This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It is an excerpt from “UNRIGGED: How Americans Are Battling Back to Save Democracy”, by David Daley, out today.

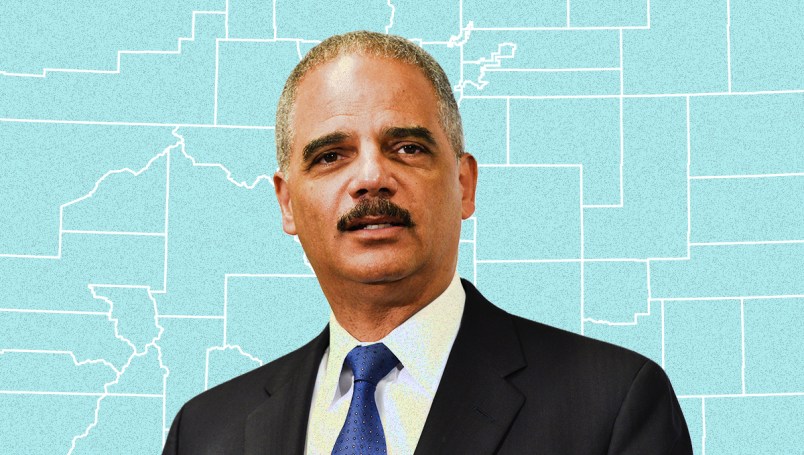

When Eric Holder vowed to make redistricting sexy, he probably didn’t see this evening coming. It’s a Monday evening in late July 2018, and Holder has been pinned in a Columbus, Ohio, kitchen by a wealthy workers’ comp attorney with an unearthly pinkish-tan glow. The local lawyer, a big Democratic donor, stands between the former attorney general and an actual gazpacho fountain. The attorney wears a partially unbuttoned blue gingham shirt and alligator loafers with no socks. He gestures with a giant glass of rosé, some of which spills onto Holder’s non-alligator shoes, while he emphatically explains why he’s finished donating to Ohio congressional candidates. His money will be given strategically, instead, to two otherwise anonymous down-ballot races, because the winners will hold a seat on Ohio’s redistricting commission.

“I’ll write a big check!” he tells Holder. “You know I’ll write a big check!” he adds enthusiastically, pointing his glass toward his candidate of choice, Zach Space, the Democratic auditor nominee. “You wrote me a big check today!” Space says quickly and appreciatively, wearing the pinned-on permasmile of any politician at a party with their awkward new benefactor. But the congressional folks? Cut off! The lawyer told the party so today. “They called me and I said, ‘I’m not giving you another dime.’ It’s gerrymandering! They get nothing ever again! I’m giving to the auditor and the secretary of state.”

In Ohio, even the lawyers who look freshly delivered from the Yellow Pages’ back cover are woke. Gerrymandering has turned this bellwether state’s politics inside out, securing Republicans a 12–4 edge in Congress and supermajorities in both state legislative chambers. Exactly 7 of the 297 races for the lower house between 2014 and 2018 have been within 5 points; heroes and legends like LeBron James or Ohio State football coach Urban Meyer can bring championships back home, but even Ohio’s most beloved figures would struggle to make those other 98 percent of the state’s house districts even remotely competitive.

That’s what brought Holder to this well-appointed home in his role as chairman of the National Democratic Redistricting Committee. He needs more donors and Democrats to connect the party’s ailing fortunes in states like this to the outrageously tilted districts Republicans drew during the last mapmaking process. There are still plenty of Democrats in Ohio; they’ve simply been cracked, packed and stacked so they can’t win many elections, ratfucked into oblivion by brilliant mapmakers and strategists who, unlike 2010’s Democrats, understood that winning the contests for auditor and secretary of state brought the power to banish the other side to political Antarctica.

“This is about fairness. They’re a minority power exercising supermajority power. That has to stop,” Holder tells the assembled crowd. The living room is rapt and alive; the fancy hors d’oeuvres are wrapped in bacon; every book on display has something to do with the musical Hamilton. “If we have a fair fight, we will do just fine. But you have to forget this notion of down-ballot. And you can’t just yell at the TV, at MSNBC or Colbert.”

“We shoot the TV in Ohio,” interrupts the lawyer from the kitchen.

Such was Eric Holder’s 2018. The former attorney general could have cashed in countless billable hours. He could have made bank on his status as the first African American to hold the office, or his long friendship with Barack Obama. Instead, he spent the year in living rooms like this, across our most gerrymandered states, urging Democrats to refocus on state legislatures and redistricting, pushing voting rights and a democracy agenda into the headlines and trying to make the least sexy contests just a little hotter. Over many months, I followed Holder into black churches and universities, house parties, law offices, even YWCA conference rooms as he rallied support for judges in North Carolina and Wisconsin, these easily ignored races in Ohio, and even called rural Georgians on behalf of Stacey Abrams and other local candidates from a nowheresville strip mall party headquarters next to the Licken’ Chicken’.

All of it was unglamorous. Much of it was thankless. In late 2017, both Holder and I were asked to discuss redistricting for a private audience of Democratic U.S. senators. Senators shuffled in and out of the ornate caucus room off the chamber floor. It was early, the morning after election day, but Democrats were ebullient from big wins in Virginia. The general elation made it all the more shocking when Senate Minority Leader Charles Schumer peered down at Holder, glasses on the tip of his nose, and pinned the party’s gerrymandering problem on race. The problem, Schumer fumed behind closed doors, was that civil rights groups and African American incumbents wouldn’t surrender even a piece of their safe districts for the general good of the party. What, he demanded to know, with a condescending tone that made me shiver and a racial undercurrent that made much of the room cringe, was Holder doing about that? Was he having conversations with those groups?

The kernel of truth inside Schumer’s otherwise off-base observation was decades old. During the 1990s’ redistricting cycle, Republicans and black Democrats joined forces as unusual, but understandable, bedfellows. Conservative white Democrats held a hammerlock on Southern politics; both Republicans and African Americans were underrepresented as a result. Blacks in North Carolina may have been reliable Democratic voters, but the state hadn’t sent a person of color to Congress since 1900. By 1994, North Carolina had two African American representatives, from districts packed with black voters. That year, however, Republicans took Congress for the first time in five decades. The packed “majority-minority” seats also bleached the surrounding districts whiter and more conservative, tilting them red.

The black caucus understood the devil’s bargain of cracking and packing and wished to be part of a Democratic majority, but they also harbored a natural distrust of white Democrats diluting their voice. Schumer’s racially-tinged outburst, however, was so disrespectful and condescending that I thought for sure the tension would escalate. But Holder quietly assured Schumer that he was in regular touch with civil rights groups. That’s when Missouri senator Claire McCaskill jumped in with her awkward race-related plaint. Missouri’s black members of Congress had such safe districts, she charged, that too many African Americans didn’t bother to turn out to vote for white statewide candidates, like, for example, herself. Could Holder make that clear in his meetings as well? The former attorney general had grown accustomed to this treatment in brutal oversight hearings from House Republicans; he likely didn’t expect it from his own side.

Holder, however, had quickly grasped how GOP gerrymandering caromed Democrats into the abyss, even if Schumer and McCaskill misunderstood the finer points. Not long after Barack Obama’s reelection in 2012, Holder told me, he and the president were looking over the numbers. “We thought we had done well in terms of the raw vote, but it wasn’t at all reflected in the number of representatives we had at both the state and federal level,” Holder says.

It’s the day after the Columbus house party and we’re in the parlor of a Cincinnati law office where he’ll soon hold a lunchtime Q and A with young Democrats, and Holder is recalling the confusion he and Obama discussed in the White House that day. “So what’s going on? REDMAP had been a small part of my consciousness before the 2012 election. I’d heard the phrase, but it wasn’t anything I had really focused on. Then we saw the election results.”

Democratic congressional candidates won 1.4 million more votes nationwide; Republicans held the House 234–201, thanks to a 56–24 edge from purple Pennsylvania (13–5), Ohio (12–4), Michigan (9–5), North Carolina (9–4), Virginia (8–3) and Wisconsin (5–3). If those fifty-fifty states had fifty-fifty delegations, the GOP edge would have been 218–217. It’s easy to imagine a very different second Obama term, with a smaller and less influential Freedom Caucus, much more incentive for compromise, and without government shutdowns or four dozen votes to repeal Obamacare.

Holder looks back on that election and realizes that Obama’s legislative agenda curdled the very night he won reelection. “There’s no question gerrymandering had an impact. I think it certainly shut down, in a substantial way, legislative avenues—which forced him to use executive power,” Holder reflects. “He had an impactful second term, but he did not have the ability to make it a durable one. The use of executive power, as we’ve now seen, can be reversed relatively quickly.”

Eric Holder became the nation’s top lawyer fewer than three years after the Voting Rights Act glided through reauthorization for another twenty-five years, backed by a Republican president, George W. Bush, and supported overwhelmingly by both houses of Congress, including a unanimous U.S. Senate. When President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law in July 1965, he proclaimed that “the right to vote is the basic right, without which all others are meaningless.” Forty-four years later, the job of enforcing this landmark legislation fell to the Holder, the nation’s first African American attorney general, just a teenager at the time but already on a path for law school.

In 2006, there was broad, bipartisan support for Section 5 “preclearance,” the Voting Rights Act’s most critical enforcement tool. It essentially placed on probation parts, or all, of sixteen states with a history of deeply rooted discrimination. If those entities wanted to alter their electoral laws, they had to prove there would not be any discriminatory purpose or effect. It was about to become much more controversial.

Not long after Republicans swept a record number of state legislative chambers in 2010, more than two dozen new state laws and executive orders targeted early voting, voter registration efforts and additional photo ID requirements. And when Holder’s Justice Department halted these voter suppression techniques under preclearance, citing discriminatory effects, a flurry of lawsuits resulted. It wasn’t 1965 any longer, not even in Alabama or Texas, these suits charged; they asserted that, in theory at least, a new era of equality existed, and defended the rights of these entities to make their own election laws. The federal government no longer needed to monitor every move. In the forty-five years between 1965 and 2010, there were only eight challenges to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act. Between 2010 and 2012 alone, there were nine.

Holder vigorously explained the theory behind Section 5 and defended its necessity. In a dramatic speech at the LBJ Library in Texas in late 2011, he stated his fear that some might “allow this time—our time—to be recorded in history as the age when the long-held belief that, in this country, every citizen has the chance—and the right—to help shape their government became a relic of our past.” His efforts, Holder said, honored the generations that took extraordinary risks, willingly confronted hatred and ignorance, and stood before billy clubs, fire hoses and bullets to fight for the right to vote as the very lifeblood of democracy.

Imagine, then, his profound dismay when the Supreme Court, in a 2013 case from Alabama called Shelby County v. Holder — “We only call it Shelby County,” Holder cracks when we discuss the case, with a wincing half-smile — overturned Section 5 as “based on 40-year-old facts having no logical relationship to the present day,” according to Chief Justice Roberts, in a nation that “has changed.” Holder had clerked with the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund as a law student and joined the Justice Department’s public integrity division straight out of Columbia, working on voting rights issues. Now the Court had gutted a key enforcement mechanism that protected democracy, and did so in a case bearing Holder’s name. “People had underestimated the importance of gerrymandering, the hollowing out of the Voting Rights Act,” Holder says. “You had conceptually the notion that this was not a good thing. But then it became real.

The Shelby County decision unleashed a wave of new voter suppression techniques blessed by a majority of Supreme Court justices. Texas implemented its strict photo ID law fewer than twenty-four hours after the court’s ruling. Alabama and Mississippi jumped at the opportunity to enforce voter ID laws that the Justice Department had previously blocked. Gerrymandered North Carolina, meanwhile, quickly went to work on H.B.589, a package of voting restrictions that included a voter ID bill that carefully targeted African Americans, in addition to ending same-day registration, annual registration drives and most early voting.

“These are civil rights issues,” Holder tells me. It’s just spreadsheets and data files instead of fire hoses and attack dogs. “We’re not fighting George Wallace and Bull Connor. But there’s a straight line between the civil rights movement and what we’re fighting now.”

Holder’s a Democrat. But he insists that the NDRC is not “a partisan attempt at good government.” The only way to “break this fever” of extremism in Washington and state capitals, he suggests, is by ensuring that neither party holds unilateral power over electoral maps. Neither Congress nor the Supreme Court seems likely to set fairness guidelines. Therefore, “you’ve got to elect Democrats, so that when the process happens again in 2021, you’ve got two parties at the table.” Now, that’s some nifty political jujitsu that might encourage, say, Republicans in Maryland, which is gerrymandered by the Democrats, to check for their wallet. Holder, however, pledges that he’ll fight any effort by Democrats to gerrymander where his party has complete control. “If that was the game, I wouldn’t put my name on it,” he insists. “Barack wouldn’t have put his name on it. It’s going to be on us to be critical of Democrats who do that, and, frankly, stop it from happening.”

In December 2018, Holder proved true to his word. New Jersey Democrats attempted to assure themselves unfettered power over the state’s bipartisan redistricting commission, reworking the state constitution to give legislative leaders the right to select its members. Holder blasted this as unfair and a step backward, which added to pressure on the legislature to back down.

It’s easy to be cynical about a partisan effort that promises it will reform partisan behavior. Believe him or not, however, Holder has been remarkably consistent: he wants to undo REDMAP, not install BLUEMAP. He’s convinced that Republican voters hate gerrymandering just as much as Democrats and independents do. Just look at Ohio, he says, where redistricting reform passed with more than 70 percent approval. Or Florida, where two Fair Districts amendments soared past 60 percent approval during the 2010 Tea Party wave. “Republicans, conservatives, independents, Democrats. The people get it,” he says.

And it’s the people who will have to fix it. Back in Columbus, Holder beseeches the room to become engaged citizens. “We have the capacity to create the change that we want,” he says, highlighting the civil rights movement, women’s rights and opposition to the Vietnam War as times when regular people “pushed, pushed, pushed” for change. “That’s what we have to do again.”

Excerpted from “UNRIGGED: How Americans Are Battling Back to Save Democracy” by David Daley. Published by Liveright, a division of W.W. Norton. Copyright 2020 David Daley, all rights reserved. Reprinted with permission of the author and publisher.

David Daley is the author of Ratf**ked. His journalism has appeared in the New Yorker, the Atlantic, Slate, the Washington Post, and New York magazine. He is a senior fellow at FairVote, the former editor of Salon, and lives in Massachusetts.