This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It was originally published at The Conversation.

In a case to be heard in the coming months, the U.S. Supreme Court could decide that state legislatures have control over congressional elections, including the ability to draw voting districts for partisan political advantage, unconstrained by state law or state constitutions.

At issue is a legal theory called the “independent state legislature doctrine,” which is posed through the court’s consideration of a dispute over gerrymandered North Carolina congressional districts. In early 2022, North Carolina state courts found the legislature violated the state constitution when it drew gerrymandered congressional districts favoring Republicans. The legislature has claimed that the U.S. Constitution gives it authority, unfettered by state courts’ interpretation of the state constitution or laws, to regulate congressional elections, and is asking the Supreme Court to agree.

If the court agrees, it could free state legislatures to take power away from voters – “We the People” in constitutional parlance – and reverse a two-century trend toward expanding the power of the people in congressional elections.

Some election and constitutional law analysts have already suggested that state legislatures may have similar power over presidential elections. The U.S. Constitution allows state legislatures to determine how a state chooses its presidential electors, arguably leaving the legislature free to choose presidential electors on their own without a popular election.

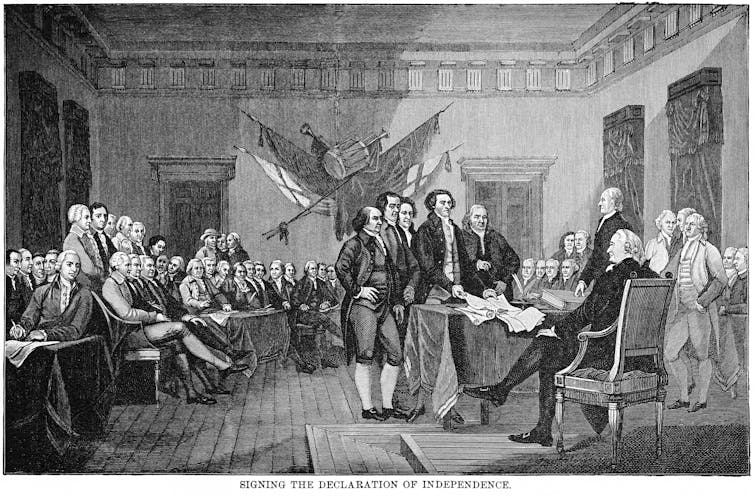

Power of the people in early America

The people wielded little power in congressional elections at America’s founding.

The unamended Constitution required United States senators be chosen directly by their state legislatures, not by voters directly. That was the case until the 17th Amendment was ratified in 1913, which requires U.S. senators to be elected by the people.

The Constitution has always required United States representatives be chosen by the people, but who could vote was severely limited.

America’s late-18th century vision of democracy treated voting as a privilege to be doled out by the state, not a right. Voting was typically limited to a narrow band of people – adult white men with property.

Some states, including North Carolina and New Jersey, allowed women or free Black men, or both, to vote in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Nonetheless, who could exercise power in congressional or state elections was a matter of grace provided by state legislatures.

Power of the people today

As U.S. democracy matured, the people gained power as the electorate expanded through various constitutional amendments.

Voting remains a right provided by each state. However, the states can no longer limit the right to vote based on race, sex, failure to pay a poll tax or age if a voter is 18 years or older. Functionally, adult citizens who have not been convicted of a crime have the right to vote in federal and state elections.

In addition, the value of a vote is protected. In the 1960s, the Supreme Court recognized the one-person, one-vote doctrine under the Constitution. That doctrine requires each congressional district in a state to contain approximately the same number of residents.

Before the doctrine was recognized, one congressional district in a state could have several times the population as another district in the same state. A vote in the larger district would have a fraction of the power of a vote in the smaller district.

In the wake of the one-person, one-vote doctrine, each vote carries approximately the same weight.

Undoing accountability

Providing voting power to the people makes representatives more accountable and answerable to their constituents. Adopting the independent state legislature doctrine may reverse the accountability.

Those who advocate the legitimacy of this doctrine say it rests on the Constitution’s grant to state legislatures of regulatory power over congressional elections in Article I, Section 4.

That section reads: “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations.” It gives state legislatures the primary authority to run congressional elections, subject to congressional regulation through federal law.

For example, for much of the nation’s history, states could choose U.S. representatives through districts or through an at-large system. However, federal law now requires the representatives to be chosen solely through districts.

In addition, state legislative power has been treated as though it is constrained by other state governmental actors. In many states, governors may veto redistricting maps they deem unfair or improper. Similarly, as in the North Carolina case, courts may deem such maps unlawful or unconstitutional.

A strong version of the doctrine might give a state legislature the power to draw congressional districts without any oversight from state courts or the governor. Given that state courts apply a state’s constitution and state statutory law, a strong independent state legislature doctrine could leave the state legislature unfettered by state law in this area.

However, in a well-functioning democracy, state constitutional and statutory law should reflect the preferences of a state’s people. The Supreme Court reminded the Arizona legislature of this point in a 2015 ruling that allowed a citizen initiative in that state to bypass the legislature in redistricting, instead requiring congressional districts to be drawn by an independent commission. If the independent state legislature doctrine were to be adopted by the current Supreme Court, that power could not be exercised by citizens.

Limited federal protection

If the court adopts the independent state legislature doctrine, legislatures would still be subject to regulation by the U.S. Constitution and by federal law, such as the Voting Rights Act.

However, the court has limited the protections embedded in the Voting Rights Act. In the 2019 ruling, Rucho v. Common Cause, the Supreme Court deemed partisan gerrymandering a political question, not subject to regulation by the Constitution. In that ruling, the court noted that state constitutional and statutory law could be used to stop partisan gerrymandering.

Three years later, the court is set to hear a case that could remove state courts from oversight of partisan gerrymandering by state legislatures. Adoption of a strong independent state legislature doctrine would leave partisan gerrymandering unregulated at both the state and federal levels.

State legislatures, unconstrained by state law, could then create aggressively gerrymandered congressional districts, possibly leading to an ever more partisan Congress with accompanying gridlock and policy failures.

Disempowering the people

When the Constitution was ratified, the state legislature was the locus of state power. That power was exercised by a few men who were not answerable to the broad populace. The state legislature was responsible for acting in the citizenry’s best interests. However, the citizenry had no effective way to force legislators to act in the people’s interests.

Over time, citizens have gained more control over state legislatures through an expanded vote and by becoming a larger part of the lawmaking apparatus of many states.

In a 21st-century democracy, the constitutional grant of regulatory authority to a state legislature regarding congressional elections might be thought to be a grant of primary authority to a state legislature – but an authority subject to a variety of other limits imposed via state constitutional law, state statutory law, the courts and the citizenry.

At America’s founding, the Constitution made the power of the people a matter of grace provided by state legislatures. As America’s democracy matured, the power of the people became a matter of right under the Constitution.

The independent state legislature doctrine threatens to make the power of the people a matter of grace again, reinstating an anachronistic vision of democracy long thought to have passed.

Henry L. Chambers Jr. is a professor of law at University of Richmond.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.