This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis.

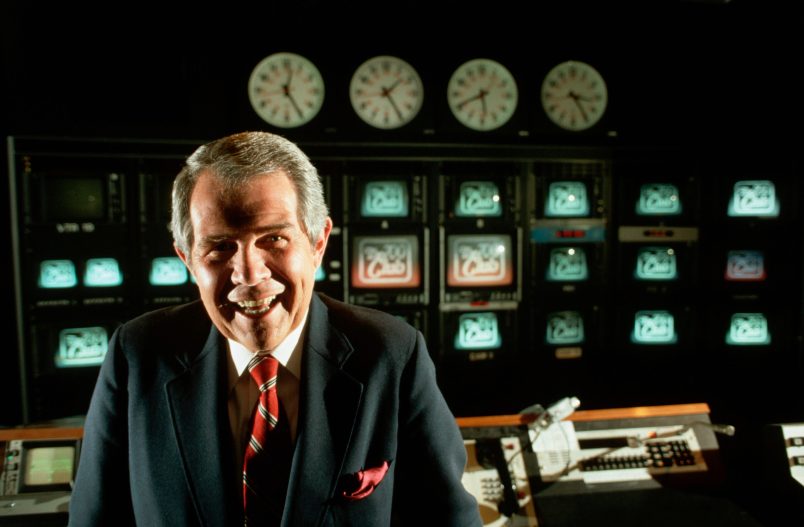

Christian Coalition and Christian Broadcasting Network founder Pat Robertson, who died Thursday at the age of 93, is best known for his failed foray into the 1988 GOP presidential primary, his training of evangelicals to be both successful candidates and reliable voters, and his decades-long highlight reel of homophobia, misogyny, racism, conspiracy theories, apocalyptic warnings, and pronouncements of God’s impending wrath on America for the sins of the left.

Less well understood, though, was Robertson’s significant contribution to the Christianization of the legal profession, and the development of a Christian nationalist legal brigade that has set its sights on ending the separation of church and state, abortion and LGBTQ rights. In 1986, he came to the rescue of a fledgling Christian law school, over the years turning it into the powerhouse Regent University School of Law that has produced lawyers who have gone on to become state court judges, appellate litigators, Republican lawmakers, and political appointees in Republican administrations.

The roots of Robertson’s law school can be traced to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where, in 1979, his friend and fellow televangelist Oral Roberts founded its original iteration at his eponymous university, with seed money from O.W. Coburn, a local entrepreneur and father of future Oklahoma Senator Tom Coburn (R). Also key to the development of a law school that would teach the law from a “biblical worldview” was Herb Titus, a Harvard-trained lawyer who became an acolyte of R.J. Rushdoony, the founder of Christian Reconstructionism, the radical movement at the core of Christian nationalist legal thinking that asserts that biblical law must govern every facet of public and private life. Rejecting secular law after reading Rushdoony’s seminal book, The Institutes of Biblical Law, Titus believed he had a “dominion mandate” to “restore the bible to legal education.” One of the law school’s first students was future GOP congresswoman and presidential candidate Michele Bachmann, who is now the dean of the Robertson School of Government at Regent.

The law school’s first conflict with the secular world portended the battles that have defined the religious right’s ongoing quest to expand religious freedom for conservative Christians and shrink it for everyone else. Because the law school required both students and faculty to sign a statement of Christian faith and profess belief in Jesus as their savior, the American Bar Association refused it accreditation, saying the requirement ran afoul of ABA’s prohibition against discrimination in the profession. The denial posed an existential threat to the school, since most states require graduates to have a degree from an accredited law school in order to sit for the bar exam. To Titus, who believed the ABA’s refusal to accredit the school was “pure religious prejudice,” Roberts was a hero because he refused to “bow down to the establishment.” The school sued the ABA, eventually forcing it to amend its standards to permit the type of faith statement ORU required, and paving the way to its accreditation.

Even with this victory, the law school struggled, something Titus chalked up to the idea of a Christian law school being ahead of its time, a country wracked by anti-Christian sentiment, and students unwilling to take a chance on this radical new kind of legal training. But Robertson, from over a thousand miles away in Virginia Beach, Virginia, was a believer. By 1985, when the school found itself with just eight faculty members and 129 students, Robertson rode in on a proverbial white horse.

The announcement of the transfer of the law school from ORU to Regent (then known as CBN University) was laden with language typical of both Robertson’s and Roberts’s charismatic, prosperity gospel faith. Roberts described it as a “seed-faith gift” to CBN, implying not only ORU’s generosity, but the prospect of God’s blessing and return on the investment. (Roberts taught God would bless the sower of a “seed” gift by meeting all their spiritual, material, and health needs.) Without much evidence, Robertson pronounced the gift worth $10 million, a dubious valuation given it had a smaller faculty than many preschools. Robertson, who two years later would launch his presidential run, called it “a historic moment in American Christianity” and “a testimony before America that those who work for Jesus are co-laborers.”

Nearly forty years later, Oral Roberts’ prediction that the law school would grow “stronger and stronger under Pat’s leadership” certainly proved true. It is the training ground for Christian lawyers who oppose LGBTQ rights in the name of religious freedom for anti-LGBTQ Christians, and who question the separation of church and state. “The faculty at Regent were on the front lines against marriage equality, and they are some of the leading voices opposing LGBTQ rights,” Josiah Robinson, a 2021 graduate who was closeted for most of his time there and is now a queer rights activist, told me last year. “They’re the law review scholars and the legal professionals on religious liberty used as a tool to discriminate.” One of its most acclaimed graduates is Kristen Waggoner, who, as counsel for Alliance Defending Freedom, the top Christian right litigation firm in the country, successfully argued Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission before the Supreme Court, notching a significant “religious freedom” victory for a baker who had refused to make a cake for a gay couple. Waggoner is now CEO and president of ADF, which, in recent months, has led the legal fight to reverse the FDA’s approval of the abortion pill mifepristone and to otherwise restrict access to safe abortion.

Regent has produced a lot of Christian lawyers, and also its fair share of scandals. Monica Goodling, a political appointee in George W. Bush’s Department of Justice, was at the center of a political scandal for leading an effort to query job applicants about their political beliefs in the quest to staff the agency with people with conservative Christian values. She was later reprimanded by the Virginia State Bar. Mark Martin, a former chief justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court, and then the dean of Regent School of Law, helped write a brief for former President Donald Trump in his failed legal effort to get the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn the 2020 election results in four states. Dan Cox, the far-right, election-denying Republican nominee for governor of Maryland last year, who had chartered three buses to the insurrection and tweeted (and later deleted) that Mike Pence was a traitor, is a 2006 graduate.

Robertson, in his prime, was one of the top architects of the religious right that was built in the 1970s and ‘80s. But it was perhaps his salvaging of someone else’s vision — a Christian law school to train Christian lawyers to litigate, enmesh themselves in politics, and even run for office — that could prove to be his most lasting, and damaging, legacy.