This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis.

In 1991 Los Angeles Times Pulitzer Prize-winning syndicated sports columnist Jim Murray called Milt Campbell “as magnificent an athlete as anyone who came before or after him.” Nine years later, the legendary Olympic filmmaker Bud Greenspan said that Campbell was “the greatest athlete who ever lived.”

But if you don’t recognize the name, you’re not alone.

Campbell won the silver medal in the decathlon at the 1952 Olympic games in Helsinki, Finland and secured the gold medal four years later in Melbourne, Australia — the first African American to prevail in that Olympic sport. But he lived most of his post-Olympic life in relative obscurity, especially compared with other Olympic decathlon winners who translated their athletic success into visible and lucrative careers in sports and entertainment.

Jim Thorpe became the first Olympic celebrity when he won the decathlon in the 1912 summer Olympics in Stockholm. When awarding Thorpe his prize, King Gustav said, “You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world.” The description stuck. Every decathlon gold medalist since has worn that label.

Participants compete in ten events over a grueling two days, including the pole vault, long jump, high jump, shot put, discus, javelin, 100-meter dash, 400-meter dash, 110-meter hurdles, and 1,500-meter run. Decathletes may not be the best in the world at any single event, but must display a remarkable diversity of athletic skills (running, jumping, and throwing) that require speed, strength, agility, spring and endurance.

During the Cold War, whichever country could claim the “world’s greatest athlete” had bragging rights that went beyond the world of sports.

Between 1948 and 1976, Americans won six out of eight decathlon gold medals. Of those winners, all but one became household names and global celebrities, garnering lucrative commercial endorsement contracts and even acting roles. Bob Mathias (who won the gold in 1948 and 1952) appeared in several movies and TV shows before serving as a U.S. congressman from California for four terms. Rafer Johnson (1960) became a popular sportscaster, appeared in a dozen Hollywood films, and was a confidant of the Kennedy family. (In 1968, standing on the podium behind Senator Robert Kennedy at the celebration of his victory in the California presidential primary, Johnson wrestled the gun from Kennedy’s assassin at the Ambassador Hotel.)

Bill Toomey (1968) turned his Olympic celebrity into a career as a TV broadcaster, marketing consultant, and head track and field coach at the University of California at Irvine. Bruce Jenner (1976) translated his gold medal victory in the Montreal Olympics into a money-making career in television, films, auto racing, business, as a Playgirl cover model, and, in 2007, as part of the reality television series Keeping Up with the Kardashians with his wife Kris Kardashian. He achieved another kind of notoriety in 2015 when he publicly came out as a trans woman and became known as Caitlin Jenner. Jenner is currently running for governor of California as member of the Republican Party.

An American didn’t win the Olympic decathlon gold medal again until Dan O’Brien in 1996, followed by Bryan Clay in 2008, and Ashton Eaton, in 2012 and 2016. Each of them converted their Olympic fame into successful careers in sports, business, and public service.

Soon after his Olympic success, however, Campbell almost disappeared from public attention.

Campbell was an outstanding football player and a national hurdles champion at Plainfield High School in New Jersey. But he was an all-around outstanding athlete. When a fellow PHS student told Campbell that Black people lacked the aptitude for swimming, he took up the sport and became the swim team’s top sprinter and an All-American swimmer.

During his junior year in high school, Campbell entered the Olympics decathlon trials despite having never participated in the ten-sport competition before. He won the 1952 national championship and then flew to Helsinki for the Olympics, where the 18-year old Campbell finished second to Mathias. That year, Track and Field News named Campbell “High School Athlete of the Year.”

After graduating from high school in 1953, Campbell attended Indiana University on a football scholarship. In his two years at IU, he won the NCAA and AAU high hurdles championships and played defensive back and halfback on the football team. When he occasionally tried his hand at judo, karate, bowling, wrestling, and tennis, he beat all comers.

He left IU in 1955 and joined the Navy. While stationed in San Diego, he kept up his training for his next shot at the Olympics.

He won the decathlon gold medal in 1956, setting an Olympic record of 7,937 points for the ten events. UCLA’s Rafer Johnson won the silver medal that year. The Soviet Union’s Vasily Kuznetsov earned the bonze.

Despite his victory in Melbourne, no companies asked Campbell to make commercials or become a spokesman. No Hollywood producers asked him to do a screen test for a movie.

He continued to compete in track and field, setting world records in the indoor 60-yard high hurdles and the outdoor 120 high hurdles in 1957. (He remains the only Olympic decathlon gold medalist to have held a world record in an individual event.)

At the time, amateur athletes were not permitted to get paid for participation in sports, and Campbell needed to make a living. He joined the Cleveland Browns, which had drafted the 6-foot-three-inch 220-pound halfback. He spent the season backing up another rookie, Jim Brown, who went on to become one of the greatest running backs in NFL history. Campbell saw little playing time, rushing for 23 yards on seven carries.

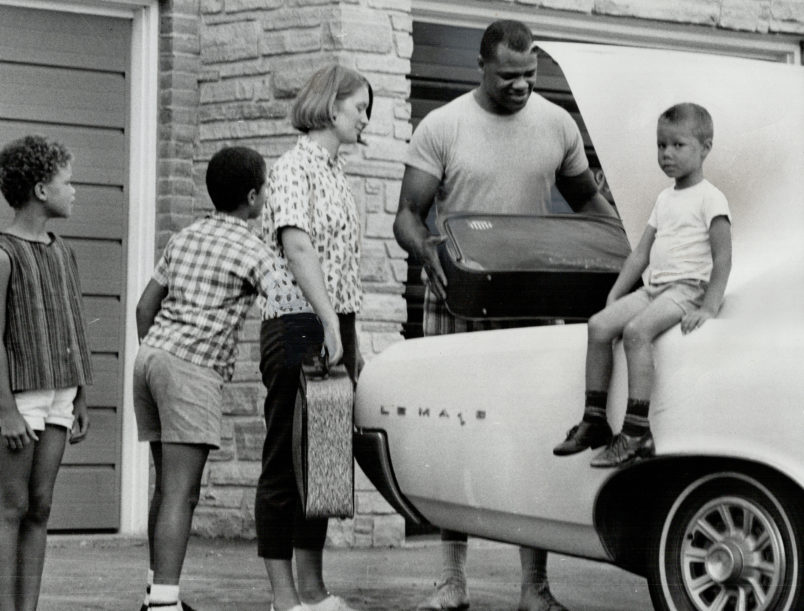

Before the start of the 1958 season, Browns coach Paul Brown called Campbell into his office. He asked Campbell why he had married a white woman (Barbara Mount) during the off-season. Campbell told Brown it was none of his business, he later recounted. The Browns cut Campbell the next day.

According to Campbell, no other NFL team would hire him. “I was blacklisted because I had an interracial marriage,” he once said.

Instead, he went to Canada, playing professional football for the Hamilton Tiger-Cats, Montreal Alouettes, and Toronto Argonauts until 1964, with much less pay and visibility than if he’d remained in the NFL.

After race riots exploded in Newark and Plainfield in 1967, Campbell returned to New Jersey. He co-founded a community center and alternative school in Newark, the Chad School, that focused on Black history and culture, and earned a modest living as a motivational speaker.

The sports world continued to snub Campbell. In 1983, the U.S. Olympic Committee announced the first 20 athletes to be inducted into its Hall of Fame. They selected Mathias and Johnson, but not Campbell, who wasn’t added until 1992. The National Track and Field Hall of Fame opened in 1974, but Campbell wasn’t inducted until 1989. The International Swimming Hall of Fame inducted its first 21 members in 1965, but waited until 2012 to include Campbell. He also wasn’t inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame until June 2012, five months before he died of cancer at 78.

He lived most of his post-Olympic life outside the limelight, especially compared with the other decathletes who had earned the accolade as “world’s greatest athlete.”

Why?

“America wasn’t ready for a Black man to be the best

athlete in the world,” Campbell insisted. While other athletes turned their gold medal into gold, “I got absolutely nothing.”

“I’ve paid my dues,” he said on another occasion, “but the advertising and commercial worlds don’t call me.”

Some would argue that African American Rafer Johnson’s later fame and fortune after he won the decathlon gold medal in 1960 undermines Campbell’s point, but the timing is important.

The 1960 Olympics, held in Rome, were the first to be televised in the United States. That year, and ever since, the Olympic star athletes became household names.

Campbell won his gold medal before the major upsurge of civil rights activism. True, Rosa Parks sparked the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955, but it wasn’t until the lunch counter sit-ins began in February 1960 (and the Freedom Rides the following year) that the freedom struggle became part of America’s daily news diet. Johnson’s 1960 gold medal was viewed as a civil rights victory as well as an athletic one.

Moreover, the Cold War provided a backdrop to the 1960 games. News coverage focused on the number of medals — particularly gold medals — won by Americans and Russians. The athletes themselves were often friendly rivals, but the politicians and journalists viewed them as warriors in a global battle for hearts and minds. This was particularly the case with the decathlon, and the competition between Johnson and his Russian counterpart, Kuznetsov. To accentuate the struggle, Johnson was selected as the flag bearer for the United States at the opening ceremony. The two athletes had competed against each other in different contests around the world, but the Olympics was center stage. Johnson’s gold medal was viewed as a victory in the Cold War. (Kuznetsov captured the bronze medal, behind silver medal winner Yang Chuan-Kwang of Taiwan, who had trained at UCLA with Johnson.)

Another factor: Campbell went to college in Indiana, outside the media limelight. Johnson, who grew up in California, attended UCLA in Los Angeles, where Hollywood reached out to him following his Olympic victory.

Campbell had little mentoring in high school or college as either an athlete or student. He competed in his first decathlon at the 1952 Olympic trials. In contrast, Johnson was carefully nurtured as a decathlete in high school and carefully mentored at UCLA. Campbell was one of the few Black students at Indiana University and was treated more as an athlete than a student, recruited as much for his prowess in football (which attracted more fans and money) than track and field. He dropped out before earning a degree. Johnson picked UCLA because of its history of recruiting and encouraging Black students, including Jackie Robinson. His fellow students elected him UCLA’s student body president and he completed his undergraduate degree.

Campbell was in high school when he won the silver medal and in the Navy when he won the gold. Johnson was a sophomore at UCLA when he earned his silver medal at the Melbourne game. He missed two seasons due to injury so he was still a student at UCLA, under the careful watch of world-class coaches, when he was training for the 1960 Olympics, when he won the gold.

Both Campbell and Johnson grew up poor, but Johnson had Hollywood good looks and a middle-class demeanor, while racist stereotypes consigned Campbell as a product of the New Jersey ghetto.

Campbell was also outspoken about racism and bitter about his mistreatment, qualities that may have made white people uncomfortable and hampered his post-Olympic success.

Both athletes were involved in public service, but while Johnson was part of the glamorous Kennedy world, Campbell worked in Newark and Plainfield, mentoring Black students.

This year, countries will provide huge rewards for their Olympic medal winners, many of whom will additionally garner lucrative commercial endorsements. Sports pundits and broadcasters have already described Canada’s Damian Warner, who won the decathlon gold medal on Thursday, as the “world’s greatest athlete.”

As they describe Warner’s accomplishments, he should be put in the same company as other outstanding decathletes. The odds are pretty good that the name Milt Campbell won’t be part of that conversation. That’s a tragedy.

Peter Dreier is professor of politics at Occidental College and author of “The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame.”