This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. The author is a senior editor at Worth magazine.

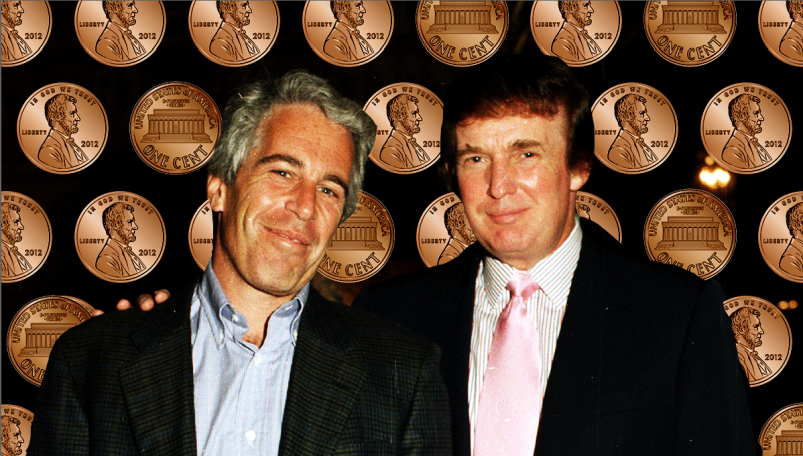

Accused child sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein and his fair-weather friend Donald Trump have a lot in common.

Both of these men have been accused of various sex crimes and other gross misbehavior. They both went to the same parties. And they both have likely lied to the public — at the very least, they’ve failed to disavow claims — about being billionaires. They have relied on the New York City business press to propagate this myth for them. One fake billionaire is a surprise. Two, though, is a pattern.

What’s going on? Why have so many news outlets indicated these men are billionaires, a term which carries with it an air of real-world power, might and accomplishment, if it’s unclear that they are?

Billionaires — like them or not — are the new aristocrats of the world; it is a title that must literally be earned (or inherited, as the case may be). Although Epstein’s worth at least $500 million, there’s little evidence that he ever broke ten figures (Forbes, to its credit, does not include him in its ranking of billionaires). Indeed, his own attorneys told a Manhattan judge in a bail hearing that his assets only totaled $559 million, almost a third of which is tied up in illiquid real estate (more details are expected in the coming days).

Most of Epstein’s money seems to have been earned managing other wealthy individuals’ fortunes, although Epstein’s only known client was Victoria’s Secret founder Les Wexner, and that relationship seems to have ended years ago. Epstein’s firm was registered in the Virgin Islands and generated no known public reports. Some have speculated that in reality he was running a Ponzi scheme, a theory buoyed by the fact that he spent his early years in finance working for Steven Hoffenberg who, in the early 1990s, was imprisoned for running a $450 million Ponzi scheme. Adding to the fishiness of Epstein’s fortune, in 2003 Vanity Fair reporter Vicky Ward quoted various sources who said most of his business essentially consisted of high end bounty hunting — recovering stolen funds for very rich people.

Trump’s finances are similarly murky — we don’t know what the President is worth. But we do know that he lies about his wealth, such as in a reported incident when he was applying for a loan from Deutsche Bank. He said he was worth over $3 billion, while the bank’s employees concluded he was worth only $788 million.

But $788 million is still a lot. Given that, what value is there in the press naming pretenders such as Epstein and Trump to the rarified ranks of the billionaires? And why do they stay silent about the inflation of their net worth?

By way of explanation, I’d like to regale you with Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Emperor’s New Clothes.” In this fairy tale, the ruler of the land is such an inveterate narcissist that he forsakes traditional imperial tasks, such as reviewing his soldiers, except when he has a new outfit to show off. This potentate loves clothes.

One day, “two swindlers” come along and tell the emperor that they are the most skilled weavers in the world. They tell the king that they are so skilled, in fact, that “this cloth had a wonderful way of becoming invisible to anyone who was unfit for his office, or who was unusually stupid.”

Most readers are probably familiar with the rest. The scammers weave and weave their magical fabric. The emperor is interested in their progress but sends a trusted advisor to report back. He, of course, does not see anything, because there is nothing to be seen. “Can it be that I’m a fool?” the old man asks himself. “I’d have never guessed it, and not a soul must know. Am I unfit to be minister? It would never do to let on that I can’t see the cloth.”

Instead, the old advisor tells the swindlers that the fabric is just beautiful, “enchanting,” in fact. They continue to “explain the intricate pattern” and name all the colors, so as to give the old man plenty to report back. Indeed, he returns and dutifully parrots the same to the emperor. The pattern repeats itself, and eventually the emperor himself, rather than admit that he cannot see the fabric and thus would be unworthy to rule, likewise engages in the charade.

The circle is complete — the swindlers say the fabric is beautiful, the emperor, a pure narcissist, can’t admit that he isn’t fit for office, and his courtiers are so cowed that they can’t provide a reality check to the potentate. Everybody is better off engaging in the lie. This continues until the Emperor dons the clothes that do not exist and parades through the street accompanied by his men. The people praise the clothes until a child finally says the obvious: “But he hasn’t got anything on.”

The reality is that estimations of net worth — the wealth that an individual has accrued — are more an art than a science in many cases. An individual’s net worth is ordinarily a private matter, and the wealthier people become, the more private they tend to be. Calculating net worth often requires back of the envelope math using public information — publicized salaries, bonuses, property values and art acquisitions, for instance — that does not necessarily account for invisible changes in asset values, debts, assets owned by family members, subjective valuations of things such as personal brands, or assets squirreled away in shell companies. Under- and over-estimation are always a risk. Yet this scenario at least assumes that you’re doing your homework. Less careful journalists may simply throw in the world “billionaire” here or there in a poetic attempt at saying “really, really rich.” This is certainly lazy and surely common.

And I’ll let you in on a dirty secret: Coverage of the wealthy, like all journalism, depends on maintaining a certain level of access to your subjects. Unfortunately, it’s easy enough for the maintenance of access to turn into the stroking of egos. In the case of Epstein, it’s not hard to see how a very wealthy man, who says that his firm only takes billionaires as clients, becomes a billionaire in the words of journalists interested in accessing his voluminous network that includes everyone from Donald Trump to Bill Clinton to Alan Dershowitz.

In the case of Donald Trump, his entire brand and business was built on projecting the image of being really, really rich. “Centimillionaire Donald Trump” doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue. Actively promoting the idea that he was in the Three Comma Club was good for Trump’s business, and Trump was always good copy for reporters covering New York society. For many years, declaring Trump a billionaire was a win-win: he’d give out quotes like candy in exchange for a little shine.

In both cases, Epstein’s and Trump’s networks, including everyone from Harvard economists to prominent politicians, lent them credibility. They must be the real deal, else why would all these important, connected, wealthy people hover around them so?

Put simply, saying that Donald Trump and Epstein were like the emperor — naked, possibly deluded narcissists — brought little gain for most observers, yet carried with it the risk of becoming enemies to powerful, potentially litigious men with lots of friends.

For me, there’s another question: Now that they’re exposed, why don’t men like Trump and Epstein at least come clean about their inflated wealth? The last lines of the fairy tale include a clue: “’But he hasn’t got anything on!’ the whole town cried out at last. The Emperor shivered, for he suspected they were right. But he thought, ‘This procession has got to go on.’ So he walked more proudly than ever, as his noblemen held high the train that wasn’t there at all.’”

The key, I think, is pride. Wealth, power and manhood, particularly for those most brittle and twisted souls, are inextricably linked. Were they to admit that they’re not actually quite so rich — that much of the press was getting it wrong — they would puncture the illusion that both men used to buoy their career. What else would they have to admit? That they prey on the weak? That they live lives without goodness? This realization could be a turning point. But truth be told, it’s scary, weak and humbling to be naked. And if everyone is willing to buy into the lie, why bother?

Benjamin Reeves is senior editor, special projects at Worth magazine where he covers wealth, finance and power and edits the publication’s annual Power 100 ranking. He also hosts Worth’s Power & Impact podcast, contributes to Columbia Business School’s thought leadership publications, and is a former foreign correspondent in Latin America. He is a graduate of Knox College and earned an MA in Experimental Humanities from NYU and is an MFA candidate in screenwriting at the Feirstein Graduate School of Cinema at Brooklyn College. Follow him on twitter: @bpreeves.