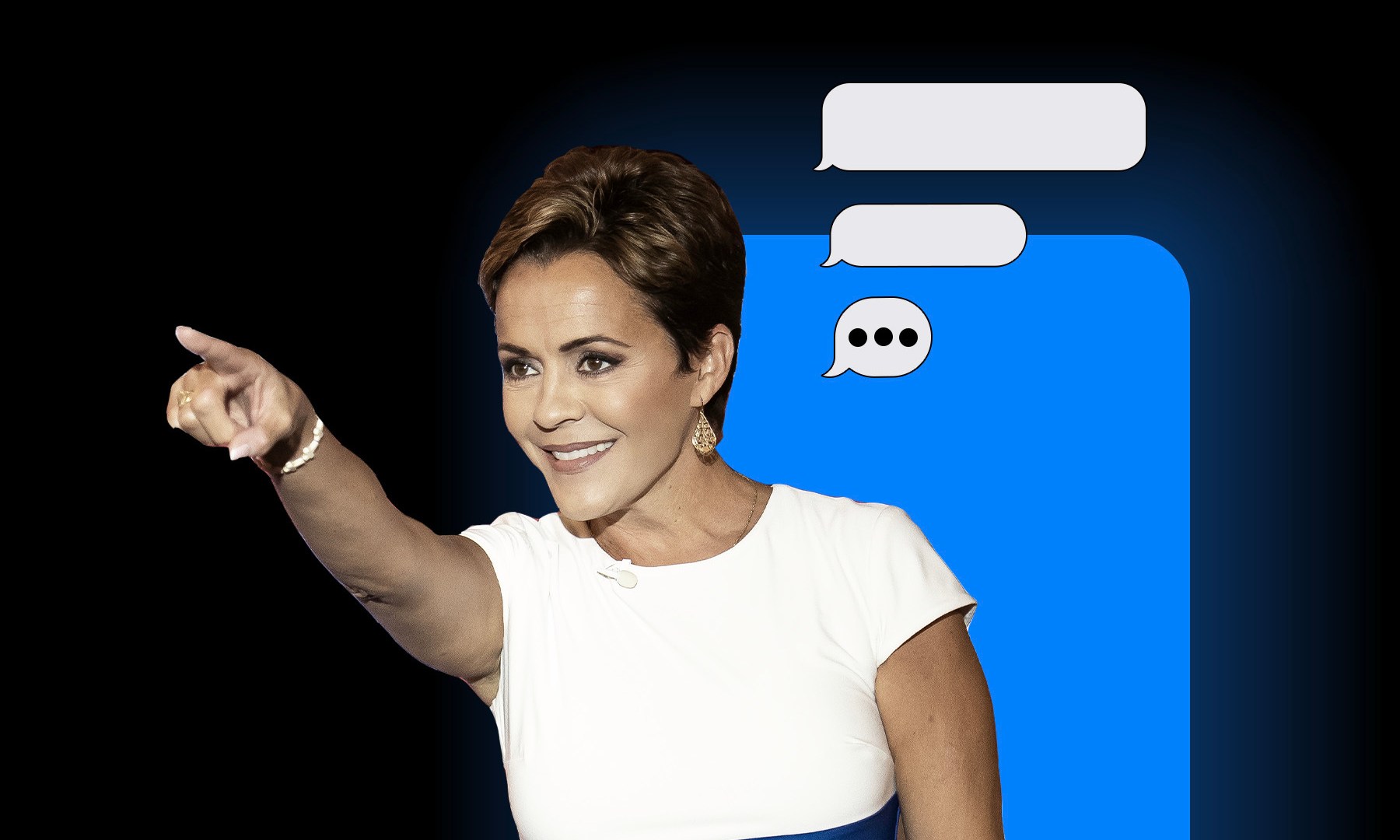

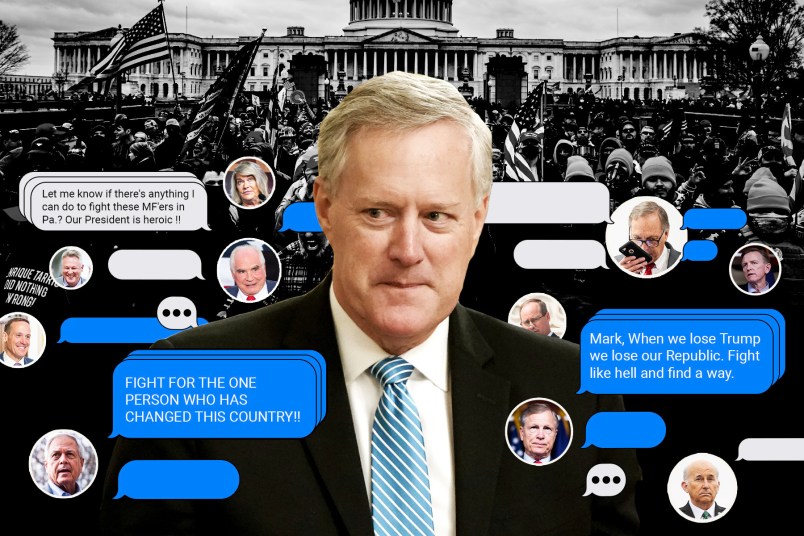

Failed Arizona gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake makes only one appearance in the 2,319 text messages former President Trump’s last chief of staff Mark Meadows provided to the House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack. However, Lake’s cameo provides an especially vivid example of how the challenge to Trump’s 2020 loss helped spur the creation of a new political movement that remains a force in American politics.

Lake is an election denier extraordinaire who is still engaged in a frivolous lawsuit to contest her loss nearly one month after that race was called. Before (publicly) jumping into politics, Lake had a longtime career as an anchor at KSAZ-TV, the local Fox affiliate in Phoenix. Lake was still in this position on November 7, 2020, when, based on the text log, Arizona Republican Party Chairwoman Kelli Ward texted Meadows with a hot tip that she said came from Lake.

11/7/20 4:20 p.m.

In other words, according to Ward, Lake, who had interviewed Trump, had come to the leader of the state’s Republican Party with information from a “source” that called into question the election result in Arizona, where Joe Biden won. Ward’s message came shortly after most of the major broadcast networks declared that Biden had won the presidency. Lake declined to comment on this story.

Lake may have felt her source was “credible” and this person may have genuinely been deathly afraid, but even in the short text, it is apparent their claims were absurd. States and even various local jurisdictions have different systems for counting votes and many of these are not connected to the internet at all. The idea there could be any method to use “modems” to affect voting in “all 50 states” is virtually impossible.

Ward, who did not respond to a request for comment, followed that text up with another one eight minutes later where she sent Meadows contact information for a man she described as “an attorney of 46 years in Florida and former military police in the army.”

“He’s credible,” Ward wrote.

TPM is not identifying the man because he is not a public figure. Reached via phone on Thursday, the man declined to comment about whether he communicated with Lake or if he believed modems had impacted the election nationally.

“I’m not going to make any comment,” the man said before hanging up.

Ward was intimately involved in the efforts to challenge the 2020 race. Ward fought a subpoena from the Jan. 6 committee for her phone logs from T-Mobile all the way to the Supreme Court, where she lost last month. She was also subpoenaed in June by a federal grand jury investigating Trump’s fake electors scheme. According to the log, Ward exchanged over 40 messages with Meadows. They include texts indicating Ward worked with Trump’s lawyer Rudy Giuliani and that she pressed local officials including Arizona’s Republican Gov. Doug Ducey about various challenges to the election.

The text log, which is not necessarily a complete record of Meadows’ communications, does not contain any response to Ward’s message about Lake’s “source.” For more information about the story behind the text log and our procedures for publishing the messages, read the introduction to this series. Meadows and the select committee did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

Lake’s personal politics have run the gamut over the years. For a profile that ran in October, the Washington Post spoke to friends and colleagues who described her as having been excited about Barack Obama and disillusioned with the forever wars in the Middle East. Between 2008 and 2012, Lake switched back and forth between the two parties. Her outlook steadily lurched to the right after Trump’s election in 2016, the Post reported.

In 2019, she got in trouble at work for cheerfully posting on Parler, an online hang for the far-right, which only intensified when she was caught on a hot mic discussing the kerfuffle and dismissing a local alt-weekly as a “rag for selling marijuana.” Last year, Lake left journalism to embark on a campaign built on looking backwards, fixating on the supposedly stolen 2020 election.

Lake’s television experience imbued her with the charisma that made so many either fear or admire her as a budding MAGAworld celebrity. But while her path to politics was unique, her final destination was not.

Based on a count from the Washington Post, Lake was one of 291 election deniers who ran for U.S. House, Senate or major statewide offices this cycle. Most, like Lake, were radicalized in 2020, when Trump infected the Republican Party with baseless doubts about the election’s validity. Many, like Lake, also lost: a big theme of this cycle was the widespread failure of the candidates who tried to win critical general elections on a Big Lie platform.

Nevertheless, Lake’s story provides a vivid example of how, for some, belief in 2020 conspiracies grew into efforts to enter the political realm. Even now, while she continues pursuing a case to get her loss overturned, Lake is staying active on social media, directing supporters to read her lawsuit on a website festooned with bright “donate” buttons in all caps.

“If they thought we would just sulk and accept the results of a rigged, sham election, they were wrong,” Lake said in a typically glossy, direct-to-camera address this week. “My resolve to fight for the millions of Arizonans disgusted with years of botched elections is stronger than ever.”