This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It first appeared at The Conversation.

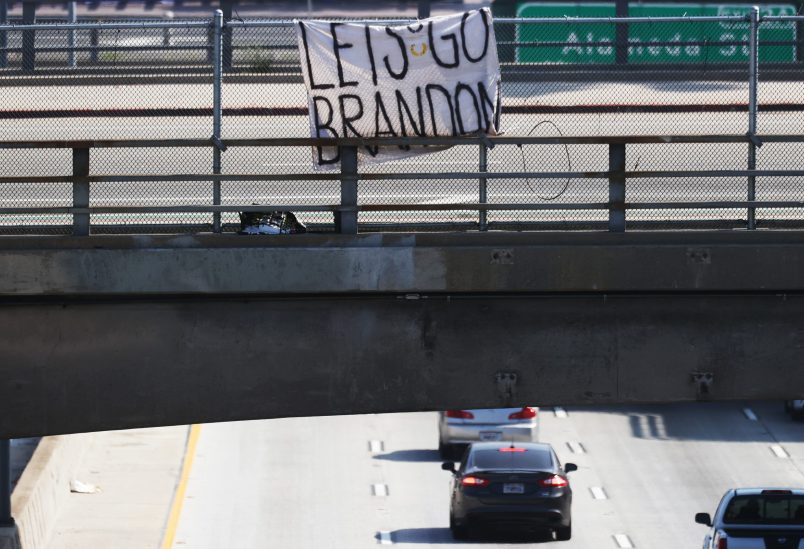

During an interview with NASCAR driver Brandon Brown on Oct. 2, 2021, NBC sportscaster Kelli Stavast made a curious observation. She reported that Talladega Superspeedway spectators were chanting “Let’s go Brandon” to celebrate the racing driver’s first Xfinity Series win.

In reality, however, the crowd was shouting a very different phrase: “F–k Joe Biden,” a taunt that had become popular at college football games earlier in the fall.

The deliberate misinterpretation of the crowd’s chant was a deft bit of verbal legerdemain on Stavast’s part. Although she hasn’t publicly explained herself, it seems likely that she was defusing the obscene, politically charged epithet so as not to offend her network’s sponsors and viewers.

The phrase, however, quickly took on a life of its own. It provides an interesting example of how language and politics make strange bedfellows – for conservatives and liberals alike.

Making the unacceptable acceptable

Judging from recordings of the interview available online, it is unlikely that Stavast misheard the crowd’s chant. If she had, her error would be classified as a mondegreen, which is a slip of the ear. Examples include mishearing Elton John’s “Tiny Dancer” as “Hold me closer, Tony Danza.”

The enthusiastic adoption of the phrase by President Joe Biden’s detractors suggests that “Let’s go Brandon” is best described as a minced oath. These are euphemisms used in place of a taboo or blasphemous expression.

Such oaths have a long history in English; an early example is “Zounds,” a euphemism for “God’s wounds” that started being used around 1600. “Darn” in place of “damn” emerged by 1800, while “heck” and “shoot” became popularized by the 1870s and the 1930s, respectively.

Minced oaths have also been used extensively on television. In these cases, the goal is to circumvent constraints imposed by a network’s standards and practices, with certain terms used by characters in place of profane language, whether it’s “frack” in “Battlestar Galactica, ”fork“ in “The Good Place” or “fudge” in “South Park.” Even Homer Simpson’s oft-repeated cry of dismay – “D’oh!” – is a minced oath for “damn.”

Taking language back

The “Let’s go Brandon” phenomenon also illustrates the process of linguistic reappropriation or reclamation.

Some Biden supporters are turning the phrase into one of support for him. And as a variant, some of the president’s supporters have begun to employ, “Thank you Brandon.”

This is itself a callback to the earlier “Thanks, Obama.” Republicans often used the phrase to sarcastically criticize the 44th president, but it was later reappropriated by Democrats who used the phrase literally. The dizzying linguistic arms race eventually rendered the phrase meaningless.

As with minced oaths, there’s an equally long history of insults being adopted by the groups being disparaged.

During the English Civil Wars, for example, Parliament supporters mockingly referred to the backers of Charles I as “Cavaliers.” In a feat of verbal judo, the royalists adopted the moniker to refer to themselves. By doing so, they drained away the epithet’s negative connotation.

A similar process has occurred for the use of the word “queer.” Once a highly offensive slur directed at gay people, the LGBTQ+ community adopted and rehabilitated it.

Several other cases of linguistic appropriation have recently occurred in U.S. politics. A good example is “Nevertheless, she persisted.” Republican senator Mitch McConnell first used it to rebuke Democratic senator Elizabeth Warren, who read from a letter by Coretta Scott King during a confirmation hearing after McConnell had warned her not to.

Warren’s supporters quickly seized upon the slogan, proudly using it to celebrate women who resist being silenced. Chelsea Clinton went on to publish a series of books honoring women entitled “She Persisted.”

Republicans have proved just as adept at this as Democrats. In 2016, when presidential candidate Hillary Clinton said that half of Donald Trump’s supporters could be put in a “basket of deplorables,” the Trump campaign released commercials using it. Clinton’s words were played over clips of Trump’s admiring supporters.

A universal phenomenon

These phenomena aren’t limited to U.S. politics. Citizens in repressive societies employ coded criticism as a way to challenge authority.

Following the crackdown on dissent after the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989, demonstrators in China smashed glass bottles in public places to protest the policies of leader Deng Xiaoping. Although the connection is lost on those who don’t know Chinese, “Xiaoping” and “little bottle” are pronounced the same way in Mandarin.

NASCAR’s concern with its family-friendly image has caused its president, Steve Phelps, to distance the organization from the ongoing “Let’s Go Brandon” imbroglio. And a Southwest Airlines pilot is under investigation for using the phrase while airborne.

Others, however, have been happy to make use of the association. On Nov. 18, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, a Republican, made a point of signing bills outlawing COVID-19 vaccine mandates in an unincorporated community nearly 300 miles from the state capital.

Its name?

Roger J. Kreuz is an associate dean and professor of Psychology at University of Memphis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.