Research has long shown that empathy stems from two different factors. One is emotional, meaning empathy is triggered by your baggage, your family experience, what you bring to the table. The other is cognitive, which is your perspective, and, say, how interested you might be in hearing another person’s side of the story. Empathy is also different than sympathy; the former is sharing someone’s feelings because you understand that feeling, explains Brene Brown, a research professor at the University of Houston, in this amazing video. Sympathy is about feeling sadness for someone’s problems, but it doesn’t connect you to that person.

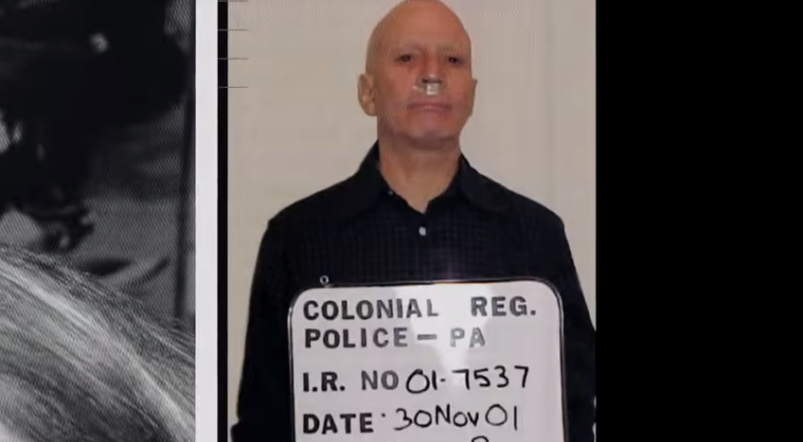

The topic of empathy and sympathy came to mind while watching the finale of HBO’s The Jinx, where murder suspect Robert Durst whispered his now-famous admission, “I killed them all.” I reached over and grabbed my husband’s elbow in horror when I heard it, but what I didn’t expect was to feel a wave of sorrow for him. I had so much pity (or sympathy) as well as empathy, for this awful, awful man, mic’d up and peeing in the bathroom, talking to himself, vulnerable and careless like a lonely, desperate child. It surprised me, this pity, despite being utterly creeped out; that night I dreamt there were heads in my attic, all hidden there by Durst.

What could possibly be wrong with me that I might have an ounce of empathy for Durst when clearly he had none for his victims? (Actually, scientists explain that serial killers, no matter what their background, have a chromosomal abnormality, which is why they feel no empathy for their victims.) I found my own thoughts so disturbing that I was grateful to see writer Sonia Saraiya tweet a similar thought: “By far the most interesting thing to me about “The Jinx” is how much, despite everything, I found myself feeling for the man.”

One study from 2010 suggests that avid literary fiction readers are more empathetic—that the “incompleteness of the characters turns your mind to trying to understand the minds of others,” wrote psychologist David Comer Kidd, one of the study’s authors. It’s possible that my English degree and my MFA in creative writing turned me into some kind of spineless empathy vessel.

When filmmaker Andrew Jarecki detailed Durst’s backstory—there was a pretty disturbing re-enactment of Durst’s mother jumping from a rooftop while a 10-year-old Durst watches from a window—he helped to create a multi-dimensional “character.” Anyone with a heart could feel bad for the man. Though his mother’s suicide is on record, Durst’s witnessing of it hasn’t fully checked out (his brother Douglas says it didn’t happen that way). But I can’t help but want to go back and hug young Durst. Stroke his face and tell him it’s okay. It’s where my empathy comes into play—maybe it’s something to do with my parent’s divorce (though my parents are still very much alive), or maybe it’s something to do with seeing him so exposed and depressed.

Yet, this isn’t a feeling I’m comfortable with. As much empathy I have for Durst as a child, I’m reminded of Durst’s victims. Kathie Durst’s brother’s interview hit me hardest. I have a brother. I’m close with him. I could see him being interviewed for a documentary, if for some reason I went missing; I could imagine the pain in his voice and it’s unbearable.

But most likely my response is because of Durst himself. Durst isn’t your typical Manson-like serial killer. He’s more like a nebbishy uncle, with his voice trailing in that upward tone. He’s an old Jewish guy snacking on pickles on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. “I did not murder my best friend.” Pause. “I did dismember him.” His face crumples up in what seems like self-loathing moment. We can attribute this to mirror neurons. When we interact, explains neuroscientist at the University of California at Los Angeles Marco Iacoboni, in an interview with Scientific American, “we use our body to communicate our intentions and our feelings. The gestures, facial expressions, body postures we make are social signals, ways of communicating with one another.”

That’s when mirror neurons get switched on and allow us to “mirror” emotions that we see in other people’s facial expressions. For example, I see you smiling and I smile back. With Durst, it’s possible that my mirror neurons got switched on because of his clearly uncomfortable and painful expressions—he couldn’t stop himself from burping in the last episode and I immediately thought, his agita acted up because he’s nervous, terrified. He covered his hands with his face, rubbing it the way my son does when he’s about to cry. My mirror neurons lit up like a neon sign. Distress! This man, as close to the devil incarnate as he might be, is in distress. It’s why I probably also felt empathetic for the Menendez brothers when they cried on the stand about killing their parents.

If any of you are screaming “hybristophilia”—also known as the Bonnie and Clyde syndrome in which women are sexually attracted to serial killers—that’s not what I’m talking about here. There’s no sexual attraction for Durst or Charles Manson or Ted Bundy. On the other hand, maybe hybristophila is what makes Jamie Dornan’s character in the BBC’s The Fall so attractive. Dornan’s character, Paul Spector, is a loving father. He cuddles with his daughter and son, reading to them under starry night lights and butterfly mobiles. Spector’s an abandoned orphan too. I’m turned on by him, yes. But not because he’s slowly strangling women. Because there’s a softer side to this human. He’s a human, after all—not a monster.

Hayley Krischer is a freelance writer based in New Jersey. Her work has appeared in The Toast, The Hairpin, Salon, The New York Times and other publications. You can find her on Twitter.