This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis.

“Immigrants are invading our country and replacing our cultural and ethnic background.”

According to a recent poll, 30% of Americans “completely” or “mostly” agree with this statement, often called the Great Replacement Theory. The poll shows that within that 30% are majorities of Republicans and of white evangelical Protestants, who believe that immigrants are entering the U.S. and “replacing our cultural and ethnic background.” According to cable news host Tucker Carlson, his listeners should fear “the replacement of legacy Americans with more obedient people from far away countries.”

One of the more dramatic ironies around replacement theory is that, at times in American history, political elites have actually sought to the replace the electorate. But it was not a case, as today’s conspiracy theory holds, that people of color were being brought in to replace white people — it was exactly the opposite. What Carlson claims is the goal of current U.S. policy — to “change the racial mix of the country” — was the fervent hope of the White South 150 years ago. Then, the defeated Confederacy also turned to immigration — as a deliberate tool to replace the electorate and maintain the imbalance of power.

During Reconstruction, Black and Brown people weren’t invading the country; to the contrary, they’d been forcibly migrated to America and enslaved. But by winning the right to vote, freed slaves had the potential not just to have a say in the governments of the White South but, in the words of W.E.B. DuBois, to “reconstruct democracy in America.” Plantation owners saw that revitalized democracy as a threat. To counter newly enfranchised Black voters, former slaveholders started actively encouraging the immigration of foreign-born whites, focusing on a “better class” of Germans and other Europeans.

After the Civil War, newly freed slaves outnumbered whites in many states across the South. “Legacy Americans” had exercised control before the war through lynchings, floggings and other means. In 1822, for instance, when freed slave Denmark Vesey was accused of masterminding a rebellion, the mayor of Charleston, South Carolina had called out the militia. Vesey and 35 others were hanged, 31 co-conspirators were deported, and the city’s security was boosted to where, years later, Lieutenant William Tecumseh Sherman would describe it as “policed to perfection.”

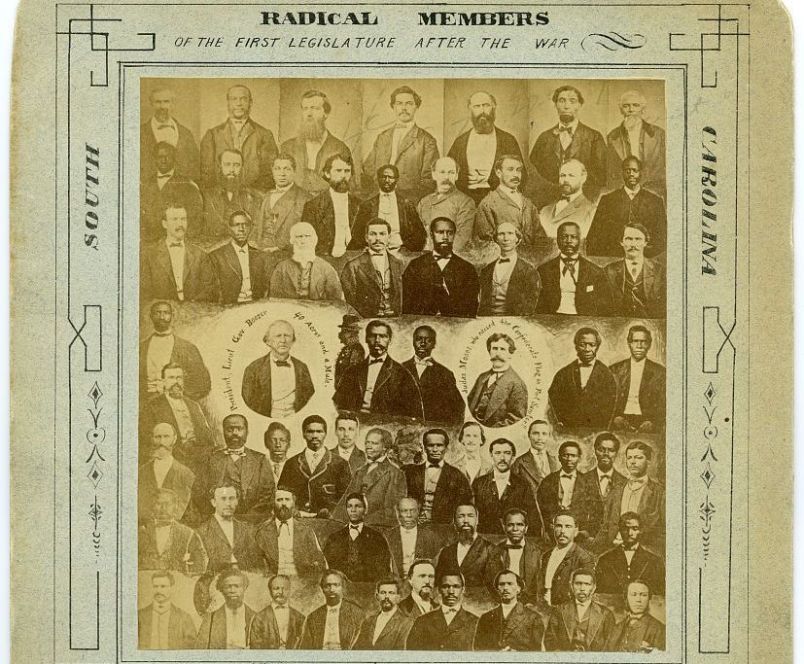

But the Civil War and the federal presence in the South after the war interrupted such “policing.” Meanwhile, newly freed slaves began to exercise their democratic rights. In the fall of 1868, 94% of South Carolina’s eligible Blacks registered to vote, a number that significantly outnumbered the state’s white electorate. (In 1870, South Carolina had 290,000 whites and 416,000 African Americans.) Nationally, 16 African Americans were soon elected to Congress and more than 600 to state legislatures. Many more won local office.

White southerners responded to this threat to their authority through legal and extralegal campaigns of terror, including an energized Ku Klux Klan. But they also devised a set of schemes to use immigrants — specifically, white immigrants — as a weapon.

Many states organized immigration commissions. South Carolina’s director of immigration, a former Confederate general, made the goal explicit. The state needed “men and women of our own blood and kindred.” In Alabama, a Mobile newspaper saw “the necessity of white immigration.” In Virginia, the Richmond Daily Dispatch believed “white immigration [would] give to the State a superior kind of industry and mechanical skill.” The ultimate goal, as South Carolina’s newspapers expressed it, was that “industrious, thrifty, enterprising white settlers” would, within a couple of decades, “throw the negroes into the shade.”

In 1866, the South Carolina legislature authorized $10,000 to encourage more foreigners to come to their state. That paid for the printing of 14,000 immigration pamphlets — in Danish, Swedish, German, and English — and for hiring agents to find likely candidates in northern Europe. North Carolina focused on British and Scottish farmers. Wilmington, Delaware would bring in Italian laborers to replace slaves. Along with Germans and Italians, Texas managed to attract a small number of Japanese rice farmers.

But all in all, the outreach didn’t work. According to the research of Professor Jeffery G. Strickland, South Carolina’s immigrant agents in Germany and Scandinavia failed to enlist a single family, and the state’s man in Ireland resigned and moved to Texas. On top of that, South Carolina’s merchants refused to support a steamship line to Europe. While former slaveholders were willing to welcome immigrants “as friends,” it turned out that many objected to treating them as equals. “Let us have not,” one declared, “social equality with our laborers.”

From their side, the immigrants felt unwelcome — or worse. Promotional material was often overtly racist, extolling the South’s former slavery system in an attempt to attract “ideal” immigrants with similar values. Instead, many immigrants ended up seeing white southerners as “lawless and semi-barbarous.” Some potential immigrants concluded that, despite the Confederacy’s defeat, its core values still held sway — and feared that “if they were to come to the South they would be made slaves instantly.”

The unwelcoming South and the foreigners’ suspicion of same meant that the efforts of South Carolina’s Immigration Bureau resulted in a total of only 147 new citizens. By the turn of the century, the entire South, including the old border states, had about as many foreign-born as Michigan; New York had three times as many. The combined immigrant population of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina barely equaled that of Vermont.

Today’s Great Replacement Theory is driven by the same fear plantation-owners felt in the Reconstruction South: that whites would be out-numbered by Black voters. Then as now, the goal of the white minority was to hold onto power. While the former Confederate states distracted the populace with talk of immigration, they simultaneously enacted new Jim Crow laws that successfully rolled back the gains of Reconstruction. That rollback remained for another century, until the modern civil rights movement. And what gains have been made since are once again in jeopardy. Then as now, immigration was a buzzword meant to heighten fear and maintain the status quo. Then as now, “foreigners” proved secondary compared to the far more effective program for keeping power in the hands of Whites: the suppression of voters’ rights.

Daniel Wolff’s most recent non-fiction book is “How To Become An American: A History of Immigration, Assimilation, and Loneliness” (University of South Carolina Press).