivably large amount of money for Karl. Astronomical. Three hundred dollars to rescue the two women wasn’t simply large, it was nearly the entire amount that the National Committee for Resettlement of Foreign Physicians would lend my grandfather later that spring to start his career. It was a fantasy sum.

So when Jospe says the Brazilian visas are too high, but Chile is accessible, he doesn’t know that what he is asking is completely out of reach, and not simply because none of these schemes was fail-safe. These illegal visas — if discovered as false — could simply lose all value on a moment’s notice, leaving the women stranded, and any funds scraped together for them would disappear.

And yet despite this, Jospe’s admonition seems to have spurred Valy’s uncle Julius, already here in America, and my grandfather into some kind of action:

New York, March 25, 1940

Dear Karl,

Enclosed is a letter from Dr. J. . . . Before I answer the letter, I want to write you a few lines, make my opinion known to you, and ask you to what extent you could be (materially) helpful to me, that is, what sum of money you could scrape up. Of course, it would be considered a loan to me. Forgive me for bothering you with such matters. The possibility that both women could be rescued sounds much too good to be true. It goes without saying that dear Valy would not leave without her mother, and I think that things mustn’t come to naught over the sum of $300. I could round up $50 at most and pledge to pay back $20 a month over the course of six months. The remainder I would repay later, when I’m able.

–I would be very happy to be able to write and tell Dr. J. to initiate the necessary steps. I anticipate that the relief committee [Hilfskom.] will take care of the tickets for the ship (Dr. J.’s intervention regarding the tickets will surely be successful). Please write me immediately so that we don’t lose any time, and I would be very grateful to you for a reply in the affirmative.. . . .

Warmest regards,

Julius

(translated by Kathleen Luft from the German)

Reading this, I am horrified. A three-hundred-dollar missed opportunity. In February 1940, Karl was mired in debt and taking on more debt each month. An internal memorandum of the National Refugee Service, written in June 1940 and held in the files at the University of Minnesota, discussed the case of the Wildman family at large: he could not help with the upkeep of his mother, let alone with anyone else.

The following information refers to our telephone conversation of 6/17, in connection with Dr. Chayim Wildman [sic]…Mr. [sic] Wildman’s mother Sara, 75 years old, arrived in New York 9/10/38. She lived with her brother, Sam Feldschuh, an upholstery salesman…Mr. Sam earns $15 a week and therefore, when he was unable to continue maintaining his sister, she went to live with her daughter Celia F. She sold her remaining jewels for $60 and thus paid for her upkeep for sometime. When this was exhausted she applied to us for help on 2/2/340.

Financial assistance has been given since 4/12 at the rate of $23 a month. I was not aware of the fact that Chayim [sic] earned anything at all, or I should have gone into the possibility of his helping his mother to some extent. His sister, Celia, tells me Chayim is not able to contribute anything at all….

There was no money for visas to Chile. There was nearly nothing to eat. He is embarrassed. I find a draft of a letter he wrote to a friend dated December 14, 1940, months later. “I regret to have to tell you that I am not getting on so ‘very’ well as you seem to believe. I am probably doing much better than anybody else who has been practicing for 6 weeks, but it is still far from being satisfactory.” He is not yet in control of this new country — him! The one who mastered everything, the one for whom everything came easily — languages, affidavits, visas, jobs. Here he was failing Valy, not by his own accord, but what did that matter? He couldn’t win. He had nothing to offer her beyond the affidavits he had already issued, the affidavits that would soon wither and expire. And here he was, shamed by outsiders, by Valy’s Uncle Julius, by this stranger, Rabbi Jospe — all of them underlining for him that he is failing her. It is simply awful. It is unfair. He seems unwilling to let that be the case, and yet neither can he realistically offer much in the way of material support.

This excerpt is adapted from Paper Love: Searching for the Girl My Grandfather Left Behind by Sarah Wildman. This excerpt was reprinted by arrangement with Riverhead Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC.

Sarah Wildman has made a name for herself writing for places like The New York Times, The Nation, The New Yorker, and the New Republic on subjects ranging from politics and culture, to where history and memory intersect with the present day.