This article is part of TPM Cafe, TPM’s home for opinion and news analysis.

The Munich agreement of 1938, in which Britain’s appeasement of Germany permitted the Nazi conquest of Eastern Europe, belongs on the list of well known no-go historical comparisons for its many abuses, including justification of the U.S. wars in Vietnam and Iraq. But now we need a corollary: if “Munich” should not be deployed to authorize military adventurism, neither should later, ill-advised wars reflect retroactively on the debate over whether the U.S. should have aided the fight against Hitler. If you find yourself arguing, “maybe the appeasers had a point,” you should stop. To borrow from dril, “you do not, under any circumstances, ‘gotta hand it to'” the America Firsters.

Russia’s war on Ukraine has revived the arguments of 1940–41. An aggressor invades a neighbor it regards as illegitimate, forcibly relocating its people and occupying its land. Sympathizing with the victims, Americans nevertheless would rather not fight a war. U.S. leaders, sensible of the analogy to the past, invoke the Franklin Roosevelt administration to justify aid short of war — most explicitly when, this May, President Biden signed a law styled the Ukraine Democracy Defense Lend-Lease Act.

The March 1941 Lend-Lease Act allowed the United States to supply first Britain, then the Soviet Union and other countries fighting fascism, without billing them. Roosevelt likened it to lending one’s neighbor a garden hose when his house is on fire; one does not ask payment, just the hose’s return once the fire is safely out. Under Lend-Lease, the United States sent tanks, airplanes, trucks, food, and fuel (among other goods) to nations seeking to extinguish the conflagration of fascist conquest. Churchill referred to Lend-Lease as “the most unsordid act in the whole of recorded history.” Stalin and Khrushchev both said it was essential to Allied victory and later histories support this view.

Observing the administration’s comparison between then and now, some scholars challenge the historical narrative, and in doing so have revived the arguments leveled against U.S. aid to the Allies in the early years of World War II. Adam Tooze, skeptical of the current Democratic leadership, urges historians to discard “the sugar-coated narrative of a ‘good war’ won by the ‘arsenal of democracy'” and understand the Lend-Lease law instead as a “dramatic act of escalation” in the conflict with Hitler. In adopting it, Tooze says, the U.S. was “crossing the point of no return” and “unleashing . . . an apocalyptic world war.”

From an opposite ideological position, the neoconservative Robert Kagan agrees, accepting arguments of self-proclaimed realists and other Roosevelt critics that “American security was not immediately or even prospectively threatened.” Thus, Kagan argues approvingly, U.S. intervention in World War II was unforced; it was a choice the Roosevelt administration made, hoping to impose liberal ideals on the world.

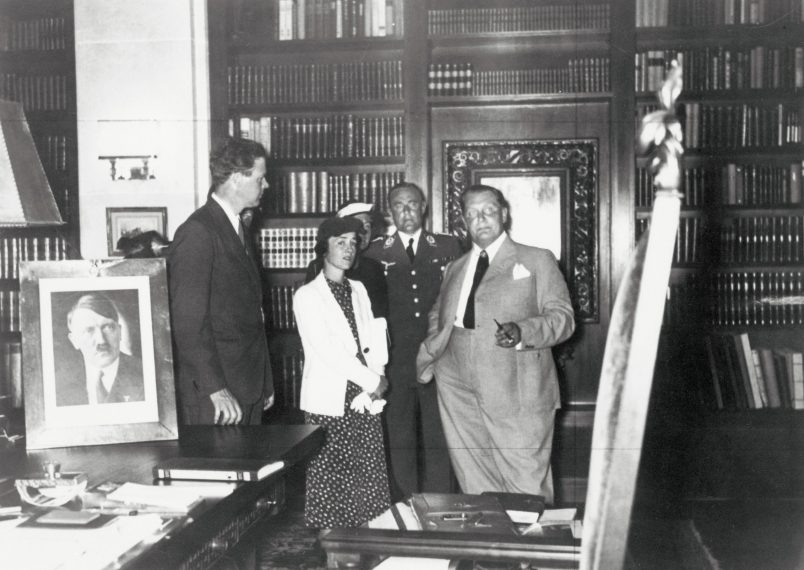

While similar arguments casting Lend-Lease as an unnecessary escalation were common in 1941, it is worth briefly noting that they were often made by people who were at least Nazi-curious, including many members of the America First movement. Charles Lindbergh kept a medal the Nazis gave him, though he resigned his U.S. Army commission; Anne Morrow Lindbergh was (as Kagan notes) a “best-selling author,” notably for a book in which she said “‘democracy’” (scare quotes hers) was done and fascism was “the wave of the future.” The America First Committee expunged well known anti-Semite Henry Ford but kept attracting people who thought the Nazis had a point — which to be fair was, for a long time, a mainstream U.S. position; in a 1938 poll 54 percent of respondents agreed that European Jews were partly to blame for their own persecution (eleven percent thought them entirely to blame). Some actual pacifists (like socialist Norman Thomas) opposed U.S. aid to the Allies, but they were few compared to nationalist critics whose pacifism was, as the historian Manfred Jonas writes, “ad hoc” — that is, not a pacifism of principles.

Setting these alarming associations momentarily aside: Tooze and Kagan — and anyone else arguing that America First was substantially correct — owe their readers an alternative history in which, absent U.S. aid to the Allies, Nazi ambitions find their limits. In 1939 and 1940, Germany had already — together with the USSR, then still Germany’s non-aggressor neighbor — divided eastern Europe. Then Germany conquered Norway and western Europe, and began bombing British airfields and cities. Fascist Italy waged war on Greece, which Germany would soon help defeat; likewise, German forces would aid Italy in North Africa, threatening capture of the Suez Canal and with it control of shipping to the East.

If not for Lend-Lease, Hitler would have found something else to propel him onward. Evidence is lacking that, absent U.S. aid to the Allies, Nazism would have limited itself.

In July 1940, Hitler ordered the construction of a surface fleet for war against the United States: as the historian Gerhard Weinberg writes, “nothing more clearly illuminates the world-wide ambitions of the Third Reich.” Hitler had long regarded the United States as a model to be imitated and a rival to be defeated and, as Brendan Simms and Charlie Laderman note, after January 1939, when Hitler outlined a global war that would mean “the destruction of the Jewish race in Europe,” he began planning war on the United States. “It was no longer a question of whether war with America would come,” Simms and Laderman write, “but when.”

Absent U.S. aid to the Allies, Germany might not have needed to build a fleet to attack the United States. It could have seized one. Churchill more than once reminded Roosevelt that if the Battle of Britain went badly, his government would fall. Appeasers would succeed him and in negotiating peace with Germany, “the sole remaining bargaining counter with Germany would be the fleet.” With the Royal Navy reflagged as the new Kriegsmarine, Hitler “might, of course, use it with a merciful moderation,” Churchill said. “On the other hand he might not.”

Churchill here forecast the fallacy underlying arguments rehabilitating America Firstism: that Hitler would, if unprovoked, show “a merciful moderation” from which he had, thus far, refrained. Instead Hitler cited a series of pretexts — some based on real events, some wholly invented — to advance the global race war he wanted. As Tooze notes, Hitler complained that Lend-Lease was an act of war — but a war that “was sure to come sooner or later anyway.” On that reading of history, the argument for Lend-Lease as escalation loses force: if not for Lend-Lease, Hitler would have found something else to propel him onward. Evidence is lacking that, absent U.S. aid to the Allies, Nazism would have limited itself.

Neither was Japan self-limiting in 1941. A Pacific policy of non-confrontation also failed. The U.S. imposed an oil embargo only after learning that, as historian R.J.C. Butow writes, “forbearance toward the government in Tokyo, instead of having a salutary effect, simply resulted in ever-more aggressive behavior.”

I leave as an exercise for the reader the probable fate of Europe’s Jews, and others whom the Nazis regarded as inferior, in any plausible alternative history in which Hitler was trusted to show merciful moderation.

Whatever may be true of today’s Lend-Lease, the 1941 version was less an escalation than a recognition of the path on which Hitler had already set the world — a recognition that U.S. voters had already registered. As the historian Andrew Johnstone notes, the 1940 election put the question of aid to the Allies to the electorate — whatever Republican Wendell Willkie’s personal views, he ran as the isolationist candidate, accusing Roosevelt of “arbitrary and dictatorial” action for supplying Britain with destroyers and, in full “just-asking-questions” mode, saying, “many of us have wondered if he is deliberately inciting us to war.” Voters told pollsters they would prefer Willkie if there were no war in Europe but, under actually prevailing circumstances, they preferred Roosevelt. They understood, perhaps better than some modern scholars, how to evaluate the likely alternative history, and made their decision accordingly.