This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis. Versions of this article appeared at the Balkinization blog and at the Roosevelt Institute blog.

As we approach the so-called “x-date,” President Biden seems to be looking for a deal with congressional Republicans. Who has leverage in any such negotiation (now or in the future) depends very heavily on the question of what happens if there’s no deal. That is my subject in this post. Many journalists, pundits, and politicians seem to assume that if there is no deal, the President has only two options: default (stop paying some of the nation’s obligations) or else pursue the “Fourteenth Amendment option” — a way to “work around Congress” and keep paying the bills. But this way of looking at the problem has it backward. Default would thwart the will of Congress. Default would also violate the Fourteenth Amendment, which is not an “option,” but a bedrock of our constitutional order — it’s there whether anybody invokes it or not. The Biden administration has a constitutional duty to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” That means all the laws Congress has enacted, not just the debt-ceiling law.

Consider the statutory duties that Congress has imposed on the Biden Administration. I do not mean the political demands of the current House majority. I mean the actual statutes. Most pundits and politicians are focused on the debt-ceiling law as though it were the only law in play; it’s not. Congress passes a variety of statutes which require — not permit, but require — the president to spend money: payments to bondholders; payments to Social Security recipients (“mandatory spending”); annual appropriations, which means payments to defense contractors, federal employees, school districts, farmers, and so on down the line. President Biden doesn’t get to pick and choose about spending this money. He must spend what Congress has legislated in order to take care that those laws are faithfully executed. The beneficiaries of these expenditures have a statutory right to the funds and have accordingly ordered their affairs around receiving them: the school districts have hired the teachers, the federal employees have done their jobs every day, a defense contractor has built a nuclear submarine, and so on. They now have the right to the money the law says they’re owed. If Biden refuses to pay some of them today, that effectively creates IOUs for payments tomorrow. They’ll soon be in court to collect.

Meanwhile, separate from the spending statutes, Congress also passes statutes that raise revenue through taxes. And then finally, Congress in 1917 passed a third thing, a debt-ceiling statute (periodically updated) that gives the Treasury lots of discretion over how to borrow money but limits the total face value of the “obligations” (the debt) that the Treasury can borrow.

The so-called “x-date” is just when the conflict between these statutes becomes acute. Continuing to faithfully execute Congress’ mandates to spend money — which Biden is obligated by law to do — would seem to entail taking on more debt than Congress’ other command, the debt-ceiling statute, allows. The question is what the Biden administration should do at that point in the face of these conflicting statutory obligations. (Mike Dorf and Neil Buchanan explain all this in a pathbreaking article from 2012.)

Section 4 of the Fourteenth Amendment (“14.4”) says: “The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law . . . shall not be questioned.” Some have suggested that what President Biden should do on or about the x-date is simply declare that the debt-ceiling statute is unconstitutional under 14.4 and that he will therefore not follow it, and will borrow in excess of the limit. While this is a plausible approach, I do not think it is the best one, and more fundamentally it misunderstands the role of the Fourteenth Amendment in our story.

Rather than being an “option,” like some kind of magic card to pull from one’s hand and play in case of emergency, the Fourteenth Amendment’s strange and wonderful universal admonition that “The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law . . . shall not be questioned” looms over whatever choices the Biden administration makes. It looms equally large over Congress, where senators and representatives should — and undoubtedly will — cite it as justification for passing their preferred versions of the debt-ceiling extension. President Biden might cite 14.4 as justification for prioritizing some government obligations over others (which is an exceptionally bad idea). But even if 14.4 didn’t exist, the Biden administration is obligated to obey both the money-spending statutes and the debt-limit statute. Even absent 14.4, as Bob Hockett pointed out in a terrific op-ed, there are good reasons to think that the spending statute should have priority over the debt-limit statute when we apply ordinary principles of statutory construction, including the simple fact that the spending statutes are generally more recent in time.

But what if the Biden administration found a way to both spend the money Congress has required it to spend and avoid the need to raise the debt limit — a way to comply with all of Congress’ commands? There are several maneuvers that could potentially accomplish this. Any such maneuver will be challenged in court. But keep in mind: literally anything the Biden administration chooses to do if we reach the x-date — including doing nothing — will draw a chaotic flurry of lawsuits. And this is 2023, so we can assume that many such lawsuits will be of a deeply dysfunctional character (e.g. a nationwide injunction out of Amarillo, zooming to the Supreme Court on the shadow docket — that sort of thing). The Biden administration thus faces a complex legal and political optimization problem: how best to fulfill all its statutory and constitutional duties in a way that the courts, the markets, and the American public are most likely to accept?

The administration is unlikely to be able to try several things and see what works. They get one shot, right around the x-date, if Congress doesn’t manage to pass a debt-ceiling increase by then. Markets are likely to react with relief (relative to the prospect of a default), but that relief will be tempered by a concern that a court might undo the administration’s solution. Accordingly, the single most important risk to be minimized is the risk that litigation will result in a court order causing the U.S. to default. Minimize that risk successfully — through a method that is comprehensible to outside observers — and everyone, including in the financial markets, can breathe easier.

Of course, there are many reasons for a court to avoid ordering the Biden administration to default anyway. A careful, self-restrained court would be looking for ways not to issue such an order. Apart from its destructive effect on the national economy and on America’s creditworthiness, such an order would also have a destructive effect on the Supreme Court. There are ample jurisprudential means by which a court could avoid ordering a default, the most obvious being that nobody actually has standing to sue to force the government to default on its debts. (A court could also abstain on the grounds that default is a “political question,” etc.) The off-ramps for a court wishing to exercise restraint are plentiful. However, I expect that on an issue of such importance, the Supreme Court of 2023 has at least a fair likelihood of deciding to reach the merits. (In any case, markets would probably prefer a decision that reached the merits and unambiguously upheld the administration’s actions to a decision to avoid the merits and leaves the door open to additional litigation.)

Hopefully, the conversation about what to do on the x-date — and specifically about the different maneuvers I discuss below — is going on right now inside the Treasury Department. (Otherwise, we are all in huge trouble.) But it’s important for rest of us, outside the Treasury Department, to talk as well about how this might work, because that can help prepare the ground in our public discourse for the possibility that the administration will actually make one of these moves at that last minute and save the nation from default.

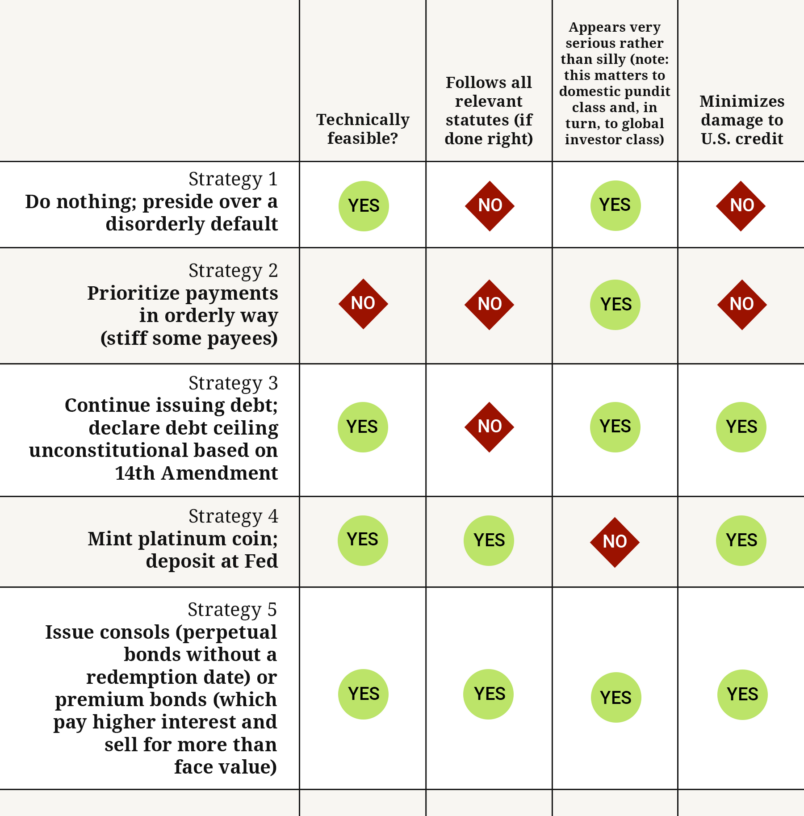

So what are these potential extraordinary maneuvers? I’ll discuss three. All are much more sound than either a chaotic default, or prioritizing some spending over other spending (which is just a more orderly form of default, and worse, involves taking political ownership of the austerity program). All of these maneuvers give a court good reasons to avoid ordering a default. But that does not make them equally likely to succeed.

The most famous of these ideas is for the Treasury to mint a platinum coin worth some very large amount of money, deposit it at the Fed, and use that money to pay the bills. This is basically a form of printing money. The amount of money the Treasury can print is generally restricted by statute, but the statutes allow a platinum coin of any amount. Legally, this approach is not immune from challenge. For example, some will argue that the statute really only allows commemorative coins, rather than coins that are real legal tender. In addition, this maneuver relies on Jerome Powell accepting the coin. There’s some uncertainty about how that would go. Still, overall, in my view the legal case for this option is solid. Its main problem is of a different kind: Much of the American punditocracy finds it silly. And unfortunately, the global investor class will listen to the domestic pundit class. Debt politics is about public confidence, and if people think you’re being silly, that can cause real harm to American credit. That is the chief shortcoming of this strategy.

The other two strategies rely on the Treasury issuing unusual types of bonds. Here the idea is to focus carefully on what the debt limit statute actually limits. It’s the “face amount of obligations,” 31 U.S. Code § 3101(b). So, what if the Treasury finds a way to raise lots of money from bond auctions but not increase the “face amount of obligations” outstanding? That’s the idea behind using consols or premium bonds.

Consols are “perpetual” bonds that never mature. They just pay a set rate of interest, really just a set stream of payments, in perpetuity. The face value and interest rate are up to the Treasury. If the face value is very low or zero, they would seem to add very little or zero to the debt for purposes of the debt limit statute. The U.S. has issued consols before and the Treasury has the authority to do so again. The other, slightly less exotic option is so-called “premium bonds”: bonds that have a maturity date like normal bonds, but that pay extra-high rates of interest — so that for example the Treasury might be able to sell a $500 bond paying lots of extra interest for the same amount they’d normally sell a $1,000 bond, but the face value, which is what the debt limit actually limits, could be much lower.

The debt limit statute has some additional clauses that sometimes cause “face value” to mean something other than its obvious meaning; to make sure none of those clauses applies to these new premium bonds or consols, the Treasury ought to make the bonds “redeemable before maturity at the option of the holder” (at their low face value only, without interest), and in addition, to be safe, the Treasury ought to be sure to sell the bonds not “on a discount basis” but instead for a premium well above their face value. (Do not worry, reader, that is as deep in the weeds as we’re going to get.)

The bottom line is that by carefully following the words of the statute, the Treasury Department can sell bonds, either to investors or to the Fed, that raise plenty of funds, but whose face value is very low. In that way, the government can stay in compliance with the debt limit as well as its spending obligations.

Because these maneuvers are new, there are limits to how far anyone can game out exactly how courts will react to them. But the government’s goal here is not to eliminate all legal uncertainty. The goal is to provide the Supreme Court with a simple, straightforward, textualist (I might even say Gorsuchian) way to uphold what Treasury has done, and rule that the government remains in compliance with the debt-ceiling law. To be sure, there may be some on the Supreme Court who are tempted to rule otherwise, to order the government to throw the nation into default. But the Biden administration can make that a very uphill legal road — and that is what these low-face-value bond sales accomplish.

Imagine the court decision actually ordering the United States to default. First, the Court would have to barrel through the barrier that no person actually has standing to demand that the United States stop paying people and entities what they’re owed. Second — and this is where the bond maneuver does its work — the Court would have to ignore the plain text of the debt-ceiling statute, which focuses on “face value,” in favor of some broader reading of the spirit and purpose of statute rather than its text. That is all fine and good, but keep in mind, the actual purpose of the debt limit statute, when enacted in 1917 during World War I, was to expand the power to borrow, not constrict it! So the Court would have to retcon a purpose and meaning onto the debt-ceiling statute that looks more like the austerity dreams of the present-day House Republicans.

Third, the Court would have to decide that the debt-limit statute trumps the other, more recent statutes passed by Congress that require the government to spend, to pay all the veterans, social security recipients, employees, contractors, and so on who are owed money by law. Why would anyone think that in a conflict between those statutes, it’s automatically the debt limit that wins? Indeed, it’s much worse than that. Ordering a default would mean ordering the Biden administration to pick and choose among its spending obligations, in a way that violates not only abstract separation-of-powers principles but also very clear Supreme Court precedents eliminating, in other contexts such as the line-item veto, the power of the executive to pick and choose among spending obligations set by Congress. The president doesn’t get to do that. But the Court would effectively be ordering the Biden administration to do it. And perversely, it wouldn’t even fix the problem: As Dorf and Buchanan showed in 2014, every unilateral spending cut actually adds to our “obligations” under the debt-limit statute. The IOUs that all those defense contractors, Social Security recipients, school districts, and so on are effectively accumulating as we fail to spend the money Congress appropriated are “obligations” that will later need to be paid — and that courts will enforce. They increase our overall obligations. To order a default, a court would have to pretend that these are not real obligations, that bondholders are the specially favored and that the United States’ many other creditors (everyone to whom we owe money at a given moment) do not count.

At the end of the day, the only real justification for ordering a default — for elevating the debt ceiling above other statutes, for blowing up the separation of powers regime on spending, for deciding that some obligations count and others don’t, and ultimately, for destroying the good credit of the United States — would be an underlying commitment on the part of the Court to a particular, fundamentally austerity-centered vision of constitutional political economy.

That is certainly the view of Kevin McCarthy and his caucus in the house. They may not agree on much, but they all seem to agree that the debt-limit statute, a statute originally enacted for the opposite purpose from the one to which it is now being put (it was enacted to make borrowing easier!), is some kind of super-statute that trumps the president’s obligation to take care to faithfully execute all the other laws that require spending money. The underlying reason the House Republicans believe this is because they want to build a constitutional political economy with a weakened federal government, hamstrung by restrictions that make it operate more like a business with a balance sheet and less like a democratic sovereign through which the people and their representatives can steer the nation’s economic development.

That is their constitutional vision. It is the key to making sense of why they assume the debt-ceiling statute trumps Congress’ other (and more recent) enactments that require the money to be spent. But there is no reason for the rest of us to adopt this deeply misguided and destructive vision of constitutional political economy. And there is every reason for the Biden administration to make it has hard as possible for a Court sympathetic to that vision to turn it into law.

If it turns out that we really are being ruled by a right-wing faction in robes that is determined to impose on us all an austerity-centered vision of constitutional political economy in which the debt-limit statute is transfigured into the pro-austerity super-statute of Kevin McCarthy’s dreams… well then at least make them do their own dirty work. Do not do their work for them. Strategies like “prioritizing payments” are doing their work for them. Instead, the administration should execute a low-face-value bond strategy that carefully complies with the letter of the law. This maneuver ought to give even this Supreme Court what it needs to step back from the brink.