This piece is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It is an excerpt from “Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events,” out this month.

The wage-price spiral narrative took hold in the United States and many other countries around the middle of the twentieth century. It described a labor movement, led by strong labor unions, demanding higher wages for themselves, which management accommodates without losing profits by pushing up the prices of final goods sold to consumers. Labor then uses the higher prices to justify even higher wage demands, and the process repeats itself again and again, leading to out-of-control inflation. The blame for inflation thus falls on both labor and management, and some may blame the monetary authority, which tolerates the inflation. This narrative is associated with the term cost-push inflation, where cost refers to the cost of labor and inputs to production. It contrasts with a different popular narrative, demand-pull inflation, a theory that blames inflation on consumers who demand more goods than can be produced.

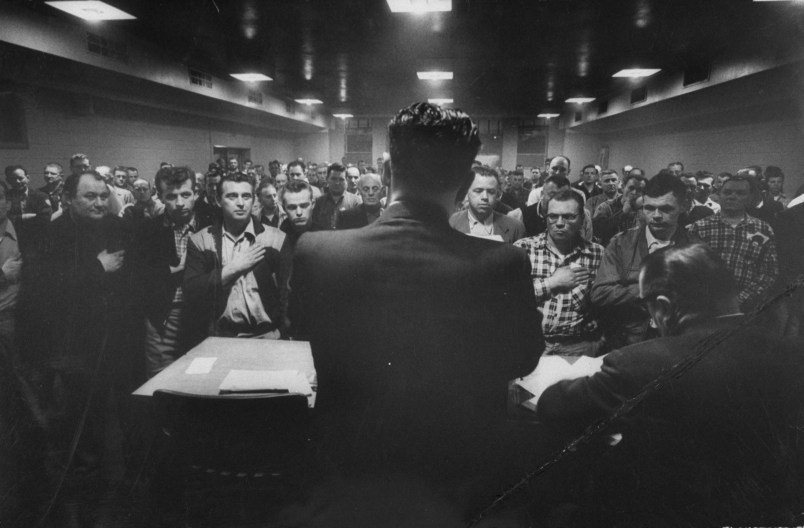

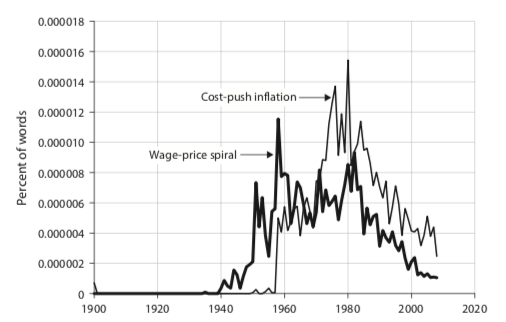

As the chart below shows, the two epidemics, wage-price spiral and cost-push inflation, are roughly parallel. Both epidemics were especially strong sometime between 1950 and 1990. These epidemics reflected changes in moral values, indicating deep concerns about being cheated and a sense of fundamental corruption in society. According to the narratives, labor unions were deceitfully claiming to represent labor as a whole, when in fact they were representing only certain insiders. Meanwhile, politicians and central banks were selfishly perpetuating the upward spiral of inflation, which impoverished real working people not represented by powerful unions. There has been a long downtrend in public support in the United States for labor unions, from 72% in 1936 to 48% in 2009, as documented by the Gallup Poll.

These narratives were enhanced by detailed stories that invited angry responses. For example, around 1950 an outrageous story went viral about labor unions’ reframing their wage in terms of miles traveled rather than hours worked. The New York Times described it thus in 1950:

One of the rule changes asked by these two unions is that the pay base for trainmen and conductors on passenger trains be lowered to 100 miles or five hours, from 150 miles or seven and a half hours. The railroads have countered by asking that the basic day’s work be increased to 200 miles. . . . Because of recent technological improvements, including the greater use of diesel locomotives, the speed of passenger trains has been increased, where many passenger train service employes now receive a day’s pay for two and a half to three hours of work. By reducing the number of miles in the basic day to 100, the mileage rate of pay of the passenger train employes would be increased by 50 per cent.

So, the story went, the conductors would have the opportunity to sit down as passengers after working only two and a half hours, long before the trip was over. Such an outrageous demand made the narrative highly contagious, and it is memorable enough to be remembered today.

Labor unions became associated in the public eye with organized crime. For example, Jimmy Hoffa took over the International Brotherhood of Teamsters union in 1957, despite corruption charges against him then, and led that union as an absolute dictator. There was for years an ongoing story of his investigation for gangster-like activities, in a probe led by Robert F. Kennedy. Hoffa was convicted of bribery and fraud and went to prison from 1967–71. In 1975 he disappeared after being last seen in the parking lot upon leaving the Red Fox Restaurant in Bloomfield Township. Rumors were that he was murdered by rival gangsters. Rumors were that his body “was entombed in concrete at Giants Stadium in New Jersey, ground up and thrown in a Florida swamp, or perished in a mob-owned fat-rendering plant.” These colorful theories, which suggest vivid visual mental images of Hoffa’s ignominious end, led to the contagion rate of the Hoffa epidemic that further discredited labor unions. The search for his body in a garbage dump, an empty field, and elsewhere created news stories until 2013. This was a viral story, part of a constellation of narratives that described labor unions in negative terms, and which impelled many people to see real evil in them.

The wage-price spiral narrative was reflected in actual inflation rates around the world, which tended to be unusually high when the narrative was strong. The World Bank’s Global Inflation Rate peaked in 1980, approximately at the peak of cost-push inflation in the chart above, and it has been mostly on the decline ever since. These epidemics also saw high long-term interest rates, reflecting the inflation expectations engendered by the narrative. Today, inflation is down across much of the world, and long-term interest rates have fallen since the epidemic peaked. The dynamics of this worldwide narrative epidemic likely provide the best explanation for these epochal changes in trend of the two major economic variables, inflation and interest rates.

The end of the wage-price spiral narrative was marked by changes in monetary policy and the advent of newly popular ideas: the independent central bank and inflation targeting by central banks. The independent central bank was designed to be free from political pressures, which organized labor tries to exploit. Inflation targeting was designed to place controlling inflation on a higher moral ground than appeasing political forces.

The moral imperative here was strong. On its face, the wage-price spiral may seem purely mechanical. However, many believed it was caused by the greedy (immoral) behavior of both management and labor. President Dwight Eisenhower referred to the spiral in his 1957 State of the Union address:

The national interest must take precedence over temporary advantages which may be secured by particular groups at the expense of all the people. . . . Business in its pricing policies should avoid unnecessary price increases especially at a time like the present when demand in so many areas presses hard on short supplies. A reasonable profit is essential to the new investments that provide more jobs in an expanding economy. But business leaders must, in the national interest, studiously avoid those price rises that are possible only because of vital or unusual needs of the whole nation. . . . Wage negotiations should also take cognizance of the right of the public generally to share in the benefits of improvements in technology.

Even though 1957 saw only a moderate burst of inflation, from less than zero in 1956 to a peak of 3.7% in 1957 and far smaller than the 23.6% in 1920, it stirred emotions because of the moralizing narrative that attended it. A 1957 editorial in the Los Angeles Times exemplifies the reaction:

What is wrong with our country? A creeping inflation is like a small crack in a dam or dike as it grows menacingly larger by the force of the seeping water. The crack in our national economy is being widened by greed—greed of some leaders of big business and labor as they continue to boost prices and wages, each blaming the other, and neither pausing to realize that the economy of our country is at the breaking point with a crash being inevitable if we do not level off now and hold prices and wages. It may even be too late.

The moralizing in these narratives, spoken by presidents and prime ministers and published and commented on by journalists, gave the U.S. Federal Reserve and other nations’ central banks the moral authority to step hard on the brakes, risking a recession. They did just that, tightening money gradually until the discount rate rose to a peak in October 1957. Allan Sproul, the recently retired president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, in 1957 lamented the difficult role of the Fed as the “economic policeman for the entire community.” He noted the blame the Fed gets for the expansion before a crackdown:

As it is, there are times when your Federal Reserve System finds itself in the position of having to validate, however reluctantly, public folly and private greed by supporting increased costs and prices.

Inflation in a Constellation of Injustice and Immorality Narratives

When inflation has been high, many commentators have regarded it as the most important problem facing the nation. Starting in 1935, the Gallup Poll has repeatedly asked its U.S. respondents, “What do you think is the most important problem facing this country [or this section of the country] today?” During the era of highest U.S. inflation, from 1973 to 1981, generally more than 50% of respondents responded by saying either “inflation” or “the high cost of living.” This perception appears to have been common across much of the world. Reflecting this view, economist Irving S. Friedman wrote in his 1973 book Inflation: A World-Wide Disaster that the increasing inflation was sending “panic signals throughout the world,” opining that the inflation crisis was as serious a problem as the Great Depression of the 1930s. Inflation was “eroding the fabric of modern societies” and “threatens all efforts to keep the international monetary system from fragmenting into hostile forces.”

The discourse seemed to want to fix blame on some segment of society, either labor or business, for the inflation. Popular syndicated columnist Sydney J. Harris wrote in 1975:

What is so frustrating about this kind of thing is the difficulty in pinning down the culprits, if any . . .

Either somebody is lying, or the whole economic process doesn’t make sense.

If labor is getting “too much,” why are most working families struggling to make ends meet?

If grocers are “profiteering,” why do they get glummer as prices go higher?

Where does the buck stop? Nobody knows. And so each segment blames another for the vicious spiral, and each justifies its own increases by pointing to its own rising cost of doing business.

the market no longer seems to control prices when they keep escalating despite reduced consumption.

Some strange new twisted law appears to be operating in place of the classical formula of the “free market.”

I am not versed enough in economics to understand what is going on; neither are most people.

In contrast to the 1920s, there were now multiple possible sources of evil behind inflation, not so focused on evil businesses of various kinds, but now also on evil labor.

In my 1997 study of public views of the inflation crisis in the United States, Germany, and Brazil, conducted after the worst of the inflation had subsided but during a period in which people remained concerned about inflation, I surveyed both the general public and, for comparison, university economists. My research uncovered differences in narratives across countries, across age groups, and, particularly, between economists and the general public.

For the most part, the economists did not think that inflation was such a big deal, unlike Irving Friedman, who was writing for the general public. Meanwhile, although U.S. consumers did not agree on the causes of the inflation, they were nonetheless angry about it. When asked to identify the cause of the inflation, their most common response was “greed,” followed by “people borrow or lend too much.” In specifying the targets of their anger, the U.S. respondents listed, in order of frequency, “the government,” “manufacturers,” “store owners,” “business in general,” “wholesalers,” “executives,” “U.S. Congress,” “greedy people,” “institutions,” “economists” “retailers” “distributors,” “middlemen, “conglomerates, “the President of the United States,” “the Democratic party,” “big money people,” “store employees” (for wage demands that forced price increases), their “employer” (for not raising their salary), and “themselves” (for being ignorant of matters).

In addition, unlike economists, the general public believed in a wage lag hypothesis: the idea that wage increases would forever lag behind price increases, and therefore that inflation had a direct and long-term negative impact on living standards. In short, the wage-price spiral offered a geometrical mental image of one’s economic status spiraling down for as long as strong aggressive demands of labor kept it happening.

In some ways the 1957–58 recession differed substantially from earlier recessions. It did not have the character of a buyers’ strike, as the Great Depression did. In fact, sales of luxury items remained very strong. Anger was not so much directed against “profiteers,” and there was little shame in living extravagantly. The alarmist talk about the wage-price spiral did not focus anger onto the rich. Rather, sales of postponable everyday purchases suffered more.

At the same time, the public sensed that no feasible government policy could stop the wage price-spiral. The earlier recessions of 1949, 1953, and 1957 had left inflation a little lower, but only temporarily. The lingering narrative of the Great Depression suggested to the general public that it was perhaps too great a risk to try to control inflation by starting a bigger recession. That idea was part of the popular conception of the wage-price spiral model, that the nation should base all of its economic decisions on the assumption that inflation will get worse and worse.

Angry at Inflation

Out-of-control consumer price inflation has occurred many times throughout history, and the phenomenon has always induced anger. The loss of purchasing power is extremely annoying. But the question is this: At whom should the public direct its anger? Anger narratives about inflation reflect the different circumstances of each inflationary period. By studying these narratives, we can see the effects of inflation and how they change through time.

The most extreme cases of inflation tend to happen during wars. When governments are in trouble, they may not be able to collect taxes fast enough to pay for the war, and in desperation they resort to the printing press for more money. But the stories may not resonate, and the public may not see or understand what is happening. That is, narratives that blame the government for the inflation may not be contagious during a war. Instead, it is more likely that people want to blame someone else. Businesspeople, who are staying home safely while others are fighting, are a natural target of narratives.

We saw the remarkable epidemic of the word profiteer during and just after World War I. People were very angry that some businesspeople were made rich by the war, and the result was the imposition of an excess profits tax (not only during World War I but also during World War II). Such anger against the people who get rich during wartime is a perennial narrative, not limited to the twentieth century. For example, there was anger during the U.S. Civil War (1861–65) at those who profited from the war, but it wasn’t directed at business tycoons creating inflation to make large profits. The narratives were different. Consider, for example, this sermon by Reverend George Richards of the First Congregational Church of Litchfield, Connecticut, on February 22, 1863:

How, in contrast with the greedy speculators, in office and out of it, who have prowled, like famished wolves, round our fields of carnage—stealing everything they could lay their hands on—robbing the national treasury—purloining from the camp-chest—pilfering from the wounded in the hospitals—appropriating to themselves the little comforts meant for the dying, if not stripping the very dead!

During the 1917–23 German hyperinflation, the inflation rate was astronomical, and not due to any war. Prices in marks rose on the order of a trillionfold. And yet many people were unable to identify the malefactor who was causing inflation. Irving Fisher, an American economist who visited Germany at the time, found that Germans did not blame their own government, which had been printing money excessively. Fisher wrote:

The Germans thought of commodities as rising and thought of the American gold dollar as rising. They thought we [the United States] had somehow cornered the gold of the world and were charging an outrageous price for it.

As of this writing, there is some suggestion of resurgence in the strength of labor unions, and of public support for them, in the United States. The wage-price spiral narrative does not seem poised to reappear. Inflation in the United States and other countries seems unusually tame. However, a mutation of the narrative could appear if inflation begins to creep up. The public tends to watch consumer prices closely, because of its constant repetition of purchases. The wage-price spiral narrative, or some variation on that theme, could again create a strong impulse for economic actors to try to get ahead of the inflation game. It could give them newfound zest in this effort by bringing a moral dimension into the mix, a perception of true evil in inflation, personified by certain celebrities or classes of people.

Robert J. Shiller is a Nobel Prize–winning economist, the author of the New York Times bestseller Irrational Exuberance, and the coauthor, with George A. Akerlof, of Phishing for Phools and Animal Spirits, among other books (all Princeton). He is Sterling Professor of Economics at Yale University and a regular contributor to the New York Times. He lives in New Haven, Connecticut. Twitter @RobertJShiller