This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. It was first published at The Conversation.

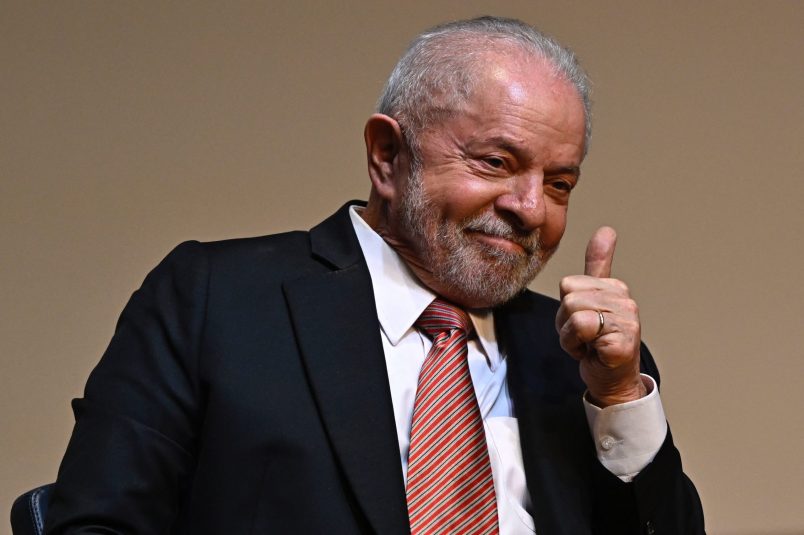

When Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva meets with President Joe Biden on Feb. 10, 2023, climate change, economic development and security will be on the agenda. But if Lula cannot stabilize his country’s democracy, he won’t be able to tackle any of these other goals.

Biden and Lula lead vastly different countries. Yet, the violent challenges each faced to their elections have given them similar battles to fight.

The Jan. 8, 2023, attack on Brazil’s capital echoed elements of the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. In both countries, incumbents who lost reelection began encouraging the violence weeks before their followers acted.

As an anthropologist who studies Brazilian politics, I see connections between how both riots were organized and the collective rage they conveyed. And I see the countries taking similar steps to shore up their democracies. The U.S. is two years into the process. But Brazil, where the insurrection was further complicated by military complicity, is just beginning the undertaking.

They acted on a lie

In both cases, rioters were convinced the election had been stolen from them and the candidates they backed – former President Donald Trump in the U.S. and Brazil’s former president, Jair Bolsonaro – despite there being no evidence of election fraud. In both cases, rioters organized online, and far-right influencers like Steve Bannon, who has had close ties to Bolsonaro since 2018, fanned the flames.

The rioters attacked physical symbols of democracy, like the Capitol in the U.S. and the National Congress and the Supreme Federal Court buildings in Brazil. In the U.S., rioters even openly called for the hanging and killing of elected officials. In Brazil, a nation once governed by a brutal military dictatorship, rioters pushed for a military takeover of the government.

The fact that so many people were moved from visceral anger to violence shows how easily people can be seduced by extreme ideology. That is a threat to democracy.

My book “Precarious Democracy,” which I co-edited with fellow anthropologists Lucia Cantero, Benjamin Junge and Sean Mitchell, demonstrates that political affect — the nonrational, emotional aspects of politics — can shape events in modern democracies.

Bolsonaro, for example, relied on portraying LGBT minorities as morally disgusting and a threat to the nation to rally support. That characterization was central to his electoral victory in 2018. Similarly, Trump — as candidate and president — cast immigrants as a threat to the United States. While Trump had an uncommon approach to the modern American presidency, his followers reveled in his norm breaking. And Bolsonaro validated conservatives’ emotional shift from hope to hate with the stoking of racial division and other tactics. As the anthropologist Patricia de Santana Pinho argues, Bolsonaro fomented a growing racial resentment among white Brazilians accustomed to being at the top of the country’s racial hierarchy, but who felt they had lost that privilege under Lula’s Workers’ Party. Bolsonaro promised to return to a mythical past when “there was decency and respect for the family,” using violence if necessary to achieve that goal. He even encouraged gun ownership as a way to reestablish social and moral order.

The challenges ahead

It is very hard to combat rage, resentment and nostalgia with appeals to rationality and civility. And Lula’s charge is further complicated by Bolsonaro supporters’ call for the return of military rule.

From 1964 to 1985, Brazilian citizens were tortured, raped and subjected to forced disappearances during the country’s military dictatorship. And in the decades since, most elements of the country’s democracy were restored, but the civilian-run government still has not gained back full control of Brazil’s security agencies. What’s more, while he was in office, Bolsonaro worked to make sure civilians did not regain that control by appointing thousands of military officers — both active duty and reserve — to civilian posts that controlled significant sectors of the government and the federal budget. He celebrated the 1964 coup that led to military rule and the military regime itself. And he made sure the military and police force were amply funded, giving the agencies a total of about US$5 billion by the end of his term. The country’s annual budget is about $19 billion.

The path to democracy

Restoring Brazil’s democracy and ridding the government of military influence may be Lula’s biggest challenge. But he’s taking practical steps to do it, such as firing a military general who reportedly prevented Jan. 8 rioters from being arrested. He also co-signed a letter with the governor of every state in Brazil, which explained that democracy is non-negotiable.

On a different front, Lula is combating rage with another powerful emotion: hope. The historian John French describes his approach as a “politics of cunning,” characterized by a willingness to compromise and a vision of the nation that feels more inclusive and equitable for all Brazilians.

When Lula was sworn in, he walked up the ramp to the Presidential Palace with eight representatives of his diverse political coalition, among them a metalworker, an Indigenous leader, a Black activist and a gay, disabled influencer.

This is a man who understands the power of symbols and is trying to change how Brazilians feel about their nation. He is asking them to claim a stake by embracing diversity — and democracy.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.