This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It was originally published at The Conversation.

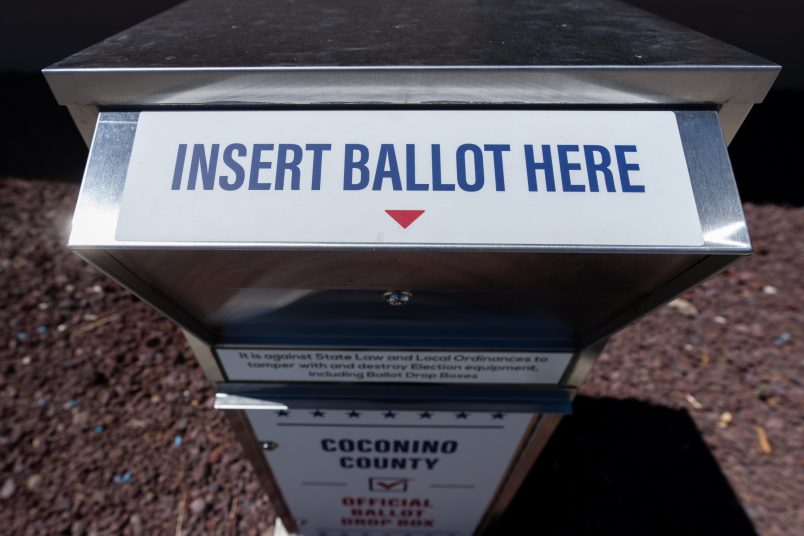

A couple in Mesa, Arizona, was dropping off their ballots on Oct. 21, 2022, for the forthcoming midterm election when they saw two people carrying guns and dressed in tactical gear hanging around the Maricopa County drop box. The armed pair left when officers later arrived.

It wasn’t an isolated incident. A lawsuit filed Oct. 24 by Arizona Alliance for Retired Americans and Voto Latino noted that on several occasions “armed and masked individuals” associated with the group Clean Elections USA had gathered at drop boxes in the county “with the express purpose of deterring voters.”

Voter intimidation is a crime in Arizona – as it is throughout the country. In the case of Maricopa County, a judge ruled on Nov. 1 that the actions of the individuals – who present themselves as anti-voter fraud activists – crossed the line and issued a restraining order. Under the order, people associated with Clean Elections USA are now barred from openly carrying firearms within 250 feet of a ballot box. Concealed firearms will be permitted, though, and the restriction only affects individuals connected to Clean Elections USA.

The presence of armed individuals at voting sites adds to concerns over the prospects of election-related intimidation and violence, which have deepened in recent years.

As Rachel Kleinfeld, senior fellow in the Democracy, Conflict, and Governance Program at the nonpartisan Carnegie Endowment, recently reported to the congressional committee looking into the Jan 6. attack on the Capitol, political violence “is considered more acceptable” by the public than it was five years ago.

False charges of stolen elections – such as those repeatedly made by former President Donald Trump – are “a major instigator of political unrest,” Kleinfeld noted, although she added that extremists in both political parties have reported a greater willingness to resort to political violence.

These concerns are far from hypothetical: As of this fall, more than 1,000 threats to election officials – some explicitly mentioning gun violence – were under review by federal law enforcement agencies. Responding to the situation in Arizona, the Department of Justice on Oct. 31 noted that the presence of armed individuals raises “serious concerns” of voter intimidation.

Such concerns are fanned by the fact that only seven states ban all gun-carrying at polling places. Five more states bar the carrying of concealed guns at polling places. But in swing states like Florida, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, people are allowed to carry guns even while they are voting.

The lack of a federal ban on firearms at voting sites has prompted Senator Chris Murphy, D-Conn., to introduce in Congress the Vote Without Fear Act, proposed legislation that would “prohibit the possession of a firearm within 100 yards of any federal election site.”

Pitched battles, and voter intimidation

To be sure, election-related violence is a part of America’s past. For example, the anti-immigrant Know-Nothing party of the 1850s often employed armed violence using an array of weapons, and Democrat-Whig party battles erupted in the 1830s. Throughout the middle of the 19th century, such cities as Philadelphia, Baltimore and New Orleans at times witnessed pitched battles between warring political factions at election time. And lethal violence was used extensively after the Civil War to systematically terrorize and disenfranchise Black voters in the South.

Yet many people in the United States also believed from the start that guns and violence were contrary to the values of a democratic nation, especially, though not limited to, during times of elections. As early as 1776, Delaware’s state Constitution stated: “To prevent any violence or force being used at the said elections, no person shall come armed to any of them.” It further stipulated that, to protect voters, a gun-free zone would be put in place within a mile of polling places for 24 hours before and after election day.

In its state Bill of Rights of 1787, New York decreed that “all elections shall be free and that no person by force of arms nor by malice or menacing or otherwise presume to disturb or hinder any citizen of this State to make free election.”

In my own research on historical gun laws, I found roughly a dozen states that specifically barred guns during elections or at polling places in laws enacted between the 1770s and the start of the 20th century. But even more importantly, from the 1600s through the 1800s, I found that at least three-quarters of all Colonies and later states enacted laws criminalizing gun-brandishing and display in any public setting – and that would certainly include voting stations at election time.

As I discuss in my new book, “The Gun Dilemma,” early American lawmakers well understood that public gun-carrying, by its very nature, was intimidating. And that extended not only to brandishing a gun, meaning displaying one in a threatening manner, but also to mere gun display – simply showing a gun in a public setting.

Modern studies confirm this understanding. Analysts in fields including psychology and criminology have concluded that the mere presence of guns increases aggression and violence. To cite a different analysis, a study of over 30,000 demonstrations in the U.S. from 2020 to 2021 found that when guns were present, protests were over six times more likely to turn violent or destructive.

Creating an ‘island of calm’

According to polls, wide majorities of Americans oppose public gun-carrying. A 2017 study reported that from two-thirds to over four-fifths of respondents opposed public gun-carrying in various settings, including at the polls. And as recently as 2018, the Supreme Court affirmed that Election Day polling places should be “an island of calm in which voters can peacefully contemplate their choices.”

Both history and modern research support the conclusion that the presence of guns in public defeats this goal. Indeed, they can induce “great fear and quarrels,” or so said New Jersey in a law passed in 1686.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.