This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced democracy reformers to play defense, focusing their energy on the critical task of expanding vote-by-mail options and creating safe in-person polling locations. Most efforts to pursue non-emergency voting improvements have been put on hold.

In two states, though, advocates have a real opportunity to advance democracy in a bold way.

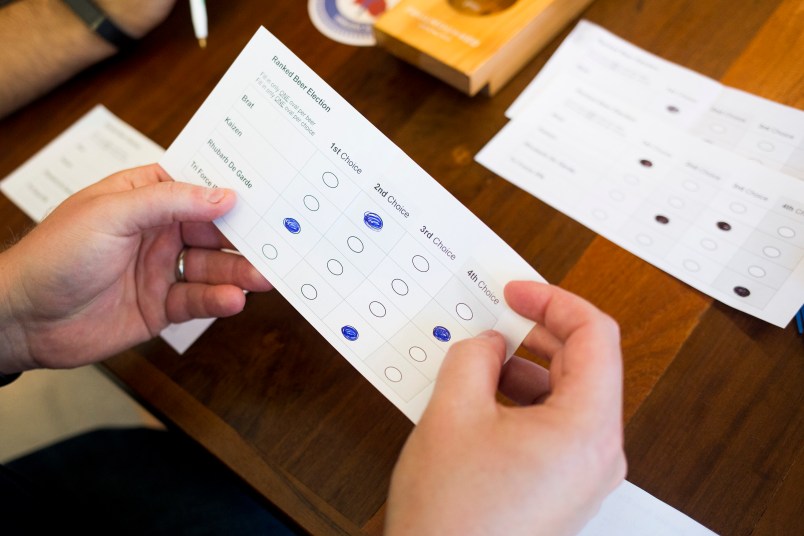

Ranked choice voting (RCV) will likely appear on the 2020 ballot in both Massachusetts and Alaska. This transformative reform, successfully implemented in Maine in 2018 and hopefully expanding further this year, would allow voters to rank candidates for state and federal office in order of preference. When the results are tallied, if no candidate receives more than 50% of the first place votes, then the last place vote-getter is eliminated and his or her votes are reallocated according to second choices. This process continues until one candidate has earned over 50 percent support. (Massachusetts’ measure would not apply to the presidential race).

The movement for RCV in Massachusetts has been years in the making. Since 2016, organizers have traveled across the commonwealth. They have held hundreds of informational sessions, trained countless volunteers, and secured bipartisan support from some of the state’s political leaders, including Sen. Ed Markey (D), Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D), Rep. Joe Kennedy (D), former governors Deval Patrick (D) and Bill Weld (R), and Secretary of the Commonwealth William Galvin (D).

Last fall, the RCV movement in the Bay State hit a remarkable milestone. After announcing intentions to bring RCV for primary and general elections to the ballot, advocates collected over 111,000 certified signatures to start the initiative process. Never before had so many certified signatures for a ballot measure been submitted in Massachusetts.

Under Massachusetts law, campaigners were required to collect a second round of 13,374 additional signatures to finalize their place on the ballot. But the timing could hardly have been worse: the period to gather more signatures coincided with the shutdowns due to COVID-19, which made it impossible for volunteers to collect additional in-person signatures at markets, festivals, street corners and so many other community events where people congregate. The campaign office closed and some declared the campaign dead.

But the leaders of Voter Choice for Massachusetts did not give up. They brought their case to the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, and won the right to collect signatures electronically. After weeks of intensive digital organizing, the group announced the submission of over 25,000 new signatures, having collected an average of one signature every two minutes for 40 days in a row. According to the campaign, this was the country’s first signature gathering drive for a ballot initiative conducted exclusively online. Assuming a majority of these signatures are certified, RCV will officially be on the 2020 Massachusetts ballot.

In Alaska, meanwhile, the effort to let voters choose RCV was bogged down in the state’s court system. Reformers there proposed a measure to implement a non-partisan top-four primary system, ranked choice voting in the general election and improvements to campaign finance transparency. At issue in the court challenge was whether this proposed measure violated the state’s rule for initiatives — requiring that they pertain to a “single subject.”

Last month, the Alaska Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the initiative did not violate the state’s Constitution. Advocates had already collected enough signatures to officially qualify for the ballot, so the measure is on track to go in front of voters on November 3.

In Alaska, there is some skepticism about the reform of the primary system.

“The ‘top-four primary’ presents potential drawbacks, especially if viable third parties or independents emerge and compete with multiple candidates from the major parties for only four spots in the general election,” Daily Kos Elections’ Stephen Wolf tells TPM. “Nevertheless, ‘top-four’ is much less likely to see the failures that ‘top-two’ primaries have caused in California and Washington where one of the two major parties gets shut out from a winnable general election solely because they had too many candidates splitting the primary vote.”

But RCV in both states is the big prize. The most well-known benefit of RCV is ensuring that the winner of an election receives support from the majority of voters. This is critical in heavily contested elections such as the 2018 Democratic primary for Massachusetts’ third congressional district. Ten candidates ran for the open seat and the ultimate winner, Lori Trahan, received a mere 21.7 percent of the vote. Four other candidates garnered at least 15 percent.

The current election system — in which almost 80 percent of voters can choose someone other than the eventual winner — does not ensure that our legislators have a broad base of support. (Trahan, to her credit, supports RCV.)

RCV also ends the debate over “spoiler” candidates, like previous third-party presidential candidates Ralph Nader, Ross Perot, and Jill Stein. With RCV, voters can cast a ballot for their preferred candidate, regardless of how “viable” they are. Supporting a lower tier candidate cannot affect the final outcome, because if the voter’s first choice performs poorly, the vote isn’t wasted. Instead, it’s redistributed to the voter’s next favorite candidate.

Alaskan voters are acutely aware of the spoiler effect. In 2018, the state held a competitive three-way election for governor. Incumbent independent Gov. Bill Walker faced off against Republican Mike Dunleavy and Democrat and former U.S. Sen. Mark Begich. Frustration mounted as Walker and Begich split the center-left vote in the polls, leaving Dunleavy — a far-right candidate — in the lead. With less than a month before Election Day, Walker dropped out of the race in an attempt to coalesce support around Begich, but in the end, Dunleavy won anyway.

“Restoring majority rule is critical in a state where elections have produced a winner with a mere plurality in more than half of the contests for governor since statehood and in the last five U.S. Senate races,” Wolf tells TPM. “Passing this proposal would thus be a positive step for Alaska’s democracy, and having different states adopt novel reforms provides us insight as to what works better and what does not.”

There are many other positive effects of RCV, including greater voter satisfaction. Evidence additionally suggests that RCV decreases negative campaigning, as candidates do not want to alienate their opponents’ supporters because second preferences matter.

Encouragingly, national support for RCV has grown in recent years. A handful of 2020 presidential candidates even endorsed the policy, most notably Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Michael Bennet (D-CO), and entrepreneur Andrew Yang.

Getting RCV on the ballot in Massachusetts and Alaska is a major victory for the democracy reform movement. Now begins the hard work of ensuring these initiatives are adopted. Running these campaigns during a pandemic presents challenges. Digital organizing, after all, is no substitute for door knocking and educating at mass gatherings.

2020 should have been a banner year for democracy reform. In 2016 and 2018, advocates across the U.S. put reform proposals on the ballot and won with widespread support. If not for COVID-19, this year would have built on that momentum. Advocates had planned major voting rights expansions and anti-gerrymandering initiatives, but they were largely derailed by signature gathering requirements made impossible by social distancing. That RCV organizers have put themselves in a position to win innovative reform in the current climate is remarkable. We cannot squander the opportunity that they have provided us.

Adam Eichen is the Campaigns Manager for Equal Citizens and co-author of Daring Democracy: Igniting Power, Meaning, and Connection for the America We Want.